Citing Sources: Citing Orally in Speeches

- Citing Sources Overview

- Citing in the Sciences & Engineering

- APA Citation Examples

- Chicago Citation Examples

- Biologists: Council of Science Editors (CSE) Examples

- MLA Citation Examples

- Bluebook - Legal Citation

Citing Orally in Speeches

- Citation Managers

- Oral Source Citations - James Madison University Communication Center

- Using Citations and Avoiding Plagiarism in Oral Presentations - Hamilton College, Dept. of Rhetoric and Communication

- Referencing: Citing in Orals - James Cook University

General Tips:

Tell the audience your source before you use the information (the opposite of in-text citations).

Do not say, “quote, unquote” when you offer a direct quotation. Use brief pauses instead.

Provide enough information about each source so that your audience could, with a little effort, find them. This should include the author(s) name, a brief explanation of their credentials, the title of the work, and publication date.

“In the 1979 edition of The Elements of Style, renowned grammarians and composition stylists Strunk and White encourage writers to ‘make every word tell.’”

If your source is unknown to your audience, provide enough information about your source for the audience to perceive them as credible. Typically we provide this credentialing of the source by stating the source’s qualifications to discuss the topic.

“Dr. Derek Bok, the President Emeritus of Harvard University and the author of The Politics of Happiness argues that the American government should design policies to enhance the happiness of its citizens.”

Provide a caption citation for all direct quotations and /or relevant images on your PowerPoint slides.

Direct Quotations:

These should be acknowledged in your speech or presentation either as “And I quote…” or “As [the source] put it…”

Include title and author: “According to April Jones, author of Readings on Gender…”

Periodical/Magazine:

Include title and date: “Time, March 28, 2005, explains…” or “The New York Times, June 5, 2006, explained it this way…”

Include journal title, date, and author: “Morgan Smith writes in the Fall 2005 issue of Science…”

For organizational or long-standing website, include title: “The center for Disease Control web site includes information…” For news or magazine websites, include title and date: “CNN.com, on March 28, 2005, states…” (Note: CNN is an exception to the “don’t use the address” rule because the site is known by that name.)

Interviews, lecture notes, or personal communication:

Include name and credentials of source: “Alice Smith, professor of Economics at USM, had this to say about the growth plan…” or “According to junior Speech Communication major, Susan Wallace…”

- << Previous: Bluebook - Legal Citation

- Next: Citation Managers >>

- Last Updated: Sep 3, 2024 4:01 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wpi.edu/citingsources

How can we help?

- [email protected]

- Consultation

- 508-831-5410

Module 2: Ethical Speech

Citing sources in a speech, learning objectives.

Explain how to cite sources in written and oral speech materials.

Tips on citing sources when speaking publicly by Sarah Stone Watt, Pepperdine University

Even if you have handed your professor a written outline of your speech with source citations, you must also offer oral attribution for ideas that are not your own (see Table below for examples of ways to cite sources while you are speaking). Omitting the oral attribution from the speech leads the audience, who is not holding a written version, to believe that the words are your own. Be sure to offer citations and oral attributions for all material that you have taken from someone else, including paraphrases or summaries of their ideas. When in doubt, remember to “always provide oral citations for direct quotations, paraphrased material, or especially striking language, letting listeners know who said the words, where, and when.” [1] Whether plagiarism is intentional or not, it is unethical, and someone committing plagiarism will often be sanctioned based on their institution’s code of conduct.

|

|

|

| “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life” (Jobs, 2005). | In his 2005 commencement address at Stanford University Steve Jobs said, “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life.” |

| “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants” (Pollan, 2009, p.1). | Michael Pollan offers three basics guidelines for healthy eating in his book, . He advises readers to “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” |

| “The Assad regime’s escalating violence in Syria is an affront to the international community, a threat to regional security, and a grave violation of human rights. . . . [T]his group should take concrete action along three lines: provide emergency humanitarian relief, ratchet up pressure on the regime, and prepare for a democratic transition” (Clinton, 2012). | In her February 24 speech to the Friends of Syria People meeting, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned that Assad was increasing violence against the Syrian people and violating human rights. She called for international action to help the Syrian people through humanitarian assistance, political pressure, and support for a future democratic government. |

| “Maybe you could be a mayor or a Senator or a Supreme Court Justice, but you might not know that until you join student government or the debate team” (Obama, 2009). | In his 2009 “Back to School” speech, President Obama encouraged students to participate in school activities like student government and debate in order to try out the skills necessary for a leadership position in the government. |

In your speech, make reference to the quality and credibility of your sources. Identifying the qualifications for a source, or explaining that their ideas have been used by many other credible sources, will enhance the strength of your speech. For example, if you are giving a speech about the benefits of sleep, citing a renowned sleep expert will strengthen your argument. If you can then explain that this person’s work has been repeatedly tested and affirmed by later studies, your argument will appear even stronger. On the other hand, if you simply offer the name of your source without any explanation of who that person is or why they ought to be believed, your argument is suspect. To offer this kind of information without disrupting the flow of your speech, you might say something like:

Mary Carskadon, director of the Chronobiology/Sleep Research Laboratory at Bradley Hospital in Rhode Island and professor at the Brown University School of Medicine, explains that there are several advantages to increased amounts of sleep. Her work is supported by other researchers, like Dr. Kyla Wahlstrom at the University of Minnesota, whose study demonstrated that delaying school start times increased student sleep and their performance (National Sleep Foundation, 2011).

This sample citation bolsters credibility by offering qualifications and identifying multiple experts who agree on this issue.

- Turner, Kathleen J., et al. Public Speaking . Pearson, 2017. ↵

- Jobs, S. (2005, June 14). "You've got to find what you love," Jobs says. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from http://news.stanford.edu/news/2005/june15/jobs-061505.html ↵

- Tips on citing sources. Authored by : Sarah Stone Watt. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/supporting.html . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives . License Terms : Used with Permission

Holman Library

- GRC Holman Library

- Green River LibGuides

- Library Instruction

Research Guide: Citations

- APA Verbal/Speech Citations Example

- Citing Sources

- Quick Overview

- Plagiarism & Academic Honesty This link opens in a new window

- APA Citation Style Overview

- In-Text Citations - APA

- ARTICLES - APA Reference List

- BOOKS - APA Reference List

- ONLINE SOURCES - APA Reference List

- OTHER SOURCES - APA Reference List

- APA Formatted Paper Example

- APA Annotated Bibliography Example

- APA Images and Visual Presentations Citations Example

- MLA Citation Style Overview

- In-Text Citations - MLA

- ARTICLES - MLA Works Cited

- BOOKS - MLA Works Cited

- ONLINE SOURCES - MLA Works Cited

- OTHER SOURCES - MLA Works Cited

- MLA Formatted Paper Example

- MLA Annotated Bibliography Example

- MLA Verbal/Speech Citation Example

- MLA Images and Visual Presentations Citations Example

- Other Citation Styles

- Citation Generator (NoodleTools)

- Synthesizing Sources

- Get Help & Citation Workshops

Verbal Citations in Speeches and Presentations

What should you include in a verbal citation, when you give a speech....

(click on image to enlarge)

Why cite sources verbally?

- to c onvince your audience that you are a credible speaker. Building on the work of others lends authority to your presentation

- to prove that your information comes from solid, reliable sources that your audience can trust.

- to give credit to others for their ideas, data, images (even on PowerPoint slides), and words to avoid plagiarism.

- to leave a path for your audience so they can locate your sources.

What are tips for effective verbal citations?

When citing books:

- Ineffective : “ Margaret Brownwell writes in her book Dieting Sensibly that fad diets telling you ‘eat all you want’ are dangerous and misguided.” (Although the speaker cites and author and book title, who is Margaret Brownwell? No information is presented to establish her authority on the topic.)

- Better : “Margaret Brownwell, professor of nutrition at the Univeristy of New Mexico , writes in her book, Dieting Sensibly, that …” (The author’s credentials are clearly described.)

