- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

The Legacy of Order 9066 and Japanese American Internment

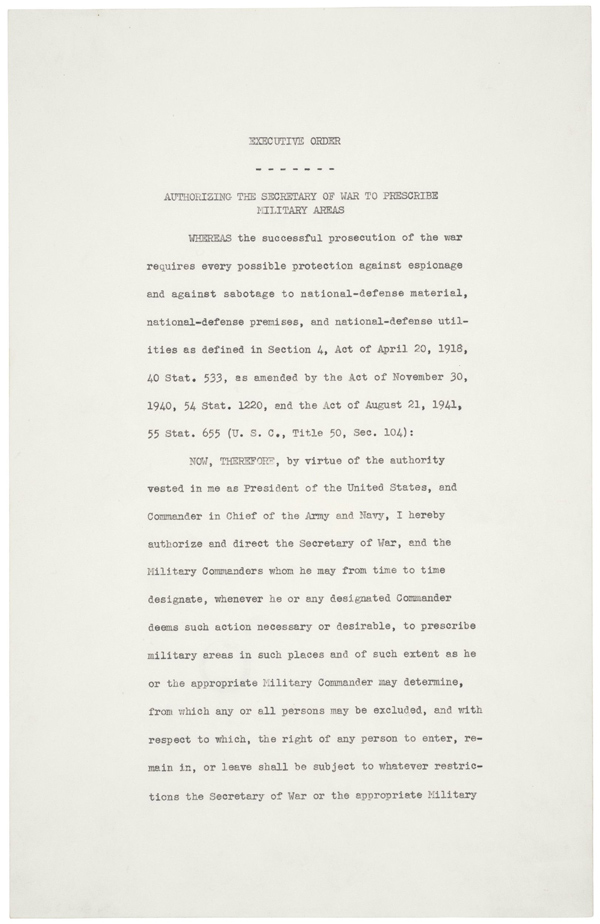

On Feb. 19, 1942, Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 , granting Secretary of War Henry Lewis Stimson and his commanders the power “to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded.” While the order named no specific group or location, nearly all Japanese American citizens on the West Coast were soon forced to uproot themselves and their families for relocation to internment camps. For three years, Japanese Americans were forced to live in sparse conditions, surrounded by barbed wire under a continuous cloud of suspicion and threat. Seventy-five years later, the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II has widely been denounced as racist and xenophobic and a period of national shame.

The order was issued two months after the Japanese military attack on Pearl Harbor , but its targeting of Japanese Americans and the resulting incarceration also had roots in a long history of racist and anti-Asian immigrant federal policies that stretched back to restrictive immigration policies of the late 1800s . Despite lack of any evidence supporting suspicions that Japanese Americans posed a significant threat as saboteurs and concerns about the infringement of civil liberties , political weight was thrown behind the idea of rounding up Japanese Americans on the West Coast and moving them to detention centers in the interior of the country in the name of national security ( John J. McCloy , assistant secretary of war, famously said that if the choice was between national security and civil liberties enshrined in the U.S. Constitution , the Constitution “was just a scrap of paper”).

