- How to Write a Strong Psychology Essay Conclusion with an Example

A conclusion is an essential component of a psychology essay. It restates the main argument of your essay and helps to a lasting impression your reader. Let us dive in and learn how to create impactful conclusions within a short period without having to use a language model.

Table of Contents

How to Write a Strong Psychology Essay Conclusion

Introduction.

In the structure of a psychology essay, a conclusion is an essential component. Firstly, it serves to restate the main points that were covered in the essay using the shortest number of words possible. Secondly, it presents an opportunity to develop recommendations and reflections on the implications of your argument for psychology practice. A conclusion should not have in-text citations, as no new information is presented. Here, as a student, you are supposed to synthesize the main points, showing your comprehensive understanding of the topic. In this short post, I am going to show you how to write a conclusion of a psychology essay. I will discuss the recommended length, the steps you should follow and provide an example.

What is the length of a psychology essay conclusion?

The conclusion length of a psychology essay depends on the length of your whole paper. Whilst answering this question, Robin Turner, who was a former English lecturer at Bilkent University, states, “You don’t want your conclusion to be more than a fifth of your essay,” which translates to 20% of your essay. However, in my undergraduate and master’s psychology university education, the rule of thumb was that your conclusion should be 10% of the total word count limit. That is the case for most universities globally. We normally advise that you keep it at 10% of your essay’s total word count.

What are the steps for writing a conclusion for a psychology essay?

Restate your specific thesis statement. This involves linking back to the question that your essay was seeking to answer. There is an ongoing debate if you should use the phrase “in conclusion.” While answering this question, Ali Mullin, who is an instructor at Louisiana State University terms ending your conclusion with the phrase as being reductionist. She suggested the use of such styles as “[idea 1], [idea 2], and [idea 3] all illustrate [concept/argument]. Considering these [ideas] synthesizes/realizes/proves my point that [argument]. In the future, I hope to see [idea]”.

Summarize and synthesize the main points that were discussed in the essay, showing great mastery of the topic that you discussed.

Present your conclusion from the point of view of the conclusion that you provided, linking it to the main argument of your essay.

Finally, provide a broad statement that suggests how your conclusion impacts, is related, or is essential in practice.

For more information on h0w to write other parts of a psychology essay, check out our comprehensive guide .

Concisely, human beings use both the exemplar and prototype theories as framework for categorizing concepts. Even though both theories are essential, they are varied in their manner of application since the prototypes are appropriate for simple and hierarchical categories. On other hand, exemplars are suitable for flat and nuanced domains. Cultural differences in relation to various concepts such as classification of fruits and leadership shape categorization affecting prototypes and how conclusions are made in relation to specific examples. By harnessing both prototype and exemplar perspectives, people can optimize learning and creativity, drawing upon existing knowledge to navigate new terrain.

The first sentence restates the thesis statement.

The second and third sentences synthesizes the main points that were developed in the paper.

The last sentence is a broad statement regarding the argument that the essay makes.

It is worth noting that we discourage the use of language models in your psychology essay. However, you can use AI specifically Gemini to develop your conclusion.

We highly recommend seeking help from our psychology assignment experts .

Affordable Psychology Essay Writing Service

Provide your paper details using our intuitive form and find out how much our psychology essay help will cost you. Note that the price of your order will depend on the number of pages, deadline, and the academic level. If your place your order with us early enough, the price will be much lower, and our experts will have enough time to craft an excellent paper for you. We are currently offering 25% OFF discount for not only new customers but also new ones.

- Formatting (MLA, APA, Chicago, custom, etc.)

- Title page & bibliography

- 24/7 customer support

- Amendments to your paper when they are needed

- Chat with your writer

- 275 word/double-spaced page

- 12 point Arial/Times New Roman

- Double, single, and custom spacing

We have a strict policy against plagiarism. We always screen delivered psychology assignments using Turnitin before you receive them because it is the most used and trusted software by universities globally. Your university will use Turnitin AI detector to screen your written assignment. Our writers understand that using AI to produce content is frowned upon and anyone caught doing that is expelled from our platform.