When citing Magazine, Journal, or Newspaper articles

- Ineffective : “An article titled ‘Biofuels Boom’ from the ProQuest database notes that midwestern energy companies are building new factories to convert corn to ethanol.” (Although ProQuest is the database tool used to retrieve the information, the name of the newspaper or journal and publication date should be cited as the source.)

- Better : “An article titled ‘Biofuels Boom’ in a September 2010 issue of Journal of Environment and Development” notes that midwestern energy companies…” (Name and date of the source provides credibility and currency of the information as well as giving the audience better information to track down the source.)

When citing websites

- Ineffective : “According to generationrescue.org, possible recovery from autism includes dietary interventions.” (No indication of the credibility or sponsoring organization or author of the website is given)

- Better : “According to pediatrician Jerry Kartzinel, consultant for generationrescue.org, an organization that provides information about autism treatment options, possibly recovery from autism includes dietary interventions.” (author and purpose of the website is clearly stated.)

Note: some of the above examples are quoted from: Metcalfe, Sheldon. Building a Speech. 7th ed. Boston: Wadsworth, 2010. Google Books. Web. 17 Mar. 2012.

Video: Oral Citations

Source: "Oral Citations" by COMMpadres Media , is licensed under a Standard YouTube License.

Example of a Verbal Citation

Example of a verbal citation from a CMST 238 class at Green River College, Auburn, WA, February 2019

What to Include in a Verbal Citation

- << Previous: APA Annotated Bibliography Example

- Next: APA Images and Visual Presentations Citations Example >>

- Last Updated: Aug 14, 2024 4:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.greenriver.edu/citations

Subject Guide: Communication: Citing Sources Orally

- Background Information & Reference Books

- Developing a Research Question

- Defining Scholarly Sources

- Using OneSearch

- Research Strategies: How to "Speak" Database

- Communication Journals

- Finding Empirical Sources

- Finding Biographical Articles

- Finding Biographical Books

- Contemporary Issues

- Evaluating Sources

- Citing Sources Orally

What Are Oral Citations?

Oral citations : When you are delivering your speeches, you should plan on telling the audience the source(s) of your information while you are speaking. (from James Madison University Communication Center )

A good speech should be well-researched, and many times you will be using facts, statistics, quotes, or opinions from others throughout. If you do not cite your sources orally, this can be considered plagiarism and is unethical. This applies to direct quotations, paraphrasing, and summarizing. You must orally cite, even if you will be providing a bibliography, works cited, or reference list to your instructor. (adapted from Sante Fe College Oral Citation LibGuide )

Why Cite Your Sources During a Speech?

(adapted from College of Southern Nevada's Oral Citation LibGuide )

CREDIBILITY

An oral citation conveys the reliability, validity and currency of your information. Citing your sources orally lets your audience know that you have researched your topic. The stronger your sources are, the stronger your credibility will be.

Bakersfield College’s Student Academic Integrity Policy defines plagiarism as “ the act of using the ideas or work of another person or persons as if they were one's own, without giving credit to the source.” This policy, along with Bakersfield College’s Student Code of Conduct, Code #15 , prohibit plagiarism.

Failure to provide an oral citation is considered a form of plagiarism, even if you cite your sources in a written outline, bibliography, works cited page or list of references.

When you are delivering a speech, you must provide an oral citation for any words, information or ideas that are not your own.

When Do You Cite Sources in a Speech?

(adapted from Gateway Community and Technical College COM 181 LibGuide )

- Oral citations will always be in a narrative style; you mention citation details about the work as part of your presentation.

- Place the citation before the information to give weight and authority to what you're about to say.

- You must cite words or ideas that come from another person or you will be plagiarizing their work!

- When you are providing information that is not commonly known, such as statistics, expert opinions, or study results.

- Whenever you use a direct quotation.

- If you are unsure if a citation is required, be safe and cite the source.

Citing Sources in a Speech Video

How Do You Cite Sources in a Speech?

The best practice is to provide a full oral citation that would include the author(s) (assuming that is available), the name of the publication, the specific publication date and year, and any other pertinent information. How you cite your information should highlight the most important aspects of that citation (e.g., we may not know who “Dr. Smith” is, but if Dr. Smith is identified as a lead researcher of race relations at New York University, the citation will take on more credibility). (adapted from Tips for Oral Citations from Eastern Illinois University )

(adapted from Gateway Community and Technical College COM 181 LibGuide )

The first mention of a work should include all citation elements; subsequent mentions of that work only require the author as long as source attribution remains clear (i.e. you have not used a different source in intervening narrative).

What are the elements of an oral citation.

- If the source might not be recognized by your listeners, add a comment to help establish its credibility.

- Include enough detail to help your listener locate the work later.

- Do give the full date in citations that refer to newspaper or magazine articles.

- Particularly important if there are statistics or data that change over time.

- Mention the publication year for books and journals.

- If there is there is no date, as with some websites, state the date that you accessed the material.

- Also indicate the Author's credentials (why they are an authority on the subject).

- If there are two authors, use both names in your citation.

- If there are more than two authors, name the first author and use "and associates" or "and colleagues".

- If the full title is long, use a shortened version that makes sense and still communicates enough information for your listener to locate the work.

How do I orally cite a quotation?

- You should make in clear that you are directly quoting another person rather than paraphrasing or summarizing their work. You can use a signal phrase like "... and I quote" or "As Jonas said..." to introduce the cited material.

Examples of Oral Citations in a Speech

(adapted from Tips for Oral Citations from Eastern Illinois University )

For a magazine article

“According to an article by Ben Elgin in the February 20th, 2006 issue of Business Week, we can expect Google and Yahoo’s supremacy as the search engine giants to be challenged by new U.S. startups. Elgin reports that …”

“As reported in the February 20th, 2006 issue of Business Week, many new companies are getting into the search engine business. This article explains that …”

“A February 20th, 2006 Business Week article reported that Google and Yahoo will face stiff competition in the search engine business …”

For a newspaper article

“On February 22nd, 2006, USA Today reported that …”

“An article about the effects of global warming appeared in the February 22nd edition of USA Today. Todd Smith’s report focused on the alarming rate of …”

“An article on global warming that appeared in the February 22nd issue of USA Today sounded the alarm …”

For a website

“On January 12. 2019, I visited the “Earthquakes” page of www.ready.gov , the website of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. businesses and citizens …”

“According to the Earthquakes page on U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s website, …”

“Helpful information about business continuity planning can be found on the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s website, located at www.ready.gov …”

“On January 12, 2019, I consulted the website maintained by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to learn more about what businesses should do to plan for an emergency. In the section entitled ‘Plan to stay in business,’ several recommendations for maintaining continuity of business operations were offered. These suggestions included …”

For a journal article

“A study published on December 12, 2004, in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology reported that incidents of workplace aggression have increased …”

“Research conducted by Dr. Bailey and Dr. Cross at Stanford University found that incidents of workplace aggression have increased over the past five years. Their 2004 study published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology in December of that year reported that …”

“According to a December, 2004 study published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, …”

“A December 2004 study by Bailey and Cross in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, …”

“In a December, 2004 study published in Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Bailey and Cross reported that …”

“A December 2004 study by Stanford University researchers found that incidents of workplace aggression …”

“Bailey and Cross, experts in workplace aggression, authored a study that shows that incidents of aggression in the workplace are increasing. Their December 2004 Journal of Applied Social Psychology article reports that …”

“In her 2005 book, Good Health at Any Age, Dr. Gabriella Campos describes how we can maintain our health through healthy eating. She recommends …”

“Gabriella Campos, an expert in nutrition, describes what is needed to maintain a healthy diet in her 2005 book Good Health at Any Age. She contends that …”

“In her recent book, Good Health at Any Age, Dr. Gabriella Campos recommends …”

“In Good Health at Any Age, Dr. Gabriella Campos, an expert in nutrition, offers suggestions for …”

For a television program

“On February 21, 2021, our local PBS station aired a program called “The Insurgency.” In this program …”

“According to “The Insurgency,” a Frontline program aired by PBS on February 21st,2021 ….”