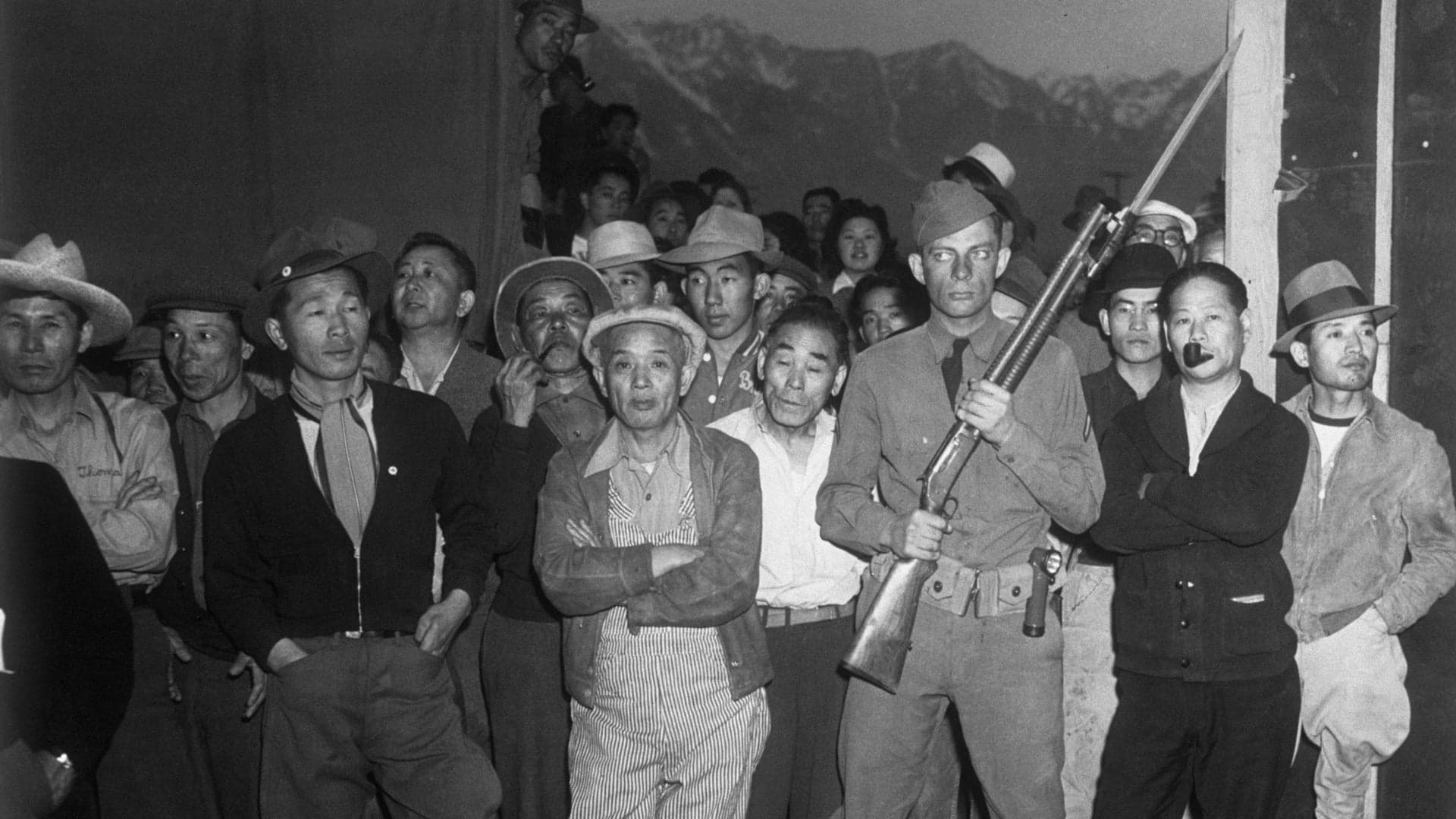

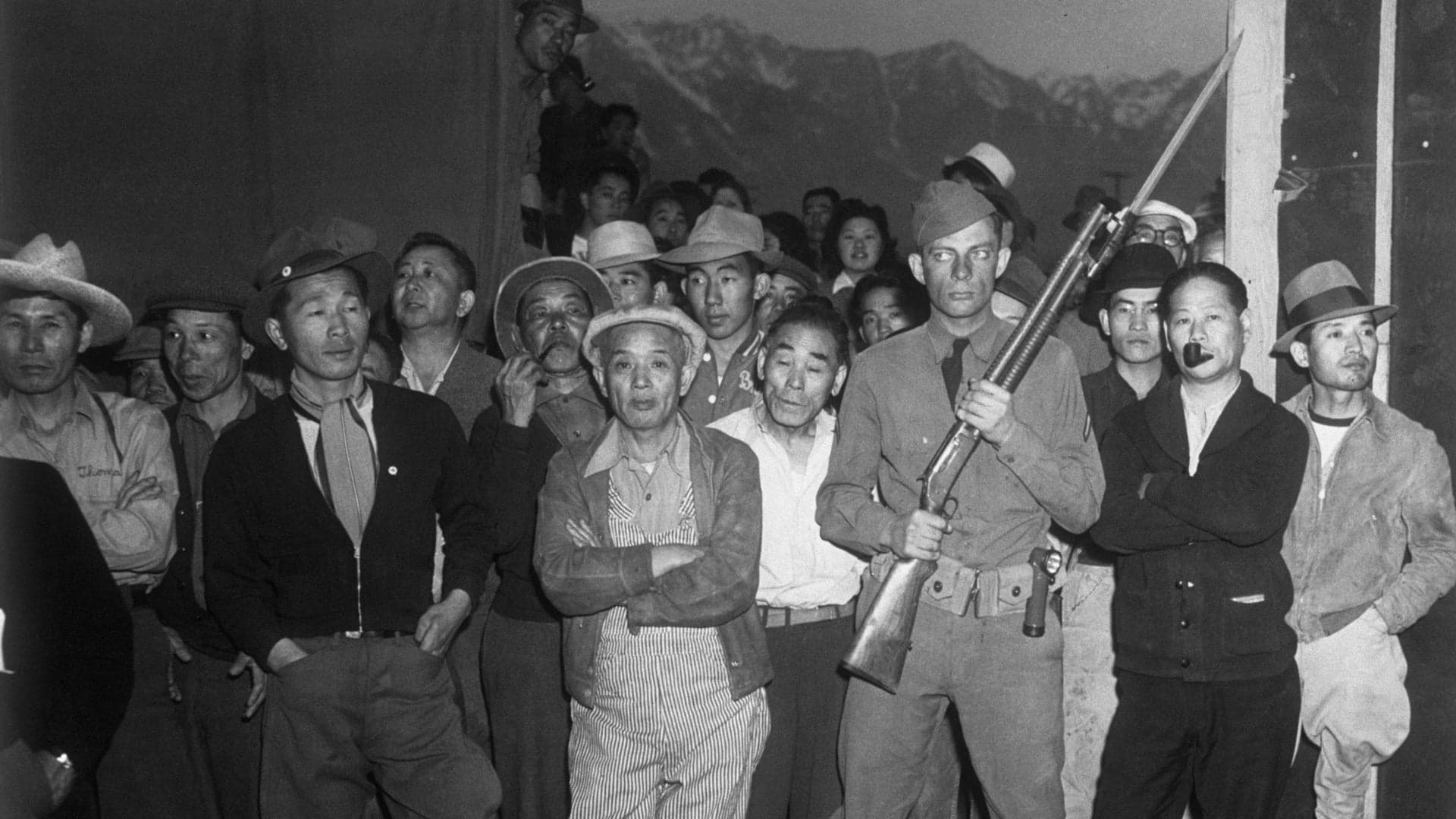

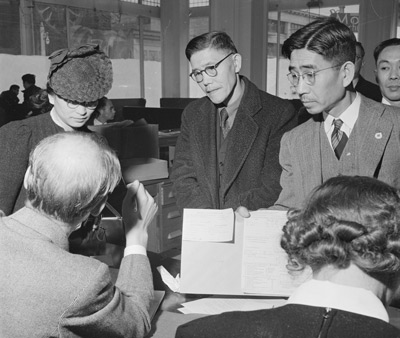

After a brief period of being subjected to nighttime curfews, on March 31, 1942, Japanese Americans who lived on the West Coast were ordered to register themselves and their family members and were forced to leave whatever they couldn’t carry behind; many had no choice but to sell their property and businesses for a fraction of their worth, often to their own neighbors and former friends. From 1942 to 1945, roughly 120,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese heritage were incarcerated at 1 of 10 camps located in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas. Living conditions were bare bones, with uninsulated barracks heated by coal-burning stoves, common latrines, little hot running water, and food being rationed. Although Japanese Americans attempted to create a semblance of community by setting up schools, sports, and other activities, they did so under the constant watch of armed guards with orders to shoot anyone who tried to leave.

The incarceration sparked various protests and legal fights, notably Korematsu v. United States , which ruled 6–3 to uphold the conviction of Fred Korematsu for refusing to submit to the order. However, in 2011, the U.S. solicitor general confirmed that the predecessor who had argued for the government in this case had lied to the court by withholding a U.S. Naval Intelligence report concluding that Japanese Americans didn’t pose a threat to the U.S. at the time. While the last camp was finally closed in 1946, it wasn’t until 1976 that Pres. Gerald Ford officially rescinded Executive Order 9066, stating: “We now know what we should have known then—not only was that evacuation wrong, but Japanese Americans were and are loyal Americans….I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise—that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.”

In 1988, Congress formally apologized to Japanese Americans, and the Civil Liberties Act awarded $20,000 each to some 80,000 surviving internees and their families. While presidential commissions have attributed the order to racial prejudice , war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership, even 75 years later the legacy of Executive Order 9066 still reverberates as some scholars and politicians continue to attempt justifying the incarceration of Japanese American citizens, using this shameful period of American history as a blueprint for further xenophobic policies targeting other immigrants and American citizens.

Learn More About This Topic

- Learn more about Executive Order 9066

- What is the term for second-generation U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants?

- Actor George Takei has spoken of his childhood spent at this internment camp

- Which U.S. department opposed moving innocent civilians to internment camps?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : February 19

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

FDR orders Japanese Americans into internment camps

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, initiating a controversial World War II policy with lasting consequences for Japanese Americans. The document ordered the forced removal of resident "enemy aliens" from parts of the West vaguely identified as military areas.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in 1941, Roosevelt came under increasing pressure by military and political advisors to address the nation’s fears of further Japanese attack or sabotage, particularly on the West Coast, where naval ports, commercial shipping and agriculture were most vulnerable. Included in the off-limits military areas referred to in the order were ill-defined areas around West Coast cities, ports and industrial and agricultural regions. While 9066 also affected Italian and German Americans, the largest numbers of detainees were by far Japanese Americans.

On the West Coast, long-standing racism against Japanese Americans, motivated in part by jealousy over their commercial success, erupted after Pearl Harbor into furious demands to remove them en masse to Relocation Centers for the duration of the war.

Japanese immigrants and their descendants, regardless of American citizenship status or length of residence, were systematically rounded up and placed in prison camps. Evacuees, as they were sometimes called, could take only as many possessions as they could carry and were forcibly placed in crude, cramped quarters. In the western states, camps on remote and barren sites such as Manzanar and Tule Lake housed thousands of families whose lives were interrupted and in some cases destroyed by Executive Order 9066. Many lost businesses, farms and loved ones as a result.

Roosevelt delegated enforcement of 9066 to the War Department, telling Secretary of War Henry Stimson to be as reasonable as possible in executing the order. Attorney General Francis Biddle recalled Roosevelt’s grim determination to do whatever he thought was necessary to win the war. Biddle observed that Roosevelt was not much concerned with the gravity or implications of issuing an order that essentially contradicted the Bill of Rights .

In her memoirs, Eleanor Roosevelt recalled being completely floored by her husband’s action. A fierce proponent of civil rights, Eleanor hoped to change Roosevelt’s mind, but when she brought the subject up with him, he interrupted her and told her never to mention it again.

During the war, the U.S. Supreme Court heard two cases challenging the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, upholding it both times. Finally, on February 19, 1976, decades after the war, Gerald Ford signed an order prohibiting the executive branch from re-instituting the notorious and tragic World War II order. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan issued a public apology on behalf of the government and authorized reparations for former Japanese American internees or their descendants.

Japanese Internment Camps

Executive Order 9066 On February 19, 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 with the stated intention of preventing espionage on American shores. Military zones were created in California, Washington and Oregon—states with a large population of Japanese Americans. Then Roosevelt’s executive order forcibly removed […]

U.S. Propaganda Film Shows ‘Normal’ Life in WWII Japanese Internment Camps

The U.S. government, for its part, tried to assure the rest of the country that its policy was justified, and that those Japanese Americans forced to live in the prison camps were happy.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s Work to Oppose Japanese Internment

The first lady did what she could to support Japanese Americans during WWII—without appearing to defy FDR's Executive Order 9066.

Also on This Day in History February | 19

John Singleton, 24, becomes first Black director nominated for an Oscar

"the feminine mystique" by betty friedan is published.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on February 19

Tiger woods apologizes for extramarital affairs, polish astronomer copernicus is born, aaron burr arrested for alleged treason.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