Our service is General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and U.S. Data Privacy Protection Laws compliant. Therefore, your personal information such as credit cards and personal identification information such as email and phone number will not be shared with third parties. Even our writers do not have access to this information.

You can stay rest assured that you will get value for your money. In case your plans change and feel that you no longer need our services, you will get a refund as soon as possible.

How to Order

- 1 Fill the Order Form Fill out the details of your paper using our user-friendly and intuitive order form. The details should include the academic level, the type of paper, the number of words, your preferred deadline, and the writer level that best suits your needs and expectations. After providing all the necessary details, including additional materials, leave it to us at this point.

- 2 We find you an expert Our 24/7-available support team will receive your paid order. We will choose you the most suitable expert for your psychology paper. We consider the following factors in our writer selection criteria: (a) the academic level of the order, (b) the subject of your order, and (c) the urgency. The writer will start working on your order as soon as possible. We have a culture of delivering papers ahead of time without compromising quality, demonstrating our imppecable commitment towards customer satisfaction.

- 3 You get the paper done Immediately the customer delivers the order, you will receive a notification email containing the final paper. You can also login to your portal to download additional files, such as the plagiarism report and the AI-free content screenshot.

Samples of Psychology Essay Writing Help From Our Advanced Writers

Check out some psychology essay pieces from our best writers before you decide to buy a psychology paper from us. They will help you better understand the kind of psychology essay help we offer.

- Lab Report Psychology Lab Report Example: Brain Cerebral Hemispheres Laterality- Dowel Rod Experiment Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Case study Analysis of Common Alcohol Screening Tools Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Coursework Critique of Western Approaches to Psychological Science Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Term paper Challenges of Supporting Mental Health Patients in the Community Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Term paper To what extent does Social Psychology Contribute to our Understanding of Current Events Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Research paper Patient Centered Care and Dementia Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Research paper Age and Belongingness Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Prolonged Grief Disorder Undergrad. (yrs 1-2) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Five-Factor Personality Model vs The Six-Factor Personality Model Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Counselling Session and Person-Centered Approach Master's Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Psychosocial Development Theories Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Student Bias Against Female Instructors Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Personal Construct Theory Undergrad. (yrs 1-2) Psychology APA View this sample

- Essay (any type) Can Personality Predict a Person's Risk of Psychological Distress Undergrad. (yrs 3-4) Psychology APA View this sample

Get your own paper from top experts

Benefits of our psychology essay writing service.

We offer more than more than customized psychology papers. Here are more of our greatest perks.

- Confidentiality and Privacy Your identifying information, such as email address and phone number will not be shared with any third party under whatever circumstance.

- Timely Updates We will send you regular updates regarding the progress of your order at any given time.

- Free Originality Reports Our service strives to give our customers plagiarism-free papers, 100% human-written.

- 100% Human Content Guaranteed Besides giving you a free plagiarism/Turnitin report, we will also provide you with a TurnItIn AI screenshot.

- Unlimited Revisions Ask improvements to your completed paper unlimited times.

- 24/7 Support We typically reply within a few minutes at any time of the day or day of week.

Take your studies to the next level with our experienced Psychology Experts

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Before you write your essay, it’s important to analyse the task and understand exactly what the essay question is asking. Your lecturer may give you some advice – pay attention to this as it will help you plan your answer.

Next conduct preliminary reading based on your lecture notes. At this stage, it’s not crucial to have a robust understanding of key theories or studies, but you should at least have a general “gist” of the literature.

After reading, plan a response to the task. This plan could be in the form of a mind map, a summary table, or by writing a core statement (which encompasses the entire argument of your essay in just a few sentences).

After writing your plan, conduct supplementary reading, refine your plan, and make it more detailed.

It is tempting to skip these preliminary steps and write the first draft while reading at the same time. However, reading and planning will make the essay writing process easier, quicker, and ensure a higher quality essay is produced.