- “Frontline, a PBS program, focused on the Iraq War in the television program entitled “The Insurgency.” This show aired on February 21, 2021, and focused on the problems confronting …”

For a YouTube video

“The Children and Young People’s Well-being Service, a branch of the UK National Health Service, uploaded Getting a Good Night’s Sleep–Top Tips for Teens to Youtube on January 7, 2021. In the video, they explain that caffeine is a stimulant and we will get better sleep if we avoid it for at least 6 hours before bedtime.”

“Nemours Foundation is non-profit organization established in 1936,dedicated to improving children’s health. In their How to help your teens get enough sleep video, uploaded to Youtube on July 6, 2022 they explain that teens’ body clocks change during puberty and teens naturally fall asleep later at night, which often leads to sleep depravation.”

For a personal interview

“On February 20th I conducted a personal interview with Dr. Desiree Ortez, a psychology professor here at Eastern, to learn more about student responses to peer pressure. Dr. Ortez told me that …”

“I conducted an interview with Dr. Desiree Ortez, a psychology professor at Eastern Illinois University, and learned that peer pressure is a big problem for university students.”

“In an interview, I conducted with Dr. Desiree Ortez, a psychology professor, I learned that …”

“I met with Dr. Desiree Ortez, a psychology professor here at Eastern, to learn more about … She told me that peer pressure is a major factor contributing to academic failure in college.”

“In a telephone interview I conducted with Dr. Forest Wiley, a gerontology professor at University of Illinois, I learned that the elderly are likely to feel ...”

“I emailed Dr. Forest Wiley, a gerontology professor at the University of Illinois, to get additional information on his research on the aging’s use of the Internet. He told me …”

- << Previous: Citing Sources

- Last Updated: Aug 27, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://bakersfieldcollege.libguides.com/Communications

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.3 Citing Sources

Learning objectives.

- Understand what style is.

- Know which academic disciplines you are more likely to use, American Psychological Association (APA) versus Modern Language Association (MLA) style.

- Cite sources using the sixth edition of the American Psychological Association’s Style Manual.

- Cite sources using the seventh edition of the Modern Language Association’s Style Manual.

- Explain the steps for citing sources within a speech.

- Differentiate between direct quotations and paraphrases of information within a speech.

- Understand how to use sources ethically in a speech.

- Explain twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism.

Quinn Dombrowski – Bilbiography – CC BY-SA 2.0.

By this point you’re probably exhausted after looking at countless sources, but there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done. Most public speaking teachers will require you to turn in either a bibliography or a reference page with your speeches. In this section, we’re going to explore how to properly cite your sources for a Modern Language Association (MLA) list of works cited or an American Psychological Association (APA) reference list. We’re also going to discuss plagiarism and how to avoid it.

Why Citing Is Important

Citing is important because it enables readers to see where you found information cited within a speech, article, or book. Furthermore, not citing information properly is considered plagiarism, so ethically we want to make sure that we give credit to the authors we use in a speech. While there are numerous citation styles to choose from, the two most common style choices for public speaking are APA and MLA.

APA versus MLA Source Citations

Style refers to those components or features of a literary composition or oral presentation that have to do with the form of expression rather than the content expressed (e.g., language, punctuation, parenthetical citations, and endnotes). The APA and the MLA have created the two most commonly used style guides in academia today. Generally speaking, scholars in the various social science fields (e.g., psychology, human communication, business) are more likely to use APA style , and scholars in the various humanities fields (e.g., English, philosophy, rhetoric) are more likely to use MLA style . The two styles are quite different from each other, so learning them does take time.

APA Citations

The first common reference style your teacher may ask for is APA. As of July 2009, the American Psychological Association published the sixth edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association ( http://www.apastyle.org ) (American Psychological Association, 2010). The sixth edition provides considerable guidance on working with and citing Internet sources. Table 7.4 “APA Sixth Edition Citations” provides a list of common citation examples that you may need for your speech.

Table 7.4 APA Sixth Edition Citations

| Research Article in a Journal—One Author | Harmon, M. D. (2006). Affluenza: A world values test. , 119–130. doi: 10.1177/1748048506062228 |

| Research Article in a Journal—Two to Five Authors | Hoffner, C., & Levine, K. J. (2005). Enjoyment of mediated fright and violence: A meta-analysis. , 207–237. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0702_5 |

| Book | Eysenck, H. J. (1982). New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. |

| Book with 6 or More Authors | Huston, A. C., Donnerstein, E., Fairchild, H., Feshbach, N. D., Katz, P. A., Murray, J. P.,…Zuckerman, D. (1992). . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. |

| Chapter in an Edited Book | Tamobrini, R. (1991). Responding to horror: Determinants of exposure and appeal. In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (Eds.), (pp. 305–329). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. |

| Newspaper Article | Thomason, D. (2010, March 31). Dry weather leads to burn ban. , p. A1. |

| Magazine Article | Finney, J. (2010, March–April). The new “new deal”: How to communicate a changed employee value proposition to a skeptical audience—and realign employees within the organization. (2), 27–30. |

| Preprint Version of an Article | Laudel, G., & Gläser, J. (in press). Tensions between evaluations and communication practices. Retrieved from |

| Blog | Wrench, J. S. (2009, June 3). AMA’s managerial competency model [Web log post]. Retrieved from |

| Wikipedia | Organizational Communication. (2009, July 11). [Wiki entry]. Retrieved from |

| Vlog | Wrench, J. S. (2009, May 15). Instructional communication [Video file]. Retrieved from |

| Discussion Board | Wrench, J. S. (2009, May 21). NCA’s i-tunes project [Online forum comment]. Retrieved from |

| E-mail List | McAllister, M. (2009, June 19). New listserv: Critical approaches to ads/consumer culture & media studies [Electronic mailing list message]. Retrieved from |

| Podcast | Wrench, J. S. (Producer). (2009, July 9). [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from |

| Electronic-Only Book | Richmond, V. P., Wrench, J. S., & Gorham, J. (2009). (3rd ed.). Retrieved from |

| Electronic-Only Journal Article | Molyneaux, H., O’Donnell, S., Gibson, K., & Singer, J. (2008). Exploring the gender divide on YouTube: An analysis of the creation and reception of vlogs. (1). Retrieved from |

| Electronic Version of a Printed Book | Wood, A. F., & Smith, M. J. (2004). (2nd ed.). Retrieved from |

| Online Magazine | Levine, T. (2009, June). To catch a liar. (3). Retrieved from |

| Online Newspaper | Clifford, S. (2009, June 1). Online, “a reason to keep going.” . Retrieved from |

| Entry in an Online Reference Work | Viswanth, K. (2008). Health communication. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), . Retrieved from . doi: 10.1111/b.9781405131995.2008.x |

| Entry in an Online Reference Work, No Author | Communication. (n.d.). In (9th ed.). Retrieved from |

| E-Reader Device | Lutgen-Sandvik, P., & Davenport Sypher, B. (2009). . [Kindle version]. Retrieved from |

MLA Citations

The second common reference style your teacher may ask for is MLA. In March 2009, the Modern Language Association published the seventh edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (Modern Language Association, 2009) ( http://www.mla.org/style ). The seventh edition provides considerable guidance for citing online sources and new media such as graphic narratives. Table 7.5 “MLA Seventh Edition Citations” provides a list of common citations you may need for your speech.