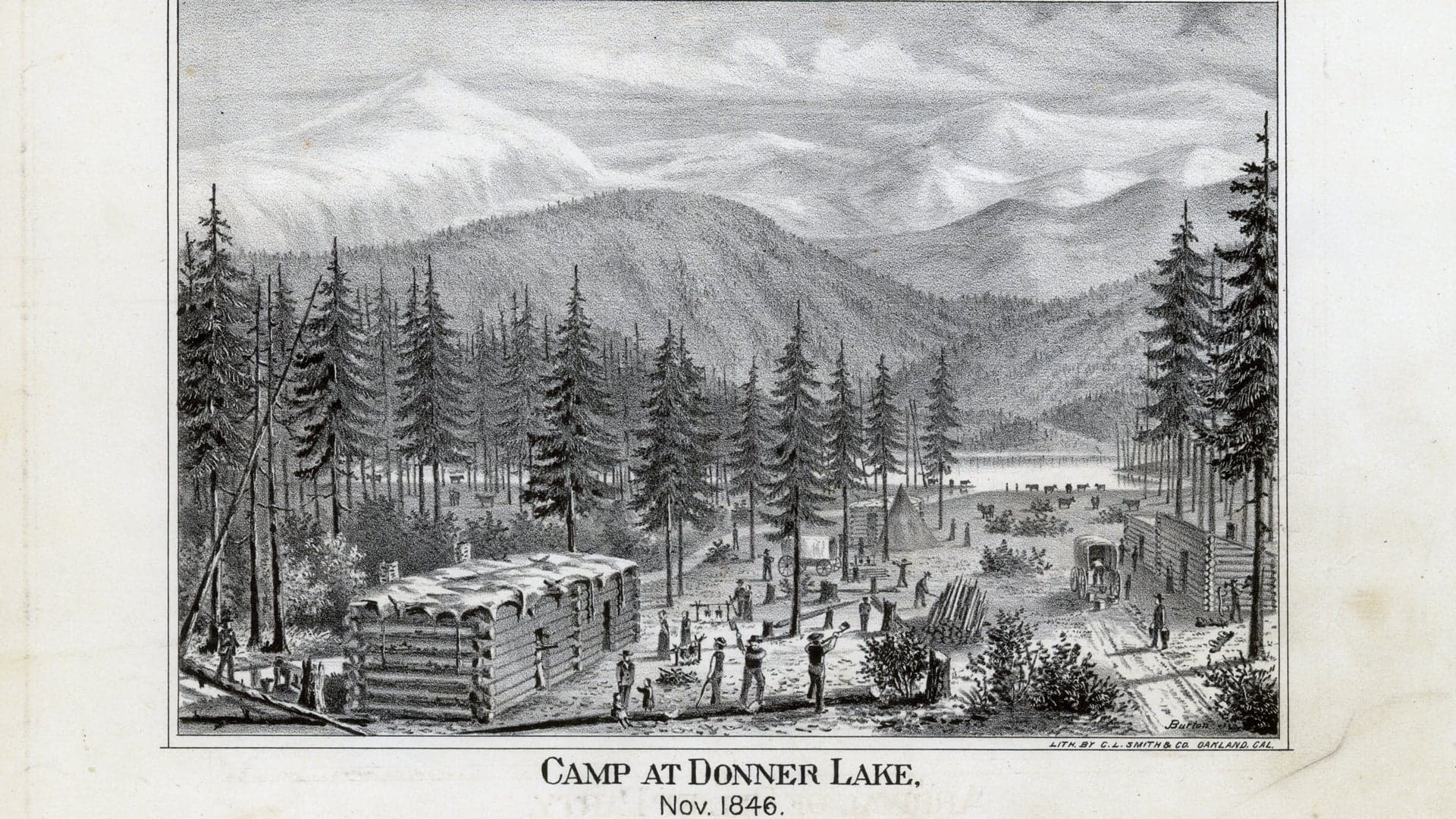

Donner Party rescued from the Sierra Nevada Mountains

U.s. marines invade iwo jima, chicago seven acquitted of conspiracy charges, thomas edison patents the phonograph, united states calls situation in el salvador "a communist plot", congress overlooks benedict arnold for promotion.

- Career Services

- USC Law Library

- About USC Gould

- Mission Statement

- Message from the Dean

- History of USC Gould

- Board of Councilors

- Jurist-in-Residence Program

- Social Media

- Consumer Information (ABA Required Disclosures)

- Contact USC Gould School of Law

- Academic Calendar

- LLM Programs

- Legal Master’s Programs

- Certificates

- Undergraduate Programs

- Bar Admissions

- Concentrations

- Corporate & Custom Education

- Course Descriptions

- Experiential Learning and Externships

- Progressive Degree Programs

Faculty & Research

- Faculty and Lecturer Directory

- Research and Scholarship

- Faculty in the News

- Distinctions and Awards

- Centers and Initiatives

- Workshops and Conferences

- Alumni Association

- Alumni Events

- USC Gould Alumni Class Notes

- USC Law Magazine

- Contact USC Gould Alumni Relations

- Student Life Office

- Student Life and Organizations

- Commencement

- Academic Services and Honors Programs

- Student Wellbeing

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging

- Law School Resources

- USC Resources

- Business Law & Economics

- Constitutional Law

- New Building Initiative

- Law Leadership Society

- How to Give to USC Gould

- Gift Planning

- BS Legal Studies

Explore by Interest

- Legal Master’s Programs

Quick Links

- Graduate & International Programs

- Giving to Gould

- How to Give

75 Years Later: The Impact of Executive Order 9066

Five USC Gould students reflect upon the time their families spent interned in camps during WWII

On Feb. 19, 1942 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed “Executive Order 9066,” which paved the way for the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese-Americans from the West Coast during World War II.

Families were forced to leave their homes and businesses and move inland to camps, sometimes thousands of miles from home. Many families were not allowed to return to their homes for years. The same Order led to one of the most infamous cases in the history of the United States Supreme Court, Korematsu v. United States , 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

| Cynthia Chiu '19's high school-age grandmother, photographed at the internment camp in Jerome, Arkansas |

| Mike Mikawa '17 and his grandparents |

| Tule Lake Segregation Center Prison, photo by Mike Mikawa '17 |

| Camp Jerome, 1944, as depicted in Cynthia Chiu's grandmother's yearbook |

| Mike Mikawa '17 visiting Poston site. |

| Cynthia Chiu's grandfather, who was sent to Italy with the 442nd Regiment. |

| A photo from Mike Mikawa's 2008 visit to the Manzanar Memorial. |

Explore Related

- Immigration Law

Related Stories

The Power of Social Activism

Lights, cameras, legal matters.

USC Gould School of Law 699 Exposition Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90089-0071 213-740-7331

USC Gould School of Law

699 Exposition Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90089-0071

- Academic Programs

- Acceptances

- Articles and Book Chapters

- Awards and Honors

- Book Chapters

- Book Reviews

- Business Law and Economics

- Center for Dispute Resolution

- Center for Law and Philosophy

- Center for Law and Social Science

- Center for Law History and Culture

- Center for Transnational Law and Business

- Centers and Institutes

- Continuing Legal Education

- Contribution to Amicus Briefs

- Contributions to Books

- Criminal Justice

- Degree Programs

- Dispute Resolution

- Election Law

- Experiential Learning

- Externships

- Graduate & International Programs

- Hidden Articles

- Housing Law and Policy Clinic

- Immigration Clinic

- Initiative and Referendum Institute

- Institute for Corporate Counsel

- Institute on Entertainment Law and Business

- Intellectual Property and Technology Law Clinic

- Intellectual Property Institute

- International Human Rights Clinic

- International Law

- Jurist in Residence

- Legal History

- Legal Theory and Jurisprudence

- LLM On Campus

- Media Advisories

- Media, Entertainment and Technology Law

- Mediation Clinic

- MSL On Campus

- Other Publications

- Other Works

- Planned Giving

- Post-Conviction Justice Project

- Practitioner Guides

- Presentations / Lectures / Workshops

- Public Interest Law

- Publications

- Publications and Shorter Works

- Publications in Books

- Publications in Law Reviews

- Publications in Peer-reviewed Journals

- Real Estate Law and Business Forum

- Redefined Blog

- Research & Scholarship

- Saks Institute for Mental Health Law, Policy, and Ethics

- Scholarly Publications

- Short Pieces

- Small Business Clinic

- Tax Institute

- Trust and Estate Conference

- Uncategorized

- Undergraduate Law

- Working Papers

- Works in Progress

Copyright © 2024 USC Gould. All Rights Reserved.

- For the Media

- Make a Gift

- Emergency Information

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Non-Discrimination

- Digital Accessibility

- Contact Webmaster

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

Executive Order 9066

10 pages • 20 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Order Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “order 9066”.

Executive Order 9066 was a piece of legislation issued by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II on February 19, 1942. The order granted the secretary of war and his commanders the power to declare particular sections of the country as military areas and to force the removal of people deemed to be “enemy aliens” from such areas. The document had particularly serious consequences for Japanese Americans, about 122,000 of whom were forcibly removed from their homes on the West Coast of the US and evacuated to internment camps for the remainder of the war. German and Italian Americans were similarly impacted, though to a much lesser degree.

Order 9066 is highly controversial as an instance in which the US government targeted ethnic or racial groups and denied them their civil liberties in the interest of national security. President Roosevelt issued the order in the wake of pressure from lobbyists on the West Coast of the US and in the face of objections of some members of Congress. Although several Japanese Americans challenged the order in court cases—including Korematsu v. United States —the Supreme Court upheld its legality; in Ex parte Mitsuye Endo , however, the Court placed limitations on the military’s ability to detain citizens for extended periods and paved the way for the dissolution of the internment camps.