Components of a Good Essay

Now, let us look at what constitutes a good essay in psychology. There are a number of important features.

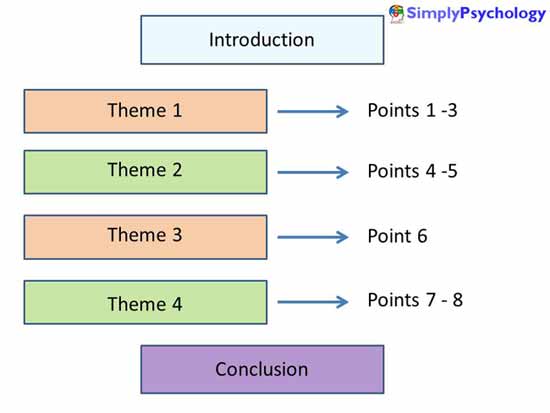

- Global Structure – structure the material to allow for a logical sequence of ideas. Each paragraph / statement should follow sensibly from its predecessor. The essay should “flow”. The introduction, main body and conclusion should all be linked.

- Each paragraph should comprise a main theme, which is illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

- Knowledge and Understanding – recognize, recall, and show understanding of a range of scientific material that accurately reflects the main theoretical perspectives.

- Critical Evaluation – arguments should be supported by appropriate evidence and/or theory from the literature. Evidence of independent thinking, insight, and evaluation of the evidence.

- Quality of Written Communication – writing clearly and succinctly with appropriate use of paragraphs, spelling, and grammar. All sources are referenced accurately and in line with APA guidelines.

In the main body of the essay, every paragraph should demonstrate both knowledge and critical evaluation.

There should also be an appropriate balance between these two essay components. Try to aim for about a 60/40 split if possible.

Most students make the mistake of writing too much knowledge and not enough evaluation (which is the difficult bit).

It is best to structure your essay according to key themes. Themes are illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

Choose relevant points only, ones that most reveal the theme or help to make a convincing and interesting argument.

Knowledge and Understanding

Remember that an essay is simply a discussion / argument on paper. Don’t make the mistake of writing all the information you know regarding a particular topic.

You need to be concise, and clearly articulate your argument. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences.

Each paragraph should have a purpose / theme, and make a number of points – which need to be support by high quality evidence. Be clear why each point is is relevant to the argument. It would be useful at the beginning of each paragraph if you explicitly outlined the theme being discussed (.e.g. cognitive development, social development etc.).

Try not to overuse quotations in your essays. It is more appropriate to use original content to demonstrate your understanding.

Psychology is a science so you must support your ideas with evidence (not your own personal opinion). If you are discussing a theory or research study make sure you cite the source of the information.

Note this is not the author of a textbook you have read – but the original source / author(s) of the theory or research study.

For example:

Bowlby (1951) claimed that mothering is almost useless if delayed until after two and a half to three years and, for most children, if delayed till after 12 months, i.e. there is a critical period.

Maslow (1943) stated that people are motivated to achieve certain needs. When one need is fulfilled a person seeks to fullfil the next one, and so on.

As a general rule, make sure there is at least one citation (i.e. name of psychologist and date of publication) in each paragraph.

Remember to answer the essay question. Underline the keywords in the essay title. Don’t make the mistake of simply writing everything you know of a particular topic, be selective. Each paragraph in your essay should contribute to answering the essay question.

Critical Evaluation

In simple terms, this means outlining the strengths and limitations of a theory or research study.

There are many ways you can critically evaluate:

Methodological evaluation of research

Is the study valid / reliable ? Is the sample biased, or can we generalize the findings to other populations? What are the strengths and limitations of the method used and data obtained?

Be careful to ensure that any methodological criticisms are justified and not trite.

Rather than hunting for weaknesses in every study; only highlight limitations that make you doubt the conclusions that the authors have drawn – e.g., where an alternative explanation might be equally likely because something hasn’t been adequately controlled.

Compare or contrast different theories

Outline how the theories are similar and how they differ. This could be two (or more) theories of personality / memory / child development etc. Also try to communicate the value of the theory / study.