Table 7.5 MLA Seventh Edition Citations

| Research Article in a Journal—One Author | Harmon, Mark D. “Affluenza: A World Values Test.” 68 (2006): 119–130. Print. |

| Research Article in a Journal—Two to Four Authors | Hoffner, Cynthia A., and Kenneth J. Levine, “Enjoyment of Mediated Fright and Violence: A Meta-analysis.” 7 (2005): 207–237. Print. |

| Book | Eysenck, Hans J. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1982. Print. |

| Book with Four or More Authors | Huston, Aletha C., et al., . Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska P, 1992. Print. |

| Chapter in an Edited Book | Tamobrini, Ron. “Responding to Horror: Determinants of Exposure and Appeal.” Eds. Jennings Bryant and Dolf Zillman. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1991. 305–329. Print. |

| Newspaper Article | Thomason, Dan. “Dry Weather Leads to Burn Ban.” 31 Mar. 2010: A1. Print. |

| Magazine Article | Finney, John. “The New ‘New Deal’: How to Communicate a Changed Employee Value Proposition to a Skeptical Audience—And Realign Employees Within the Organization.” Mar.–Apr. 2010: 27–30. Print. |

| Preprint Version of an Article | Website. 15 July 2009. Pre-print version of Laudel, Grit and Gläser, Joken. “Tensions Between Evaluations and Communication Practices.” |

| Blog | Wrench, Jason S. “ AMA’s Managerial Competency Model.” . workplacelearning.info/blog, 3 Jun. 2009. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Wikipedia | “Organizational Communication.” . Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Vlog | Wrench, Jason S. “Instructional Communication.” . LearningJournal.com, 15 May 2009. Web. 1 Aug. 2009. |

| Discussion Board | Wrench, Jason S. “NCA’s i-Tunes Project.” . Web. 1 August 2009. |

| E-mail List | McAllister, Matt. “New Listerv: Critical Approaches to Ads/Consumer Culture & Media Studies.” Online posting. 19 June 2009. CRTNet. Web. 1 August 2009. 〈[email protected]〉 |

| Podcast | “Workplace Bullying.” Narr. Wrench, Jason S. and P. Lutgen-Sandvik. CommuniCast.info, 9 July 2009. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Electronic-Only Book | Richmond, Virginia P., Jason S. Wrench, and Joan Gorham. . 3rd ed. . Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Electronic-Only Journal Article | Molyneaux, Heather, Susan O’Donnell, Kerri Gibson, and Janice Singer. “Exploring the Gender Divide on YouTube: An Analysis of the Creation and Reception of Vlogs.” 10.1 (2008): n.pag. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Electronic Version of a Printed Book | Wood, Andrew F., and Matthew. J. Smith. 2nd ed. 2005. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Online Magazine | Levine, Timothy. “To Catch a Liar.” . N.p. June 2009. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Online Newspaper | Clifford, Stephanie. “Online, ‘A Reason to Keep Going.’” . 1 Jun. 2009. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Entry in an Online Reference Work | Viswanth, K. “Health Communication.” . 2008. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| Entry in an Online Reference Work, No Author | “Communication.” . 9th ed. 2009. Web. 31 Mar. 2010. |

| E-Reader Device | Lutgen-Sandvik, Pamela, and Beverly Davenport Sypher. . New York: Routledge, 2009. Kindle. |

Citing Sources in a Speech

Once you have decided what sources best help you explain important terms and ideas in your speech or help you build your arguments, it’s time to place them into your speech. In this section, we’re going to quickly talk about using your research effectively within your speeches. Citing sources within a speech is a three-step process: set up the citation, give the citation, and explain the citation.

First, you want to set up your audience for the citation. The setup is one or two sentences that are general statements that lead to the specific information you are going to discuss from your source. Here’s an example: “Workplace bullying is becoming an increasing problem for US organizations.” Notice that this statement doesn’t provide a specific citation yet, but the statement introduces the basic topic.

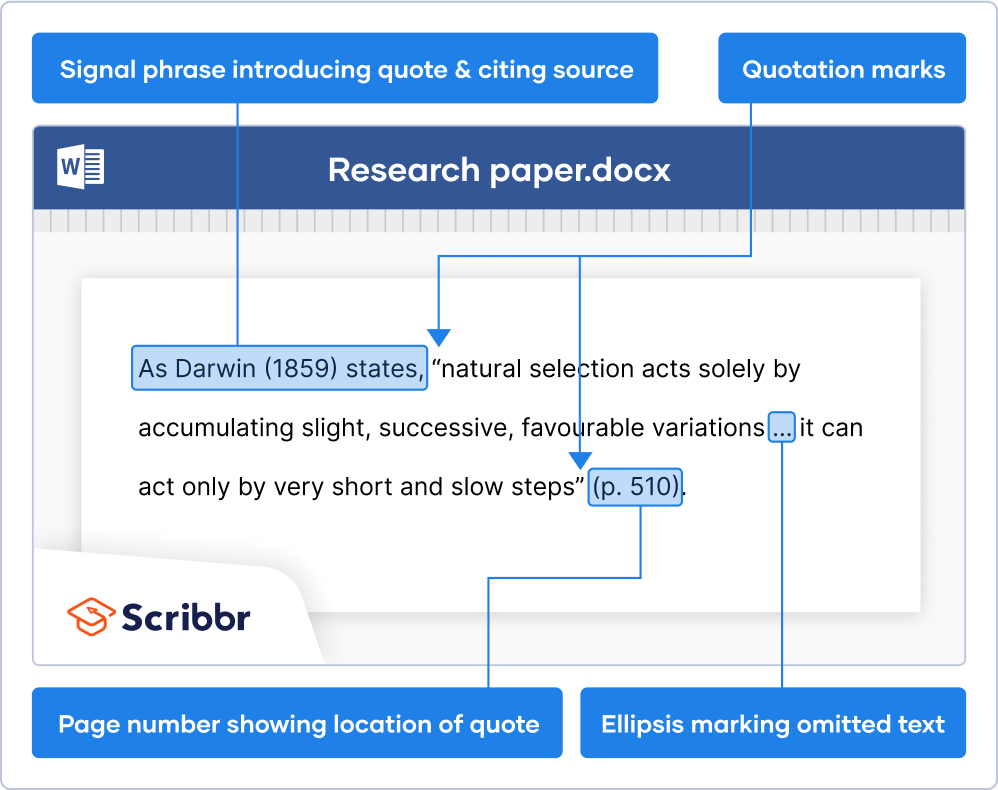

Second, you want to deliver the source; whether it is a direct quotation or a paraphrase of information from a source doesn’t matter at this point. A direct quotation is when you cite the actual words from a source with no changes. To paraphrase is to take a source’s basic idea and condense it using your own words. Here’s an example of both:

| Direct Quotation | In a 2009 report titled , the Workplace Bullying Institute wrote, “Doing nothing to the bully (ensuring impunity) was the most common employer tactic (54%).” |

| Paraphrase | According to a 2009 study by the Workplace Bullying Institute titled , when employees reported bullying, 54 percent of employers did nothing at all. |

You’ll notice that in both of these cases, we started by citing the author of the study—in this case, the Workplace Bullying Institute. We then provided the title of the study. You could also provide the name of the article, book, podcast, movie, or other source. In the direct quotation example, we took information right from the report. In the second example, we summarized the same information (Workplace Bullying Institute, 2009).

Let’s look at another example of direct quotations and paraphrases, this time using a person, rather than an institution, as the author.

| Direct Quotation | In her book , Mary George, senior reference librarian at Princeton University’s library, defines insight as something that “occurs at an unpredictable point in the research process and leads to the formulation of a thesis statement and argument. Also called an ‘Aha’ moment or focus.” |

| Paraphrase | In her book , Mary George, senior reference librarian at Princeton University’s library, tells us that insight is likely to come unexpectedly during the research process; it will be an “aha!” moment when we suddenly have a clear vision of the point we want to make. |

Notice that the same basic pattern for citing sources was followed in both cases.