Starting with that court decision, and even more so in the years and decades after the war, the tide turned against Order 9066, and Japanese Americans sought and received reparations for the government’s actions. In June 1946, President Harry Truman ordered the liquidation of the War Relocation Authority and allowed the internees to return home (“ Japanese-American Internment .” Harry S. Truman Library Museum ). Thirty years later, in 1976, President Gerald Ford formally prohibited the government from ever reinstituting Order 9066, and in 1988 President Ronald Reagan issued an apology and partial monetary restitution to the former internees and their heirs.

Content Warning : Some of the source material referred to in this guide uses outdated, offensive terms for Japanese people, which is replicated in this guide only in direct quotes of the source material.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt situates Executive Order 9066 in continuity with a line of legislation dealing with national defense and protecting the US from espionage and sabotage going back to the end of World War I.

Invoking his authority as president of the United States and commander in chief of the Army and Navy, Roosevelt authorizes the secretary of war and the commanders of the military under him to designate as “military areas” such places as they determine and to exclude “any or all persons” from said areas. At the same time, Roosevelt authorizes the secretary of war to provide transportation, food, shelter, and other necessary accommodations to persons so excluded. The designation of military areas shall supersede previous legislation on “prohibited and restricted areas” made in the immediate aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, as well as the present authority of the attorney general.

Roosevelt gives the military permission to use federal troops or agencies to enforce the order in individual “military areas.” He also authorizes the agencies of the federal government to assist the military in carrying out the order, including by providing medical aid, food, transportation, etc.

Finally, Roosevelt stresses that this order does not modify or limit the powers granted to the FBI, the attorney general, and the Department of Justice by previous legislation on securing national defense and prosecuting sabotage; the exception is when those laws are “superseded” by the designation of military areas under the present order.

Related Titles

By Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Four Freedoms Speech

Featured Collections

Books on U.S. History

View Collection

Politics & Government

School Book List Titles

World War II

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Franklin D. Roosevelt — A Research on the Executive Order 9066 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Demonstration of the Abuse of Power by the President

A Research on The Executive Order 9066 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and The Demonstration of The Abuse of Power by The President

- Categories: Franklin D. Roosevelt

About this sample

Words: 1055 |

Published: Oct 31, 2018

Words: 1055 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

In-Class Essay: Executive Order 9066

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 784 words

1 pages / 497 words

2 pages / 1137 words

4 pages / 1731 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Franklin D. Roosevelt

Roosevelt's Letter to His Son, also known as Theodore Roosevelt's "The Strenuous Life" letter, is a remarkable piece of writing that provides valuable insight into Roosevelt's beliefs and attitudes towards life. In this letter, [...]

The 32nd President of the United States and serving the longest in American history, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) has been called a great leader, humanitarian, skilled politician, and self-confident. The American people were [...]

The unemployment rate rose sharply during the Great Depression and reached its peak at the moment Franklin D. Roosevelt took office. As New Deal programs were enacted, the unemployment rate gradually lowered. ( Bureau of Labor [...]

The Great Depression really affected how things were going in America. Franklin D. Roosevelt was the president who had to address this issue. It was something that the president was optimistic on, stating that he “Promised a new [...]

In 1939 the Presidential Library system began thanks to President Franklin D. Roosevelt after he donated all of his presidential papers to the Federal Government to keep. President Roosevelt also donated part of his Hyde Park [...]

Are the United States of America officially getting on the back of the tiger? In JFK’s inaugural speech found in Norton Reader, he famously said, “those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside” [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Educator Resources

Japanese-American Incarceration During World War II

In his speech to Congress, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was "a date which will live in infamy." The attack launched the United States fully into the two theaters of World War II – Europe and the Pacific. Prior to Pearl Harbor, the United States had been involved in a non-combat role, through the Lend-Lease Program that supplied England, China, Russia, and other anti-fascist countries of Europe with munitions.

The attack on Pearl Harbor also launched a rash of fear about national security, especially on the West Coast. In February 1942, just two months later, President Roosevelt, as commander-in-chief, issued Executive Order 9066 that resulted in the internment of Japanese Americans. The order authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to evacuate all persons deemed a threat from the West Coast to internment camps, that the government called "relocation centers," further inland. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

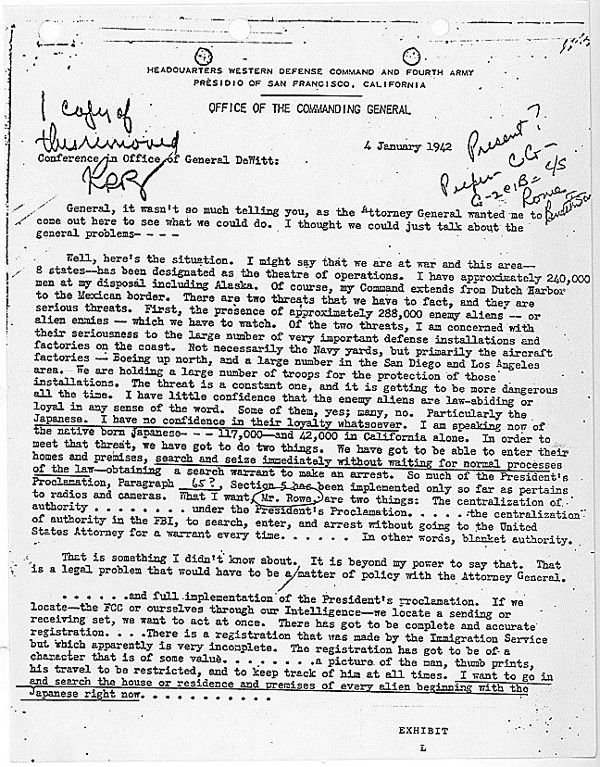

Meeting Between Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt and Representatives of the Department of Justice and the Army at the Office of Commanding General, Headquarters, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, in San Francisco, 1/4/1942

Executive Order 9066 Issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 2/19/1942

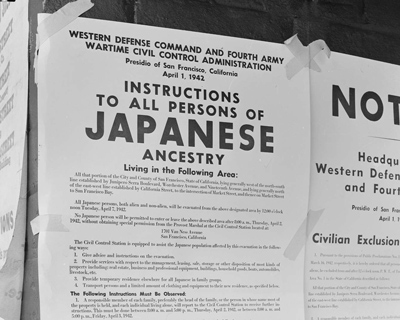

Posting of Exclusion Order in San Francisco, Directing Removal of Persons of Japanese Ancestry from the First Section in San Francisco to be Affected by the Evacuation, 4/11/1942

Thank You Note at the Iseri Drugstore in "Little Tokyo" in Los Angeles, California, 4/11/1942

Merchandise Sale in San Francisco, California, Where Customers Buy Goods Prior to Evacuation and Internment, 4/4/1942

Children Pledge Allegiance to the Flag in San Francisco, California, at Raphael Weill Public School, 4/20/1942

The Shibuya Family at Their Home in Mountain View, California, Before Being Sent to Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming Days Later, 4/18/1942

Ranch Superintendent Henry Futamachi (Left) Discusses Agriculture with Ranch Owner John MacKinley Before Evacuation and Internment, 4/10/1942

Dave Tatsuno Reading to His Son and Packing His Possessions Prior to Evacuation and Internment, 4/13/1942

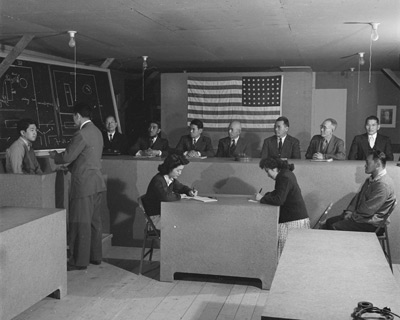

Residents of Japanese Ancestry File Forms in San Francisco, Two Days Before Evacuation and Internment, 4/4/1942

Residents of Japanese Ancestry, With Baggage Stacked, Waiting for a Bus to be Evacuated at the Wartime Civil Control Administration in San Francisco, 4/6/1942

Japanese Family Heads and Persons Living Alone Line up for "Processing" in Response to Civilian Exclusion Order Number 20, 4/25/1942

Baggage Being Sorted and Trucked to Owners in Their Barracks at the Minidoka Internment Camp in Eden, Idaho, 8/17/1942

Registering and Assigning Barracks to the Newly Arrived at Minidoka Internment Camp in Eden, Idaho, 8/17/1942

The Hirano Family Posing with a Photograph of a United States Serviceman at the Colorado River Internment Camp in Poston, Arizona

High School Campus at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming — Classes are Held in Tarpaper-covered, Barrack-style Buildings, 6/1943

The Poster Crew at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, Making Fire and Safety Posters, Announcements for Public Gatherings and Dances, and General Instructions, 9/14/1942

Court Session at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, Presiding Over Infractions of Camp Regulations and Civil Court Cases, 6/4/1943

Coal Crew at Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, Providing Heat for Residents During Cold Winter Months, 9/15/1942

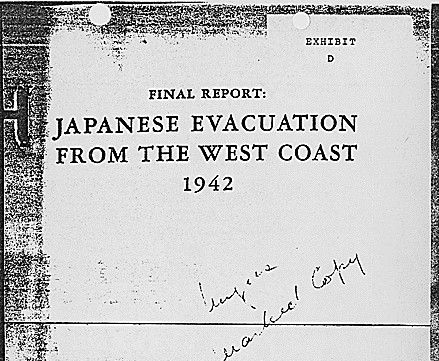

Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 – Written by General DeWitt, who Oversaw the Internment of Japanese-Americans, Providing a Favorable Overview of the "Evacuation Program"

This 10-minute film clip called "Japanese-Americans" (1945) comes from Army-Navy Screen Magazine , a biweekly film series for servicemen during World War II. It highlights the 100th Infantry Battalion, composed largely of Japanese-Americans.