Debates or perspectives

Refer to debates such as nature or nurture, reductionism vs. holism, or the perspectives in psychology . For example, would they agree or disagree with a theory or the findings of the study?

What are the ethical issues of the research?

Does a study involve ethical issues such as deception, privacy, psychological or physical harm?

Gender bias

If research is biased towards men or women it does not provide a clear view of the behavior that has been studied. A dominantly male perspective is known as an androcentric bias.

Cultural bias

Is the theory / study ethnocentric? Psychology is predominantly a white, Euro-American enterprise. In some texts, over 90% of studies have US participants, who are predominantly white and middle class.

Does the theory or study being discussed judge other cultures by Western standards?

Animal Research

This raises the issue of whether it’s morally and/or scientifically right to use animals. The main criterion is that benefits must outweigh costs. But benefits are almost always to humans and costs to animals.

Animal research also raises the issue of extrapolation. Can we generalize from studies on animals to humans as their anatomy & physiology is different from humans?

The PEC System

It is very important to elaborate on your evaluation. Don’t just write a shopping list of brief (one or two sentence) evaluation points.

Instead, make sure you expand on your points, remember, quality of evaluation is most important than quantity.

When you are writing an evaluation paragraph, use the PEC system.

- Make your P oint.

- E xplain how and why the point is relevant.

- Discuss the C onsequences / implications of the theory or study. Are they positive or negative?

For Example

- Point: It is argued that psychoanalytic therapy is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority.

- Explain: Because psychoanalytic therapy involves talking and gaining insight, and is costly and time-consuming, it is argued that it is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority. Evidence suggests psychoanalytic therapy works best if the client is motivated and has a positive attitude.

- Consequences: A depressed client’s apathy, flat emotional state, and lack of motivation limit the appropriateness of psychoanalytic therapy for depression.

Furthermore, the levels of dependency of depressed clients mean that transference is more likely to develop.

Using Research Studies in your Essays

Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation.

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding.

- If you comment on what the studies shows, and what it supports and challenges about the theory in question, this shows evaluation.

Writing an Introduction

It is often best to write your introduction when you have finished the main body of the essay, so that you have a good understanding of the topic area.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your introduction.

Ideally, the introduction should;

Identify the subject of the essay and define the key terms. Highlight the major issues which “lie behind” the question. Let the reader know how you will focus your essay by identifying the main themes to be discussed. “Signpost” the essay’s key argument, (and, if possible, how this argument is structured).

Introductions are very important as first impressions count and they can create a h alo effect in the mind of the lecturer grading your essay. If you start off well then you are more likely to be forgiven for the odd mistake later one.

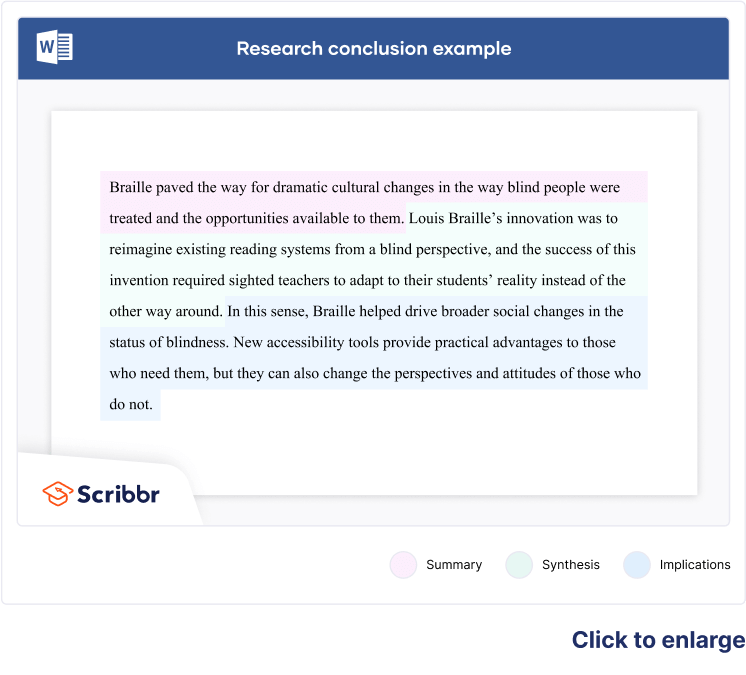

Writing a Conclusion

So many students either forget to write a conclusion or fail to give it the attention it deserves.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your conclusion.