The final step in correct source citation within a speech is the explanation. One of the biggest mistakes of novice public speakers (and research writers) is that they include a source citation and then do nothing with the citation at all. Instead, take the time to explain the quotation or paraphrase to put into the context of your speech. Do not let your audience draw their own conclusions about the quotation or paraphrase. Instead, help them make the connections you want them to make. Here are two examples using the examples above:

| Bullying Example | Clearly, organizations need to be held accountable for investigating bullying allegations. If organizations will not voluntarily improve their handling of this problem, the legal system may be required to step in and enforce sanctions for bullying, much as it has done with sexual harassment. |

| Aha! Example | As many of us know, reaching that “aha!” moment does not always come quickly, but there are definitely some strategies one can take to help speed up this process. |

Notice how in both of our explanations we took the source’s information and then added to the information to direct it for our specific purpose. In the case of the bullying citation, we then propose that businesses should either adopt workplace bullying guidelines or face legal intervention. In the case of the “aha!” example, we turn the quotation into a section on helping people find their thesis or topic. In both cases, we were able to use the information to further our speech.

Using Sources Ethically

The last section of this chapter is about using sources in an ethical manner. Whether you are using primary or secondary research, there are five basic ethical issues you need to consider.

Avoid Plagiarism

First, and foremost, if the idea isn’t yours, you need to cite where the information came from during your speech. Having the citation listed on a bibliography or reference page is only half of the correct citation. You must provide correct citations for all your sources within the speech as well. In a very helpful book called Avoiding Plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work , Menager-Beeley and Paulos provide a list of twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009):

- Do your own work, and use your own words. One of the goals of a public speaking class is to develop skills that you’ll use in the world outside academia. When you are in the workplace and the “real world,” you’ll be expected to think for yourself, so you might as well start learning this skill now.

- Allow yourself enough time to research the assignment. One of the most commonly cited excuses students give for plagiarism is that they didn’t have enough time to do the research. In this chapter, we’ve stressed the necessity of giving yourself plenty of time. The more complete your research strategy is from the very beginning, the more successful your research endeavors will be in the long run. Remember, not having adequate time to prepare is no excuse for plagiarism.

- Keep careful track of your sources. A common mistake that people can make is that they forget where information came from when they start creating the speech itself. Chances are you’re going to look at dozens of sources when preparing your speech, and it is very easy to suddenly find yourself believing that a piece of information is “common knowledge” and not citing that information within a speech. When you keep track of your sources, you’re less likely to inadvertently lose sources and not cite them correctly.

- Take careful notes. However you decide to keep track of the information you collect (old-fashioned pen and notebook or a computer software program), the more careful your note-taking is, the less likely you’ll find yourself inadvertently not citing information or citing the information incorrectly. It doesn’t matter what method you choose for taking research notes, but whatever you do, you need to be systematic to avoid plagiarizing.

- Assemble your thoughts, and make it clear who is speaking. When creating your speech, you need to make sure that you clearly differentiate your voice in the speech from the voice of specific authors of the sources you quote. The easiest way to do this is to set up a direct quotation or a paraphrase, as we’ve described in the preceding sections. Remember, audience members cannot see where the quotation marks are located within your speech text, so you need to clearly articulate with words and vocal tone when you are using someone else’s ideas within your speech.

- If you use an idea, a quotation, paraphrase, or summary, then credit the source. We can’t reiterate it enough: if it is not your idea, you need to tell your audience where the information came from. Giving credit is especially important when your speech includes a statistic, an original theory, or a fact that is not common knowledge.

- Learn how to cite sources correctly both in the body of your paper and in your List of Works Cited ( Reference Page ) . Most public speaking teachers will require that you turn in either a bibliography or reference page on the day you deliver a speech. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the bibliography or reference page is all they need to cite information, and then they don’t cite any of the material within the speech itself. A bibliography or reference page enables a reader or listener to find those sources after the fact, but you must also correctly cite those sources within the speech itself; otherwise, you are plagiarizing.

- Quote accurately and sparingly. A public speech should be based on factual information and references, but it shouldn’t be a string of direct quotations strung together. Experts recommend that no more than 10 percent of a paper or speech be direct quotations (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009). When selecting direct quotations, always ask yourself if the material could be paraphrased in a manner that would make it clearer for your audience. If the author wrote a sentence in a way that is just perfect, and you don’t want to tamper with it, then by all means directly quote the sentence. But if you’re just quoting because it’s easier than putting the ideas into your own words, this is not a legitimate reason for including direct quotations.

- Paraphrase carefully. Modifying an author’s words in this way is not simply a matter of replacing some of the words with synonyms. Instead, as Howard and Taggart explain in Research Matters , “paraphrasing force[s] you to understand your sources and to capture their meaning accurately in original words and sentences” (Howard & Taggart, 2010). Incorrect paraphrasing is one of the most common forms of inadvertent plagiarism by students. First and foremost, paraphrasing is putting the author’s argument, intent, or ideas into your own words.

- Do not patchwrite ( patchspeak ) . Menager-Beeley and Paulos define patchwriting as consisting “of mixing several references together and arranging paraphrases and quotations to constitute much of the paper. In essence, the student has assembled others’ work with a bit of embroidery here and there but with little original thinking or expression” (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009). Just as students can patchwrite, they can also engage in patchspeaking. In patchspeaking, students rely completely on taking quotations and paraphrases and weaving them together in a manner that is devoid of the student’s original thinking.

- Summarize, don’t auto-summarize. Some students have learned that most word processing features have an auto-summary function. The auto-summary function will take a ten-page document and summarize the information into a short paragraph. When someone uses the auto-summary function, the words that remain in the summary are still those of the original author, so this is not an ethical form of paraphrasing.

- Do not rework another student’s paper ( speech ) or buy paper mill papers ( speech mill speeches ) . In today’s Internet environment, there are a number of storehouses of student speeches on the Internet. Some of these speeches are freely available, while other websites charge money for getting access to one of their canned speeches. Whether you use a speech that is freely available or pay money for a speech, you are engaging in plagiarism. This is also true if the main substance of your speech was copied from a web page. Any time you try to present someone else’s ideas as your own during a speech, you are plagiarizing.

Avoid Academic Fraud

While there are numerous websites where you can download free speeches for your class, this is tantamount to fraud. If you didn’t do the research and write your own speech, then you are fraudulently trying to pass off someone else’s work as your own. In addition to being unethical, many institutions have student codes that forbid such activity. Penalties for academic fraud can be as severe as suspension or expulsion from your institution.

Don’t Mislead Your Audience

If you know a source is clearly biased, and you don’t spell this out for your audience, then you are purposefully trying to mislead or manipulate your audience. Instead, if the information may be biased, tell your audience that the information may be biased and allow your audience to decide whether to accept or disregard the information.

Give Author Credentials

You should always provide the author’s credentials. In a world where anyone can say anything and have it published on the Internet or even publish it in a book, we have to be skeptical of the information we see and hear. For this reason, it’s very important to provide your audience with background about the credentials of the authors you cite.

Use Primary Research Ethically

Lastly, if you are using primary research within your speech, you need to use it ethically as well. For example, if you tell your survey participants that the research is anonymous or confidential, then you need to make sure that you maintain their anonymity or confidentiality when you present those results. Furthermore, you also need to be respectful if someone says something is “off the record” during an interview. We must always maintain the privacy and confidentiality of participants during primary research, unless we have their express permission to reveal their names or other identifying information.

Key Takeaways

- Style focuses on the components of your speech that make up the form of your expression rather than your content.

- Social science disciplines, such as psychology, human communication, and business, typically use APA style, while humanities disciplines, such as English, philosophy, and rhetoric, typically use MLA style.

- The APA sixth edition and the MLA seventh edition are the most current style guides and the tables presented in this chapter provide specific examples of common citations for each of these styles.

- Citing sources within your speech is a three-step process: set up the citation, provide the cited information, and interpret the information within the context of your speech.

- A direct quotation is any time you utilize another individual’s words in a format that resembles the way they were originally said or written. On the other hand, a paraphrase is when you take someone’s ideas and restate them using your own words to convey the intended meaning.