This video clip shows President Ronald Reagan Giving Remarks and Signing the Japanese-American Internment Compensation Bill, 8/10/1988

Teaching Activity

In Japanese American Incarceration During World War II on DocsTeach students analyze a variety of documents and photographs to learn how the government justified the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, and how civil liberties were denied.

Additional Background Information

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had identified German, Italian, and Japanese aliens who were suspected of being potential enemy agents; and they were kept under surveillance. Following the attack at Pearl Harbor, government suspicion arose not only around aliens who came from enemy nations, but around all persons of Japanese descent, whether foreign born ( issei ) or American citizens ( nisei ). During congressional committee hearings, representatives of the Department of Justice raised logistical, constitutional, and ethical objections. Regardless, the task was turned over to the U.S. Army as a security matter.

The entire West Coast was deemed a military area and was divided into military zones. Executive Order 9066 authorized military commanders to exclude civilians from military areas. Although the language of the order did not specify any ethnic group, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command proceeded to announce curfews that included only Japanese Americans. Next, he encouraged voluntary evacuation by Japanese Americans from a limited number of areas; about seven percent of the total Japanese American population in these areas complied.

On March 29, 1942, under the authority of the executive order, DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 4, which began the forced evacuation and detention of Japanese-American West Coast residents on a 48-hour notice. Only a few days prior to the proclamation, on March 21, Congress had passed Public Law 503, which made violation of Executive Order 9066 a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in prison and a $5,000 fine.

Because of the perception of "public danger," all Japanese Americans within varied distances from the Pacific coast were targeted. Unless they were able to dispose of or make arrangements for care of their property within a few days, their homes, farms, businesses, and most of their private belongings were lost forever.

From the end of March to August, approximately 112,000 persons were sent to "assembly centers" – often racetracks or fairgrounds – where they waited and were tagged to indicate the location of a long-term "relocation center" that would be their home for the rest of the war. Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. There were no charges of disloyalty against any of these citizens, nor was there any vehicle by which they could appeal their loss of property and personal liberty.

"Relocation centers" were situated many miles inland, often in remote and desolate locales. Sites included Tule Lake and Manzanar in California; Gila River and Poston in Arizona; Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas, Minidoka in Idaho; Topaz in Utah; Heart Mountain in Wyoming; and Granada in Colorado. (Incarceration rates were significantly lower in the territory of Hawaii, where Japanese Americans made up over one-third of the population and their labor was needed to sustain the economy. However, martial law had been declared in Hawaii immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack, and the Army issued hundreds of military orders, some applicable only to persons of Japanese ancestry.)

In the "relocation centers" (also called "internment camps"), four or five families, with their sparse collections of clothing and possessions, shared tar-papered army-style barracks. Most lived in these conditions for nearly three years or more until the end of the war. Gradually some insulation was added to the barracks and lightweight partitions were added to make them a little more comfortable and somewhat private. Life took on some familiar routines of socializing and school. However, eating in common facilities, using shared restrooms, and having limited opportunities for work interrupted other social and cultural patterns. Persons who resisted were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake, CA, where dissidents were housed.

In 1943 and 1944, the government assembled a combat unit of Japanese Americans for the European theater. It became the 442d Regimental Combat Team and gained fame as the most highly decorated of World War II. Their military record bespoke their patriotism.

As the war drew to a close, "internment camps" were slowly evacuated. While some persons of Japanese ancestry returned to their hometowns, others sought new surroundings. For example, the Japanese-American community of Tacoma, WA, had been sent to three different centers; only 30 percent returned to Tacoma after the war. Japanese Americans from Fresno had gone to Manzanar; 80 percent returned to their hometown.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II sparked constitutional and political debate. During this period, three Japanese-American citizens challenged the constitutionality of the forced relocation and curfew orders through legal actions: Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Mitsuye Endo. Hirabayashi and Korematsu received negative judgments; but Mitsuye Endo, after a lengthy battle through lesser courts, was determined to be "loyal" and allowed to leave the Topaz, Utah, facility.

Justice Murphy of the Supreme Court expressed the following opinion in Ex parte Mitsuye Endo :

I join in the opinion of the Court, but I am of the view that detention in Relocation Centers of persons of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is not only unauthorized by Congress or the Executive but is another example of the unconstitutional resort to racism inherent in the entire evacuation program. As stated more fully in my dissenting opinion in Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu v. United States , 323 U.S. 214 , 65 S.Ct. 193, racial discrimination of this nature bears no reasonable relation to military necessity and is utterly foreign to the ideals and traditions of the American people.

In 1988, Congress passed, and President Reagan signed, Public Law 100-383 – the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 – that acknowledged the injustice of "internment," apologized for it, and provided a $20,000 cash payment to each person who was incarcerated.

One of the most stunning ironies in this episode of denied civil liberties was articulated by an internee who, when told that Japanese Americans were put in those camps for their own protection, countered "If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?"

A note on terminology: The historical primary source documents included on this page reflect the terminology that the government used at the time, such as alien , evacuation , relocation , relocation centers , internment , and Japanese (as opposed to Japanese American ).

- Rogerian Argument

The Rogerian argument, inspired by the influential psychologist Carl Rogers, aims to find compromise on a controversial issue.

If you are using the Rogerian approach your introduction to the argument should accomplish three objectives:

1. Introduce the author and work Usually, you will introduce the author and work in the first sentence:

Here is an example:

In Dwight Okita’s “In Response to Executive Order 9066,” the narrator addresses an inevitable by-product of war – racism.

The first time you refer to the author, refer to him or her by his or her full name. After that, refer to the author by last name only. Never refer to an author by his or her first name only.

2. Provide the audience a short but concise summary of the work to which you are responding Remember, your audience has already read the work you are responding to. Therefore, you do not need to provide a lengthy summary. Focus on the main points of the work to which you are responding and use direct quotations sparingly. Direct quotations work best when they are powerful and compelling.

3. State the main issue addressed in the work Your thesis, or claim, will come after you summarize the two sides of the issue.

The Introduction

The following is an example of how the introduction of a Rogerian argument can be written. The topic is racial profiling.

In Dwight Okita’s “In Response to Executive Order 9066,” the narrator — a young Japanese-American — writes a letter to the government, who has ordered her family into a relocation camp after Pearl Harbor. In the letter, the narrator details the people in her life, from her father to her best friend at school. Since the narrator is of Japanese descent, her best friend accuses her of “trying to start a war” (18). The narrator is seemingly too naïve to realize the ignorance of this statement, and tells the government that she asked this friend to plant tomato seeds in her honor. Though Okita’s poem deals specifically with World War II, the issue of race relations during wartime is still relevant. Recently, with the outbreaks of terrorism in the United States, Spain, and England, many are calling for racial profiling to stifle terrorism. The issue has sparked debate, with one side calling it racism and the other calling it common sense.

Once you have written your introduction, you must now show the two sides to the debate you are addressing. Though there are always more than two sides to a debate, Rogerian arguments put two in stark opposition to one another. Summarize each side, then provide a middle path. Your summary of the two sides will be your first two body paragraphs. Use quotations from outside sources to effectively illustrate the position of each side.

An outline for a Rogerian argument might look like this:

- Introduction

Since the goal of Rogerian argument is to find a common ground between two opposing positions, you must identify the shared beliefs or assumptions of each side. In the example above, both sides of the racial profiling issue want the U.S. A solid Rogerian argument acknowledges the desires of each side, and tries to accommodate both. Again, using the racial profiling example above, both sides desire a safer society, perhaps a better solution would focus on more objective measures than race; an effective start would be to use more screening technology on public transportation. Once you have a claim that disarms the central dispute, you should support the claim with evidence, and quotations when appropriate.

Quoting Effectively

Remember, you should quote to illustrate a point you are making. You should not, however, quote to simply take up space. Make sure all quotations are compelling and intriguing: Consider the following example. In “The Danger of Political Correctness,” author Richard Stein asserts that, “the desire to not offend has now become more important than protecting national security” (52). This statement sums up the beliefs of those in favor of profiling in public places.