Ideally the conclusion should summarize the key themes / arguments of your essay. State the take home message – don’t sit on the fence, instead weigh up the evidence presented in the essay and make a decision which side of the argument has more support.

Also, you might like to suggest what future research may need to be conducted and why (read the discussion section of journal articles for this).

Don”t include new information / arguments (only information discussed in the main body of the essay).

If you are unsure of what to write read the essay question and answer it in one paragraph.

Points that unite or embrace several themes can be used to great effect as part of your conclusion.

The Importance of Flow

Obviously, what you write is important, but how you communicate your ideas / arguments has a significant influence on your overall grade. Most students may have similar information / content in their essays, but the better students communicate this information concisely and articulately.

When you have finished the first draft of your essay you must check if it “flows”. This is an important feature of quality of communication (along with spelling and grammar).

This means that the paragraphs follow a logical order (like the chapters in a novel). Have a global structure with themes arranged in a way that allows for a logical sequence of ideas. You might want to rearrange (cut and paste) paragraphs to a different position in your essay if they don”t appear to fit in with the essay structure.

To improve the flow of your essay make sure the last sentence of one paragraph links to first sentence of the next paragraph. This will help the essay flow and make it easier to read.

Finally, only repeat citations when it is unclear which study / theory you are discussing. Repeating citations unnecessarily disrupts the flow of an essay.

Referencing

The reference section is the list of all the sources cited in the essay (in alphabetical order). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms every time you cite/refer to a name (and date) of a psychologist you need to reference the original source of the information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites, then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

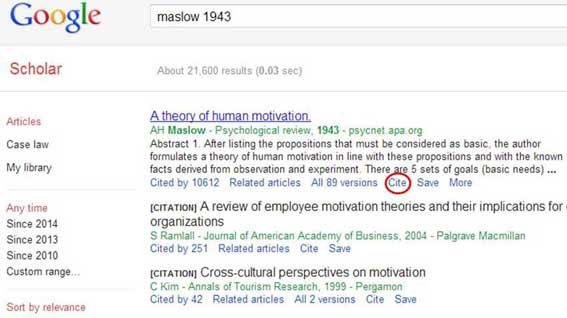

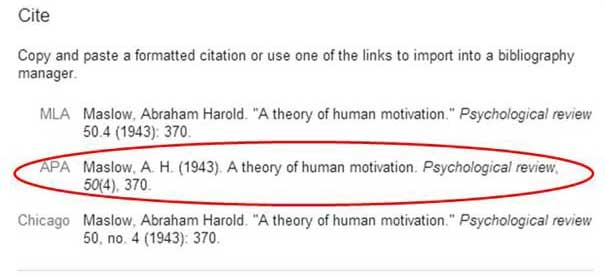

A simple way to write your reference section is use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

What this handout is about

This handout discusses some of the common writing assignments in psychology courses, and it presents strategies for completing them. The handout also provides general tips for writing psychology papers and for reducing bias in your writing.

What is psychology?

Psychology, one of the behavioral sciences, is the scientific study of observable behaviors, like sleeping, and abstract mental processes, such as dreaming. Psychologists study, explain, and predict behaviors. Because of the complexity of human behaviors, researchers use a variety of methods and approaches. They ask questions about behaviors and answer them using systematic methods. For example, to understand why female students tend to perform better in school than their male classmates, psychologists have examined whether parents, teachers, schools, and society behave in ways that support the educational outcomes of female students to a greater extent than those of males.