- Ethically using sources means avoiding plagiarism, not engaging in academic fraud, making sure not to mislead your audience, providing credentials for your sources so the audience can make judgments about the material, and using primary research in ways that protect the identity of participants.

- Plagiarism is a huge problem and creeps its way into student writing and oral presentations. As ethical communicators, we must always give credit for the information we convey in our writing and our speeches.

- List what you think are the benefits of APA style and the benefits of MLA style. Why do you think some people prefer APA style over MLA style or vice versa?

- Find a direct quotation within a magazine article. Paraphrase that direct quotation. Then attempt to paraphrase the entire article as well. How would you cite each of these orally within the body of your speech?

- Which of Menager-Beeley and Paulos (2009) twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism do you think you need the most help with right now? Why? What can you do to overcome and avoid that pitfall?

American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. See also American Psychological Association. (2010). Concise rules of APA Style: The official pocket style guide from the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Howard, R. M., & Taggart, A. R. (2010). Research matters . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, p. 131.

Menager-Beeley, R., & Paulos, L. (2009). Understanding plagiarism: A student guide to writing your own work . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 5–8.

Modern Language Association. (2009). MLA handbook for writers of research papers (7th ed.). New York, NY: Modern Language Association.

Workplace Bullying Institute. (2009). Bullying: Getting away with it WBI Labor Day Study—September, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2011, from http://www.workplacebullying.org/res/WBI2009-B-Survey.html

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Speech: Citing Sources in APA

- Two Sides of an Issue Informative Speech

- Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Persuasive Speech

- Citing Sources in APA

- Evaluating Information

- Public Speaking Tips

How to Cite in Your Speech

- Oral Citations

To orally cite something, you will need to give sufficient information about the source. Typically, this is the author, title, and date of a source. By including this information, you allow your listeners to find your original sources, as well as allow them to hear that your sources are recent and are credible.

Source: Santa Fe College Library. (2023). Reading Scholarly Papers . https://sfcollege.libguides.com/speech/oral-citations

| Colonel Charles Hoge in his 2010 book coins the term 'rageaholism,' which refers to "persistent rage and hostility." |

|

|

|

|

How to Cite in Your Outline

- More APA Help

The first thing you want to figure out when you are creating a reference is what type of material you are referencing. Depending on what your item is, the reference will look slightly different. Check out the tabs for examples of how to cite.

Your Reference page should include the following:

- At the top, it should have the word References centered and in bold.

- References will be in alphabetical order by the first author's last name.

- The references will be double spaced and have hanging indentation . Hanging indentation means that the first line of the reference is all the way to the left, and the rest of the lines of the reference are indented.

|

Authorlastname, A. A. (Date of publication). . Publishing Company. |

| (Issue), page numbers. DOI (if available) Hang, W., & Banks, T. (2019). Machine learning applied to pack classification. (6), 601-620. Hickox, S. (2017). It’s time to rein in employer drug testing. (2), 419-462. |

| . Name of Site. URL Martin Lillie, C. M. (2016, December 30). . Mayo Clinic. If the site has an , leave off the name of the website. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, January 23). . If the site has , put the title of the webpage where the author would normally go. Birds: Living dinosaurs. (n.d.). American Museum of Natural History. |

Check out our APA Help Page for more in-depth information on citing in APA format.

- << Previous: Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Persuasive Speech

- Next: Evaluating Information >>

- Last Updated: Nov 2, 2023 10:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wctc.edu/speech

Citations & Avoiding Plagiarism

- Introduction to Citations

- 5 Steps to Create a Citation

- Citation Generators: How to Use & Doublecheck Them

- IEEE This link opens in a new window

- AI/ChatGPT and Citations

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- In-Text Citations

- Verbal Citations in Speeches

- Citation Help Playlist (YouTube) This link opens in a new window

- Links for Citation Generators Workshop

Why use Verbal Citations?

- Adds credibility.

- Shows your work.

- Avoids plagiarism by giving credit to others for their work/ideas.

- Shows timeliness of research and resources.

Creating an Verbal Citation

General guidelines.

Be brief, but p rovide enough information that your audience can track down the source.

Highlight what is most important criteria for that source.

Include who/what and when.

- Author

- Author's credentials

- Title of Work

- Title of Publication

- Date of work/publication/study

Use an introductory phrase for your verbal citation.

According to Professor Jane Smith at Stanford University.... (abbreviated verbal citation)

When I interviewed college instructor John Doe and observed his English 101 class...

Jason Hammersmith, a journalist with the Dallas Times, describes in his February 13, 2016 article.... (Full verbal citation)

Full vs. abbreviated verbal citations

Full verbal citations include all the information about the source thereby allowing the source to be easily found. ex. According to Harvard University professors, Dr. Smith and Dr. Jones research on this topic published in the Summer 2015 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine....

Abbreviated verbal citations include less information about the source, but still includes the most important aspects of that specific source. ex. A 2015 study in the New England Journal of Medicine reports that Harvard University professors....

- FILE: Guide to Oral Footnoting (a/k/a verbal citations) This document from Matt McGarrity, a University of Washington communication instructor, provides examples and tips on how to verbally cite information in a speech.

Speaking a Verbal Citation

Verbal citations should come at the beginning of the cited idea or quotation..

It is a easier for a listening audience to understand that what they hear next is coming from that source.

Introduce the quote (ex "And I quote" or "As Dr. Smith stated"...) PAUSE. Start quotation. PAUSE at the end of the quotation.

Introduce the quote. Say QUOTE. Start quotation. Say END QUOTE.

Example 1 : Listen to the first few minutes of this video to hear how the speaker incorporates a verbal citation.

2018 NSDA Informative Speech Champion Lily Indie's "Nobody puts Baby in a closet" has examples of verbal citations. Listen to two verbal citations starting at the 5:30 mark and running until 6:50 mark in this YouTube video.

- << Previous: In-Text Citations

- Next: Citation Help Playlist (YouTube) >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 10:26 AM

- URL: https://libguides.spokanefalls.edu/cite

- Lawrence W. Tyree Library

- Subject Guides

- Organizing & Citing Sources

- Developing a Topic

- How to Search

- Suggested Websites

Reading Scholarly Papers

Organizing Sources

All direct quotes, paraphrasing, summarizing, statistics, and outside opinions count as outside information, and must be cited. If you have never developed a system for keeping track of your citations, the following video provides an easy to use but effective system.

View Transcript

Hi, everyone! This is Lara Hammock from the Marble Jar channel and in today's video, I'll tell you how I use Google Sheets to organize my citations and sources for papers and research projects.

I'm in my first year of graduate school and we do a lot of writing. References and citations are very important, as they are for any discipline. I supposed if I was writing a dissertation with a hundred citations, I would feel the need to pay for and learn a whole complicated citation software, but since I'm not, I prefer to use tools that I already use and know well. AND despite the fact I'm not writing a dissertation, I have written some papers that have had over 25 sources, so I do need SOME kind of system to organize and manage my citations.

I started out, as most people do, with kind of a hodge-podge system of just cutting and pasting URLs from the Internet and sticking them at the bottom of the Word document of the paper. Or, if I'm doing research, I'd just copy and paste URLs with maybe some quotes from the study or article. The problem was, if I had multiple quotes, I couldn't organize them by topic for fear of losing the reference link, or I'd have to duplicate the URL multiple times. Plus, scrolling down to check these references was annoying. I needed a better, less messy system.

Here's what I do now. For each research project or paper, I create a new Google Sheets spreadsheet for references. You could easily do this in any spreadsheet program. I name it something like Class name - Project name - Citations and Quotes. Let's use a research project that I just did for my Policy class as an example. My spreadsheet name is "Policy - Ex-Felon Voting Rights Citations and Quotes." Then -- I make 2 tabs. The first tab is called Quotes, the second is Sources. I'm going to put a sample of this Citation Spreadsheet up on my Google Drive to share with you. To use it, just follow the link that I will provide in the notes section, make a copy into your own Drive, and then use it or modify it as you see fit.