The Conclusion

Your conclusion should:

- Bring the essay back to what is discussed in the introduction

- Tie up loose ends

- End on a thought-provoking note

The following is a sample conclusion:

Though the debate over racial profiling is sure to continue, each side desires to make the United States a safer place. With that goal in mind, our society deserves better security measures than merely searching a person who appears a bit dark. We cannot waste time with such subjective matters, especially when we have technology that could more effectively locate potential terrorists. Sure, installing metal detectors and cameras on public transportation is costly, but feeling safe in public is priceless.

Permission granted from Michael Franco at Writing Essay 4: Rogerian Argument

- Rogerian Argument. Authored by : Robin Parent. Provided by : Utah State University English Department. Project : USU Open CourseWare Initiative. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Table of Contents

Instructor Resources (Access Requires Login)

- Overview of Instructor Resources

An Overview of the Writing Process

- Introduction to the Writing Process

- Introduction to Writing

- Your Role as a Learner

- What is an Essay?

- Reading to Write

- Defining the Writing Process

- Videos: Prewriting Techniques

- Thesis Statements

- Organizing an Essay

- Creating Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Editing and Proofreading

- Matters of Grammar, Mechanics, and Style

- Peer Review Checklist

- Comparative Chart of Writing Strategies

Using Sources

- Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Formatting the Works Cited Page (MLA)

- Citing Paraphrases and Summaries (APA)

- APA Citation Style, 6th edition: General Style Guidelines

Definition Essay

- Definitional Argument Essay

- How to Write a Definition Essay

- Critical Thinking

- Video: Thesis Explained

- Effective Thesis Statements

- Student Sample: Definition Essay

Narrative Essay

- Introduction to Narrative Essay

- Student Sample: Narrative Essay

- "Shooting an Elephant" by George Orwell

- "Sixty-nine Cents" by Gary Shteyngart

- Video: The Danger of a Single Story

- How to Write an Annotation

- How to Write a Summary

- Writing for Success: Narration

Illustration/Example Essay

- Introduction to Illustration/Example Essay

- "She's Your Basic L.O.L. in N.A.D" by Perri Klass

- "April & Paris" by David Sedaris

- Writing for Success: Illustration/Example

- Student Sample: Illustration/Example Essay

Compare/Contrast Essay

- Introduction to Compare/Contrast Essay

- "Disability" by Nancy Mairs

- "Friending, Ancient or Otherwise" by Alex Wright

- "A South African Storm" by Allison Howard

- Writing for Success: Compare/Contrast

- Student Sample: Compare/Contrast Essay

Cause-and-Effect Essay

- Introduction to Cause-and-Effect Essay

- "Cultural Baggage" by Barbara Ehrenreich

- "Women in Science" by K.C. Cole

- Writing for Success: Cause and Effect

- Student Sample: Cause-and-Effect Essay

Argument Essay

- Introduction to Argument Essay

- "The Case Against Torture," by Alisa Soloman

- "The Case for Torture" by Michael Levin

- How to Write a Summary by Paraphrasing Source Material

- Writing for Success: Argument

- Student Sample: Argument Essay

- Grammar/Mechanics Mini-lessons

- Mini-lesson: Subjects and Verbs, Irregular Verbs, Subject Verb Agreement

- Mini-lesson: Sentence Types

- Mini-lesson: Fragments I

- Mini-lesson: Run-ons and Comma Splices I

- Mini-lesson: Comma Usage

- Mini-lesson: Parallelism

- Mini-lesson: The Apostrophe

- Mini-lesson: Capital Letters

- Grammar Practice - Interactive Quizzes

- De Copia - Demonstration of the Variety of Language

- Style Exercise: Voice

In Response to Executive Order 9066

By Dwight Okita

‘In Response to Executive Order 9066’ by Dwight Okita presents a letter written by a fourteen-year-old Japanese-American girl during World War II.

Dwight Okita

Nationality: American

Key Poem Information

Unlock more with Poetry +

Central Message: The personal toll that societal fear and prejudice can take on individuals.

Themes: Relationships , War

Speaker: A 14 year old Japanese-American girl

Emotions Evoked: Anxiety , Sadness

Poetic Form: Free Verse

Time Period: 20th Century

'In Response to Executive Order 9066' provides a deeply personal insight into the lives affected by the forced internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Poem Analyzed by Emma Baldwin

B.A. English (Minor: Creative Writing), B.F.A. Fine Art, B.A. Art Histories

The title of this poem refers to the executive order that led to the internment of Japanese Americans during the war. ‘In Response to Executive Order 9066’ is a contemporary poem written by Japanese-American poet and novelist Dwight Holden. His work, like this piece, usually focuses on the experiences of Japanese-American immigrants, gay men, and religion.

Explore In Response to Executive Order 9066

- 1 Summary

- 2 Structure and Form

- 3 Literary Devices

- 4 Detailed Analysis

- 6 Similar Poetry

Summary

‘In Response to Executive Order 9066’ by Dwight Okita describes her ordinary teenage life and emphasizes her American identity.

When the poem begins, she mentions packing for the relocation. She talks about her friendship with a white girl named Denise.

The poet conveys the shifting dynamics the two experience when Denise accuses the narrator of “giving secrets away to the Enemy.” The poem illustrates the personal and emotional effects of the internment on Japanese-American citizens.

Structure and Form

‘In Response to Executive Order 9066’ by Dwight Okita is a four-stanza poem divided into one five-line stanza , one eight-line stanza, one seven-line stanza, and a final five-line stanza, known as a quintain . It is also written in free verse , meaning that it doesn’t adhere to a specific rhyme scheme or meter , and the line lengths vary throughout the poem.

The structure is more akin to a personal letter or monologue, and this informality helps convey the young narrator’s voice .

Literary Devices

In this poem, the poet makes use of several literary devices. These include:

- Allusion : A reference to something outside the direct scope of the poem. In this case, the poet alludes to the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII.

- Symbolism : In addition to the tomato seeds, other elements, such as the galoshes, may be seen as symbols .

- Juxtaposition : This can be seen when the poet places contrasting elements close together. For example, pairing the girl’s bad spelling and messy room with the historical trauma of internment.

Detailed Analysis

Stanza one .

Dear Sirs: Of course I’ll come. I’ve packed my galoshes and three packets of tomato seeds. Denise calls them love apples. My father says where we’re going they won’t grow.

The first stanza starts in the form of a letter. The speaker uses a formal tone in these lines, referring to the “Sirs” who demand that her family relocate due to order 9066. It establishes the context of a letter and gives an immediate sense of the communication’s impersonal nature.

The poet’s speaker says, “Of course,” she’ll obey the command, suggesting the resignation or acceptance of the forced relocation. It may also signify the innocence of the narrator, who does not fully comprehend the gravity of the situation.

The three packets of tomato seeds introduce a rich symbol . Tomato seeds represent growth, hope, connection to home, and life before the internment. They may also symbolize the girl’s innocence and her attachment to small comforts.

This makes sense when the speaker’s father notes that the tomato seeds won’t “grow” where they’re going. They’re going somewhere devoid of hope, life, and prosperity.

Stanza Two

I am a fourteen-year-old girl with bad spelling (…) O’Connor, Ozawa. I know the back of Denise’s head very well.

In the second stanza of the poem, which is also the longest, the speaker describes herself as a “fourteen-year-old girl” who has bad spelling and a messy room. She’s a normal teenager who is disconnected from stereotypical cultural expectations. This is seen through the fact that she “always felt funny using chopsticks.”

The introduction of Denise as her best friend, a “white girl,” emphasizes the theme of multiculturalism. Their shared experiences and interest in boys reflect typical teenage friendships, another way that the poet is emphasizing how normal and relatable this girl is.

The mention of their last names, “O’Connor, Ozawa,” highlights their different ethnic backgrounds but also shows how they were paired together by mere alphabetical ordering. This is a way that the poet emphasizes the arbitrary ways that society groups people.

Stanza Three

I tell her she’s going bald. She tells me I copy on tests. (…) mouth shut?”

The speaker reveals in these lines that she thinks of Denise as her best friend. Although they bicker, she cares about her. She teases her friend, telling her that she’s going bald, while Denise accuses her of copying her answers.

The observation that Denise is sitting on the other side of the room, like lines three and four, signals a change in their relationship. She accuses her once-friend of “trying to start a war” and “giving secrets away to the Enemy,” things that she undoubtedly heard from her parents.

This is a poignant moment that captures the profound effect that war and propaganda can have on individual relationships.

Stanza Four

I didn’t know what to say. (…) she’d miss me.

The poem ends on a sad note, one that reemphasizes how naive the speaker is and how difficult this period in history was. The narrator’s response is gentle and thoughtful, serving as a strong contrast to Denise’s cruel words.

The act of giving Denise a packet of tomato seeds serves as a symbolic gesture. Previously, the seeds represented growth, hope, and connection. Here, they become a token of memory and continuity.

The poem ends with a hopeful statement, suggesting that Denise may eventually recognize her mistake and remember their friendship fondly. The gesture is filled with both sadness and hope. It reflects the complexity of human emotions and relationships during this time.

The purpose of this poem is to humanize a historical event by telling it from the perspective of a young girl. This invites readers to connect emotionally and understand the impact on individual lives.

Executive Order 9066, issued in 1942, authorized the forced relocation and internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. The poem gives voice to those affected by this historical event.

The characters are a 14-year-old Japanese-American girl who is innocent, thoughtful, and struggling to understand her forced relocation, Denise (the narrator ’s white best friend), and the narrator ’s father, whose voice is one of realism and understanding.

The main theme is the loss of innocence and the transformation of relationships under societal prejudice and fear. It explores how external forces can invade personal lives, altering perceptions and causing betrayal.

Similar Poetry

Readers who enjoyed this poem should also consider reading some related pieces. For example:

- ‘ Immigration ’ by Ali Alizadeh – is a captivating look at the positives, negatives, and the emotional and mental toll that immigration takes.

- ‘ Immigrant Blues ’ by Li-Young Lee – describes an immigrant’s bewilderment with the idea of internalizing a second language other than their own.

- ‘ Lorikeets ‘ by Peter Skrzynecki – is about the conditions under which the poet and his family were forced to migrate to Australia.

Poetry + Review Corner

20th century, relationships, world war two (wwii).

Home » Dwight Okita » In Response to Executive Order 9066

About Emma Baldwin

Join the poetry chatter and comment.

Exclusive to Poetry + Members

Join Conversations

Share your thoughts and be part of engaging discussions.

Expert Replies

Get personalized insights from our Qualified Poetry Experts.

Connect with Poetry Lovers

Build connections with like-minded individuals.

Access the Complete PDF Guide of this Poem

Poetry + PDF Guides are designed to be the ultimate PDF Guides for poetry. The PDF Guide consists of a front cover, table of contents, with the full analysis, including the Poetry+ Review Corner and numerically referenced literary terms, plus much more.

Get the PDF Guide

Experts in Poetry

Our work is created by a team of talented poetry experts, to provide an in-depth look into poetry, like no other.

Cite This Page

Baldwin, Emma. "In Response to Executive Order 9066 by Dwight Okita". Poem Analysis , https://poemanalysis.com/dwight-okita/in-response-to-executive-order-9066/ . Accessed 17 September 2024.

Help Center

Request an Analysis

(not a member? Join now)

Poem PDF Guides

PDF Learning Library

Beyond the Verse Podcast

Poetry Archives

Poetry Explained

Poet Biographies

Useful Links

Poem Explorer

Poem Generator

Poem Solutions Limited, International House, 36-38 Cornhill, London, EC3V 3NG, United Kingdom

Get this Poem Analysis as an Offline Resource

Poetry+ PDF Guides are designed to be the ultimate PDF Guides for poetry. The PDF Guide contains everything to understand poetry.

(and discover the hidden secrets to understanding poetry)

Get PDFs to Help You Learn Poetry

250+ Reviews

Download Poetry PDF Guides

Complete Poetry PDF Guide

Perfect Offline Resource

Covers Everything You Need to Know

One-pager 'snapshot' PDF

Offline Resource

Gateway to deeper understanding

Top of page

Collection Japanese-American Internment Camp Newspapers, 1942 to 1946

December 7, 1941.

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, leading the U.S. to enter World War II.

February 19, 1942

President Franklin D. Roosevelts signs Executive Order 9066, providing for the exclusion of any person from any area at the discretion of the military.

March 2, 1942

General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, divides parts of the West Coast into Military Area 1 and Military Area 2, from which people of Japanese ancestry would be excluded.

March 18, 1942

The War Relocation Authority is established to oversee the relocation of Japanese-Americans and relocation centers.

March 24, 1942

The first Civilian Exclusion Order is issued by the Army, giving families one week to prepare for removal from their homes.

April 11, 1942

Manzanar Free Press begins publication at the Manzanar Relocation Center in California.

June 2, 1942

All Japanese in Military Area 1 in California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona have been removed into Army custody.

December 17, 1944

Relocation orders are revoked and exclusion is lifted, effective January 2, 1945.

December 1945

All camps besides Tule Lake are closed.

The camp at Tule Lake closes.

August 10, 1988

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 is passed by Congress and signed by President Ronald Reagan. The Act apologizes for internment and provides for reparations to survivors.

Mericans and Response to Executive Order 9066

Dwight Okita and Sandra Cisneros are two American writers who have addressed the issue of Executive Order 9066 in their work. Dwight Okita’s poem “In the Bag” is a response to the executive order, while Sandra Cisneros’ short story “Eleven” also addresses the topic.

Dwight Okita was born in California to Japanese parents. He was interned with his family at Manzanar during World War II. In “In the Bag,” Okita imagines what it would have been like if his family had been forced to leave their home without being able to take anything with them. The poem reflects on the loss of personal belongings and how they can represent one’s identity.

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago to a Mexican father and a Mexican-American mother. She is best known for her novel The House on Mango Street, which tells the story of a young Latina girl growing up in Chicago. In “Eleven,” Cisneros addresses the issue of bullying and how it can make one feel powerless. The protagonist, Rachel, is an eleven-year-old girl who is teased by her classmates about her height. She feels alone and different from everyone else, but she ultimately learns to embrace her unique identity.

Writers such as Dwight Okita and Sandra Cisneros have been influenced by American culture. “Response to Executive Order 9066” by Dwight Okita, and “Mericans” by Sandra Cisnerosa are two examples of writers who have utilized the idea of American identity.

In his poem, Okita explores the notion of American identity by focusing on the connection between two pals from different racial backgrounds. The place you’re from and how you look has nothing to do with what it means to be an American in these poems.

In “Response to Executive Order 9066”, Dwight Okita examines the cost of being Japanese-American during World War II. The speaker in the poem reflects on his experience being sent to an internment camp, and how thisevent changed his view of what it means to be American. In the poem, Okita writes:

“We were American then,/before we were yellow or Jap or nisei./We were young and common and strong,/and swore allegiance to the stars and stripes./We had never seen a man die…”

This excerpt from the poem demonstrates how the speaker’s experience in an internment camp led him to question his American identity. He recalls that before he was interned, he considered himself to be American first and foremost. However, after being treated like a criminal by his own government, he begins to question what it really means to be American.

Sandra Cisneros’ poem “Mericans” also explores the concept of American identity. In the poem, Cisneros writes about a young girl who is struggling to find her place in the world. The girl is of Mexican descent, but she was born in the United States and considers herself to be American.

However, she doesn’t feel like she fits in with either culture. She is not Mexican enough for the Mexicans, and she is not American enough for the Americans. The girl in the poem feels like she is stuck between two cultures and doesn’t quite belong to either one.

Both Dwight Okita and Sandra Cisneros use their poems to explore the concept of American identity. They both demonstrate that where you’re from and how you look doesn’t define what it means to be American. American identity is something that is fluid and ever-changing. It is something that is defined by each individual person.

In response to “Mericans,” Michelle, the daughter, appears to despise her entire family as she names them one by one. For example, she refers to her uncle Uncle Fat-face and aunt Auntie Light-skin as such. In American society, childhood is a carefree time, but this girl appears to be having difficulties with her sense of self because she claims that she is the only daughter who does not want on Sundays.

She is ashamed of her family, and she does not want to be like them. When the family moves to California, she is excited because she thinks she will finally fit in. However, she soon realizes that she is different from everyone else there too. She is not like the other girls at school, and she does not feel like she belongs.

The poem ends with the girl saying that she is “not American”, and this seems to be her final realization that she will never truly feel like she belongs anywhere. She is caught between two cultures, and neither one feels like home.

This poem speaks to the experience of many immigrants who come to the United States. They often find that they are not really accepted as American, and they can never truly feel at home here. This poem also speaks to the issue of assimilation. The girl in the poem is trying to assimilate, but she just doesn’t fit in. She is not like her family, and she is not like the people in her community. This poem highlights the challenges that many immigrants face when they come to the United States.

The horrible grandmother is pushing her to not want to be from her culture as a result of the pressure she puts on her. When the “awful grandma” prays for “Mericans” and represents her dislike of the United States, the author develops the American Identity theme.

The character Dwight Okita also plays a role in the American Identity theme because he is from a different culture, but he eventually assimilates to the “Merican” culture. Sandra Cisneros develops the theme of American Identity by having the daughter want to find her own identity and not the one her grandmother is pushing on her. Dwight Okita also plays a role in developing this theme because he is from a different culture, but he eventually assimilates to the “Merican” culture.