Sample Google Spreadsheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1PaQbDLrTFptlZAlarTkdj_syYBxs1zUaqqXulF1e11A/edit?usp=sharing

Back to the spreadsheet -- so, now as I'm doing my research and reading a bunch of different articles -- in this case, mostly news articles and opinion pieces -- I starting finding quotes or statistics that help me to understand the issue or that I might want to use in my paper. So, I copy the quote and paste it into this first column. Okay -- the second column is a reference number. I'm going to want to remember where I got this quote from -- so go to the article and copy the URL or website address. I note some basics about the source and what the article is about -- in this case it's an Editorial from The Washington Post Editorial Board. Now I go into the Sources tab paste the URL under website address, note some basics about the article -- more for my own recall ability than anything else, and I number it -- #1. Now, I'm going to have a bunch of other articles to put in here, so I might as well go ahead and fill in these numbers, 1 to 10. Okay, back to the Quotes tab, I'm going to indicate that this quote came from article #1. Now, I can paste several quotes from the same article, I just need to indicate where they came from. So, here is my completed spreadsheet for this research project. I have 13 sources and 38 quotes. I obviously did not use all of those in my paper, but they helped to shape my understanding of the topic and served as a repository for the quotes and statistics that I DID end up using.

Just a quick note -- because of the nature of this research project, most of my sources were articles about current events, but this system also works great for scholarly research since so much is accessible on the Internet these days through your academic institution's research portal. I also use this system to capture quotes from books. Check out my video on exporting quotes from Kindle books into a spreadsheet such as this.

There are two things that I find really helpful about this system:

1) Easy to categorize - Because each quote has its own line, you can tag each quote with a theme or category. For example, in this column, I'm going to put in the main reasoning that states use to disenfranchise ex-offenders. There are a handful: safety, punishment, violation of social contract, political ideology, race etc. Not every quote is going to get a tag, but I can tag all of the ones that apply and then I can sort by this column. That way, if this is how I've decided to structure my paper, in this case -- by state rationale, I have quotes that are all nicely grouped together and ready to use for each topic. The second thing, is that this system makes it

2) Easy to cite while drafting - So, I'm writing my paper and I want to use a good statistic. Here's one: "McAuliffe's order affected 200,000 people in a state where 3.9 million people voted in the 2012 presidential election." So, I go ahead and quote this in my paper. Now, I don't want to slow down my writing process do the whole citation now (for me, that is an entirely different thinking process), so when I'm drafting, I just put the reference number in parenthesis right behind the quote. Like this (4). Then, once I've drafted and edited the paper, I go back in looking for reference numbers and replace them with proper citations. This is easy to do since I have a nice centralized place where I've gathered all of the source website information.

This system has worked well for me. Let me know what you think! Comments are always appreciated and thanks for watching!

You may also choose to organize your notes on sources in a more topical manner. For instance, you may have main points as a heading and include bullet points of quotes, information, and statistics. Be sure to include your sources!

TWITTER IN SCHOLARLY COMMUNICATION

- First conceived by Andrea Kuszewski in 2011

- “Liu notes that the hashtag was originally intended for science journalists, who typically lack access to the online library resources available to researchers at large universities; however, her research has demonstrated that academics and students use #icanhazpdf services more frequently than those in communications fields” (p. 7)

- “Such requests are evidence of users choosing social media over the library as a means of obtaining scholarly materials” (p. 11)

- https://www.altmetric.com/blog/interactions-the-numbers-behind-icanhazpdf

- “Specific tools, such as Twitter, have proved popular for frequent use by scholars to communicate with their counterparts and promote each other’s work” (Al-Aufi & Fulton, 2015, p. 228)

Now, how do you incorporate those sources into your writing? This wonderful video from ASU and Crash Course covers how you can use paraphrasing, quotations, and explanations without plagiarism.

Citing Your Sources

Ask your professor which style you should use for your class. APA, MLA, and Chicago are the three mostly commonly used citation styles at Santa Fe College, with APA being the most common citation style for speech classes.

- APA Citation Guide [Tyree Library] Guide created by the Tyree Library with information on formatting, example citations, and tutorials.

- APA Style Blog The official blog, answering and clarifying questions about APA.

- The Basics of APA Style Official tutorial on APA.

- Chicago-Style Citation Quick Guide Quick examples from the official style guide.

- Chicago Citation Guide [Tyree Library] Guide created by the Tyree Library with information on formatting, example citations, and tutorials.

- MLA Citation Guide [Tyree Library] Guide created by the Tyree Library with information on formatting, example citations, and tutorials.

- The MLA Style Center The official website for MLA style, with more examples, guidelines, and a place to ask questions.

Oral Citations

- Oral Citation Basics

To orally cite something, you will need to give sufficient information about the source to your audience. Typically, this is the author, title, and date of a source. By including this information, you allow your listeners to find your original sources, as well as allow them to hear that your sources are recent and are credible.

Orally Citing Information in Your Speech from Andrew Ishak on Vimeo .

Provide the author, title, and date of the book.

Colonel Charles Hoge in his 2010 book Once a Warrior, Always a Warrior coins the term 'rageaholism,' which refers to "persistent rage and hostility."

Provide the author, publication name, and date.

The recent 2013 Law & Human Behavior article by Kahn, Byrd, and Pardini, shows that young men who have high callous-unemotional traits, such as a lack of empathy, are more likely to be arrested for serious crimes.

Provide the website title and date.

In a March 2014 piece on the Blue Review website, anthropologist John Ziker found that college professors spend 17% of their day in meetings.

Provide the name of the interviewer (if not you), the name and credentials of the interviewee, and the date.

In an February 25 interview with Jon Stewart on The Daily Show , Michio Kaku notes that memories can currently be uploaded into mice, and eventually this could be used to help sufferers of Alzheimer's disease.

- << Previous: Suggested Websites

- Next: Get Help >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 3:48 PM

- URL: https://sfcollege.libguides.com/speech

Commitment to Equal Access and Equal Opportunity

Santa Fe College is committed to an environment that embraces diversity, respects the rights of all individuals, is open and accessible, and is free of harassment and discrimination. For more information, visit sfcollege.edu/eaeo or contact [email protected] .

SACSCOC Accreditation Statement

Santa Fe College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). For more information, visit sfcollege.edu/sacscoc .

PRDV008: Preparing and Delivering Presentations (2020.A.01)

How to cite your sources.

Read this article, which offers more specifics on giving citations during your presentation.

Citing Sources in a Speech

Once you have decided what sources best help you explain important terms and ideas in your speech or help you build your arguments, it is time to place them into your speech. In this section, we are going to quickly talk about using your research effectively in your speeches. Citing sources within a speech is a three-step process: set up the citation, give the citation, and explain the citation.

First, you want to set up your audience for the citation. The setup is one or two sentences that are general statements that lead to the specific information you are going to discuss from your source.

Here is an example: "Workplace bullying is becoming an increasing problem for U.S. organizations". Notice that this statement does not provide a specific citation yet, but the statement introduces the basic topic.

Second, you want to deliver the source; whether it is a direct quotation or a paraphrase of information from a source does not matter at this point.

A direct quotation is when you cite the actual words from a source with no changes. To paraphrase is to take a source's basic idea and condense it using your own words.

Here is an example of both:

| Direct Quotation | In a 2009 report titled , the Workplace Bullying Institute wrote, "Doing nothing to the bully (ensuring impunity) was the most common employer tactic (54%)". |

| Paraphrase | According to a 2009 study by the Workplace Bullying Institute titled , when employees reported bullying, 54 percent of employers did nothing at all. |

You will notice that in both of these cases, we started by citing the author of the study – in this case, the Workplace Bullying Institute. We then provided the title of the study. You could also provide the name of the article, book, podcast, movie, or other sources. In the direct quotation example, we took information right from the report.

In the second example, we summarized the same information. Workplace Bullying Institute. (2009). Bullying: Getting Away with It WBI Labor Day Study – September 2009.

Let's look at another example of direct quotations and paraphrases, this time using a person, rather than an institution, as the author.

| Direct Quotation | In her book , Mary George, senior reference librarian at Princeton University's library, defines insight as something that "occurs at an unpredictable point in the research process and leads to the formulation of a thesis statement and argument. Also called an 'Aha' moment or focus". |

| Paraphrase | In her book , Mary George, senior reference librarian at Princeton University's library, tells us that insight is likely to come unexpectedly during the research process; it will be an "aha!" moment when we suddenly have a clear vision of the point we want to make. |

Notice that the same basic pattern for citing sources was followed in both cases.

The final step in correct source citation within a speech is the explanation. One of the biggest mistakes of novice public speakers (and research writers) is that they include a source citation and then do nothing with the citation at all. Instead, take the time to explain the quotation or paraphrase to put into the context of your speech.

Do not let your audience draw their own conclusions about the quotation or paraphrase. Instead, help them make the connections you want them to make. Here are two examples using the examples above:

| Bullying Example | Clearly, organizations need to be held accountable for investigating bullying allegations. If organizations will not voluntarily improve their handling of this problem, the legal system may be required to step in and enforce sanctions for bullying, much as it has done with sexual harassment. |

| Aha! Example | As many of us know, reaching that "aha!" moment does not always come quickly, but there are definitely some strategies one can take to help speed up this process. |

Notice how in both of our explanations we took the source's information and then added to the information to direct it for our specific purpose. In the case of the bullying citation, we then propose that businesses should either adopt workplace bullying guidelines or face legal intervention. In the case of the "aha!" example, we turn the quotation into a section on helping people find their thesis or topic. In both cases, we were able to use the information to further our speech.

Using Sources Ethically

The last section of this chapter is about using sources in an ethical manner. Whether you are using primary or secondary research, there are five basic ethical issues you need to consider.

Avoid Plagiarism

First, and foremost, if the idea is not yours, you need to cite where the information came from during your speech. Having the citation listed on a bibliography or reference page is only half of the correct citation. You must provide correct citations for all your sources within the speech as well.

In a very helpful book called Avoiding Plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work , Menager-Beeley and Paulos provide a list of twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism: Menager-Beeley, R., & Paulos, L. (2009). Understanding Plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 5–8.

- Do your own work, and use your own words. One of the goals of a public speaking class is to develop skills that you will use in the world outside academia. When you are in the workplace and the "real world", you will be expected to think for yourself, so you might as well start learning this skill now.

- Allow yourself enough time to research the assignment. One of the most commonly cited excuses students give for plagiarism is that they did not have enough time to do the research. In this chapter, we have stressed the necessity of giving yourself plenty of time. The more complete your research strategy is from the very beginning, the more successful your research endeavors will be in the long run. Remember, not having adequate time to prepare is no excuse for plagiarism.

- Keep careful track of your sources. A common mistake that people can make is that they forget where information came from when they start creating the speech itself. Chances are you are going to look at dozens of sources when preparing your speech, and it is very easy to suddenly find yourself believing that a piece of information is "common knowledge" and not citing that information within a speech. When you keep track of your sources, you are less likely to inadvertently lose sources and not cite them correctly.

- Take careful notes. However you decide to keep track of the information you collect (old-fashioned pen and notebook or a computer software program), the more careful your note-taking is, the less likely you will find yourself inadvertently not citing information or citing the information incorrectly. It does not matter what method you choose for taking research notes, but whatever you do, you need to be systematic to avoid plagiarizing.

- Assemble your thoughts, and make it clear who is speaking. When creating your speech, you need to make sure that you clearly differentiate your voice in the speech from the voice of specific authors of the sources you quote. The easiest way to do this is to set up a direct quotation or a paraphrase, as we have described in the preceding sections. Remember, audience members cannot see where the quotation marks are located within your speech text, so you need to clearly articulate with words and vocal tone when you are using someone else's ideas within your speech.

- If you use an idea, a quotation, paraphrase, or summary, then credit the source. We cannot reiterate it enough: if it is not your idea, you need to tell your audience where the information came from. Giving credit is especially important when your speech includes a statistic, an original theory, or a fact that is not common knowledge.

- Learn how to cite sources correctly both in the body of your paper and in your List of Works Cited ( Reference Page ). Most public speaking teachers will require that you turn in either a bibliography or reference page on the day you deliver a speech. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the bibliography or reference page is all they need to cite information, and then they do not cite any of the material within the speech itself. A bibliography or reference page enables a reader or listener to find those sources after the fact, but you must also correctly cite those sources within the speech itself; otherwise, you are plagiarizing.

- Quote accurately and sparingly. A public speech should be based on factual information and references, but it should not be a string of direct quotations strung together. Experts recommend that no more than 10 percent of a paper or speech be direct quotations. Menager-Beeley, R., & Paulos, L. (2009). Understanding Plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. When selecting direct quotations, always ask yourself if the material could be paraphrased in a manner that would make it clearer for your audience. If the author wrote a sentence in a way that is just perfect, and you do not want to tamper with it, then by all means directly quote the sentence. But if you are just quoting because it is easier than putting the ideas into your own words, this is not a legitimate reason for including direct quotations.

- Paraphrase carefully. Modifying an author's words in this way is not simply a matter of replacing some of the words with synonyms. Instead, as Howard and Taggart explain in Research Matters , "paraphrasing force[s] you to understand your sources and to capture their meaning accurately in original words and sentences". Howard, R. M., & Taggart, A. R. (2010). Research Matters . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, p. 131. Incorrect paraphrasing is one of the most common forms of inadvertent plagiarism by students. First and foremost, paraphrasing is putting the author's argument, intent, or ideas into your own words.

- Do not patchwrite ( patchspeak ). Menager-Beeley and Paulos define patchwriting as consisting "of mixing several references together and arranging paraphrases and quotations to constitute much of the paper. In essence, the student has assembled others' work with a bit of embroidery here and there but with little original thinking or expression". Menager-Beeley, R., & Paulos, L. (2009). Understanding plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 7–8. Just as students can patchwrite, they can also engage in patchspeaking. In patchspeaking, students rely completely on taking quotations and paraphrases and weaving them together in a manner that is devoid of the student's original thinking.

- Summarize, do not auto-summarize. Some students have learned that most word processing features have an auto-summary function. The auto-summary function will take a ten-page document and summarize the information into a short paragraph. When someone uses the auto-summary function, the words that remain in the summary are still those of the original author, so this is not an ethical form of paraphrasing.

- Do not rework another student's paper ( speech ) or buy paper mill papers ( speech mill speeches ). In today's Internet environment, there are a number of storehouses of student speeches on the Internet. Some of these speeches are freely available, while other websites charge money for getting access to one of their canned speeches. Whether you use a speech that is freely available or pay money for a speech, you are engaging in plagiarism. This is also true if the main substance of your speech was copied from a web page. Any time you try to present someone else's ideas as your own during a speech, you are plagiarizing.

Avoid Academic Fraud

While there are numerous websites where you can download free speeches for your class, this is tantamount to fraud. If you did not do the research and write your own speech, then you are fraudulently trying to pass off someone else's work as your own. In addition to being unethical, many institutions have student codes that forbid such activity. Penalties for academic fraud can be as severe as suspension or expulsion from your institution.

Do not Mislead Your Audience

If you know a source is clearly biased, and you do not spell this out for your audience, then you are purposefully trying to mislead or manipulate your audience. Instead, if the information may be biased, tell your audience that the information may be biased and allow your audience to decide whether to accept or disregard the information.

Give Author Credentials

You should always provide the author's credentials. In a world where anyone can say anything and have it published on the Internet or even publish it in a book, we have to be skeptical of the information we see and hear. For this reason, it is very important to provide your audience with background about the credentials of the authors you cite.

Use Primary Research Ethically