The girl’s name is Leslie and she is a 6th grader. She lives in St. Louis, Missouri with her mother and father, who works long hours. The narrative describes how the protagonist’s life was greatly altered when her family sought refuge from racial prejudice at an internment camp during World War II.

As we continue reading, we see how severely Leslie is impacted as she claims that her closest friend is a white girl named Denise. Her best friend has affected her because of the difference in their family customs. When it came time for the little girl to go to an internment camp, she had a quarrel with Denise and was told to stop talking by Denise.

The little girl then says “I wanted to tell her I was American too, but I didn’t know how” (Okita). The little girl is now forced to confront her identity. She doesn’t want to be different, she just wants to be like everyone else and have the same opportunities.

In the story, the little girl’s father tries to tell her that being different is what makes America great. The father says “That’s what makes this country great. People from all over the world coming together and making something new, something beautiful” (Okita). Even though the little girl’s father tries to make her see the beauty in diversity, she still feels lost and confused.

It isn’t until later on in the story when the little girl reads a poem by Sandra Cisneros that she finally begins to understand. The poem is called ” Mericans” and it is about a Mexican-American girl who is trying to find her place in the world. The little girl realizes that she is just like the girl in the poem, and that it is okay to be different. In fact, it is what makes America great.

More Essays

- Eleven By Sandra Cisneros Essay

- Imagery In Eleven By Sandra Cisneros

- Advantages Of The Unitary Executive Theory Essay

- Creative Response To The Raven Essay

- Literary Devices In Eleven By Sandra Cisneros

- Camp Manzanar Research Paper

- Explain Your Response: Breaking Away From My Family

- Professional Counseling Executive Summary

- Eleven By Sandra Cisneros Analysis Essay

- A Materialist Response

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066"

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Works Cited

- Cisneros, Sandra. "Mericans." Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories , Random House, 1991.

- Okita, Dwight. "Response to Executive Order 9066." No-No Boy , Mina Harker Publishing, 1976.

Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066". (2020, Jun 02). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/in-both-mericans-and-response-21471-new-essay

"Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066"." StudyMoose , 2 Jun 2020, https://studymoose.com/in-both-mericans-and-response-21471-new-essay

StudyMoose. (2020). Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066" . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/in-both-mericans-and-response-21471-new-essay [Accessed: 18 Sep. 2024]

"Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066"." StudyMoose, Jun 02, 2020. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://studymoose.com/in-both-mericans-and-response-21471-new-essay

"Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066"," StudyMoose , 02-Jun-2020. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/in-both-mericans-and-response-21471-new-essay. [Accessed: 18-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2020). Comparing "Mericans" and "Response to Executive Order 9066" . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/in-both-mericans-and-response-21471-new-essay [Accessed: 18-Sep-2024]

- Comparing Fate and Transformation in Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Pages: 4 (1096 words)

- Comparing and contrasting Achilles and other warriors Pages: 4 (1174 words)

- Comparing and Contrasting Country Lovers and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty Pages: 6 (1532 words)

- Comparing and contrasting Silver Blaze and Finger Man Pages: 3 (731 words)

- Comparing and Contrasting Liberal, Socialist, and Radical Feminism Pages: 7 (1869 words)

- Comparing and Contrast of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Pages: 11 (3258 words)

- Comparing the Similarities and Differences Between North End and East Boston Pages: 12 (3377 words)

- Shakespeare and Webster's Tragic Heroes: Comparing Hamlet and Bosola Pages: 8 (2193 words)

- Comparing Fire and Ice by Frost and The Day They Came For Our House by Mattera Pages: 7 (1956 words)

- Comparing and Contrasting Warming Her Pearls and Epithalamium: A Poetic Analysis Pages: 5 (1278 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Executive Order 9066 was issued by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. It granted the secretary of war and his commanders the power to exclude people from 'military areas.'. While no group or location was specified in the order, it was applied to virtually all Japanese Americans on the West Coast.

Japanese-Americans were called Nisei. This executive order affected over 117,000 Japanese-Americans from both generations. Thousands of people lost their homes and businesses due to "failure to pay taxes". EO 9066 was widely controversial. This order stayed in place until President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9742 on June 25, 1946.

EnlargeDownload Link Citation: Executive Order 9066, February 19, 1942; General Records of the Unites States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives. View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog View Transcript Issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, this order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast ...

This map shows the extent of the exclusion zone Japanese Americans were forced to leave and the locations of the 10 internment camps to which they were sent. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. On Feb. 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, setting in motion the internment of more than 120,000 Japanese American citizens.

Executive Order 9066. A girl detained in Arkansas walks to school in 1943. Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national ...

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, initiating a controversial World War II policy with lasting consequences for Japanese Americans. The document ...

On Feb. 19, 1942 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed "Executive Order 9066," which paved the way for the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese-Americans from the West Coast during World War II. Families were forced to leave their homes and businesses and move inland to camps, sometimes thousands of miles from home.

Critical Essays Executive Order 9066. The paperwork which set this story in motion is a barely comprehensible, bureaucratic order signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House on February 19, 1942. Overall, the wording reiterates a constitutional fact — that the U.S. President functions as commander in chief of the military and exerts ...

Overview. Executive Order 9066 was a piece of legislation issued by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II on February 19, 1942. The order granted the secretary of war and his commanders the power to declare particular sections of the country as military areas and to force the removal of people deemed to be "enemy aliens ...

There was little organized opposition to Executive Order 9066 and the subsequent incarceration of Japanese Americans. A small group of progressive church organizations that included the American Friends Service Committee mounted protests and Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas circulated a petition to void FDR's order.

In-Class Essay: Executive Order 9066. The overreach of executive power by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Executive Order 9066 demonstrates how executive orders are an abuse of power by the President of the United States and that they are deliberately designed to toe the line of what is constitutionally allowed. They have been deemed ...

In February 1942, just two months later, President Roosevelt, as commander-in-chief, issued Executive Order 9066 that resulted in the internment of Japanese Americans. The order authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to evacuate all persons deemed a threat from the West Coast to internment camps, that the government called ...

Executive Order No. 9066 The President Executive Order Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas. Stat. 655 (U.S.C., Title 50, Sec. 104); Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War ...

Japanese-Americans were called Nisei. This executive order affected over 117,000 Japanese-Americans from both generations. Thousands of people lost their homes and businesses due to "failure to pay taxes". EO 9066 was widely controversial. This order stayed in place until President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9742 on June 25, 1946.

If you are using the Rogerian approach your introduction to the argument should accomplish three objectives: 1. Introduce the author and work. Usually, you will introduce the author and work in the first sentence: Here is an example: In Dwight Okita's "In Response to Executive Order 9066," the narrator addresses an inevitable by-product ...

Poem Analyzed by Emma Baldwin. B.A. English (Minor: Creative Writing), B.F.A. Fine Art, B.A. Art Histories. The title of this poem refers to the executive order that led to the internment of Japanese Americans during the war. 'In Response to Executive Order 9066' is a contemporary poem written by Japanese-American poet and novelist Dwight ...

TOPIC: Executive Order 9066 (using primary and secondary source materials) LESSON DESIGNED FOR: Grades 11-12 TIME: Part 1: 50 min. - Small group primary source study (Recommended PRE-VISIT lesson for use before visiting Go For Broke National Education Center exhibition) Part 2: 2-3 hours - Group research and presentations Part 3: 60 min ...

Murphy's assertion that the main purpose of Executive Order 9066 was the "legalization of racism" is the only reasonable interpretation of the actions taken by the United States government during the war, and one can only hope that in our current war on terror, the government can learn from its past mistakes and shy away from actions which may ...

President Franklin D. Roosevelts signs Executive Order 9066, providing for the exclusion of any person from any area at the discretion of the military. March 2, 1942 General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, divides parts of the West Coast into Military Area 1 and Military Area 2, from which people of Japanese ancestry would ...

This essay will compare and contrast the development of the theme in each work, highlighting the specific literary devices and techniques employed by the authors. In "Response to Executive Order 9066," Okita skillfully employs imagery and symbolism to convey the theme of injustice and its impact on individuals. The author describes the ...

Dwight Okita and Sandra Cisneros are two American writers who have addressed the issue of Executive Order 9066 in their work. Dwight Okita's poem "In the Bag" is a response to the executive order, while Sandra Cisneros' short story "Eleven" also addresses the topic. Dwight Okita was born in California to Japanese parents.

Essay Sample: Prompt: In a five-paragraph literary analysis essay, explain how each author develops the common theme by referencing specific literary devices and ... In 'Response to Executive Order 9066,' Okita chooses to use different methods while still conveying a similar theme. By using the direct thoughts of the narrator, it allows the ...

On December 7th, 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the Executive Order 9066. The President issued this order following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. This order gave the military permission to circumvent the constitutional safeguards of American citizens in the name of national defense. After enforcing this order 120,000 Japanese people ...