Writing in psychology

Writing in psychology is similar to other forms of scientific writing in that organization, clarity, and concision are important. The Psychology Department at UNC has a strong research emphasis, so many of your assignments will focus on synthesizing and critically evaluating research, connecting your course material with current research literature, and designing and carrying out your own studies.

Common assignments

Reaction papers.

These assignments ask you to react to a scholarly journal article. Instructors use reaction papers to teach students to critically evaluate research and to synthesize current research with course material. Reaction papers typically include a brief summary of the article, including prior research, hypotheses, research method, main results, and conclusions. The next step is your critical reaction. You might critique the study, identify unresolved issues, suggest future research, or reflect on the study’s implications. Some instructors may want you to connect the material you are learning in class with the article’s theories, methodology, and findings. Remember, reaction papers require more than a simple summary of what you have read.

To successfully complete this assignment, you should carefully read the article. Go beyond highlighting important facts and interesting findings. Ask yourself questions as you read: What are the researchers’ assumptions? How does the article contribute to the field? Are the findings generalizable, and to whom? Are the conclusions valid and based on the results? It is important to pay attention to the graphs and tables because they can help you better assess the researchers’ claims.

Your instructor may give you a list of articles to choose from, or you may need to find your own. The American Psychological Association (APA) PsycINFO database is the most comprehensive collection of psychology research; it is an excellent resource for finding journal articles. You can access PsycINFO from the E-research tab on the Library’s webpage. Here are the most common types of articles you will find:

- Empirical studies test hypotheses by gathering and analyzing data. Empirical articles are organized into distinct sections based on stages in the research process: introduction, method, results, and discussion.

- Literature reviews synthesize previously published material on a topic. The authors define or clarify the problem, summarize research findings, identify gaps/inconsistencies in the research, and make suggestions for future work. Meta-analyses, in which the authors use quantitative procedures to combine the results of multiple studies, fall into this category.

- Theoretical articles trace the development of a specific theory to expand or refine it, or they present a new theory. Theoretical articles and literature reviews are organized similarly, but empirical information is included in theoretical articles only when it is used to support the theoretical issue.

You may also find methodological articles, case studies, brief reports, and commentary on previously published material. Check with your instructor to determine which articles are appropriate.

Research papers

This assignment involves using published research to provide an overview of and argument about a topic. Simply summarizing the information you read is not enough. Instead, carefully synthesize the information to support your argument. Only discuss the parts of the studies that are relevant to your argument or topic. Headings and subheadings can help guide readers through a long research paper. Our handout on literature reviews may help you organize your research literature.

Choose a topic that is appropriate to the length of the assignment and for which you can find adequate sources. For example, “self-esteem” might be too broad for a 10- page paper, but it may be difficult to find enough articles on “the effects of private school education on female African American children’s self-esteem.” A paper in which you focus on the more general topic of “the effects of school transitions on adolescents’ self-esteem,” however, might work well for the assignment.

Designing your own study/research proposal

You may have the opportunity to design and conduct your own research study or write about the design for one in the form of a research proposal. A good approach is to model your paper on articles you’ve read for class. Here is a general overview of the information that should be included in each section of a research study or proposal:

- Introduction: The introduction conveys a clear understanding of what will be done and why. Present the problem, address its significance, and describe your research strategy. Also discuss the theories that guide the research, previous research that has been conducted, and how your study builds on this literature. Set forth the hypotheses and objectives of the study.

- Methods: This section describes the procedures used to answer your research questions and provides an overview of the analyses that you conducted. For a research proposal, address the procedures that will be used to collect and analyze your data. Do not use the passive voice in this section. For example, it is better to say, “We randomly assigned patients to a treatment group and monitored their progress,” instead of “Patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group and their progress was monitored.” It is acceptable to use “I” or “we,” instead of the third person, when describing your procedures. See the section on reducing bias in language for more tips on writing this section and for discussing the study’s participants.

- Results: This section presents the findings that answer your research questions. Include all data, even if they do not support your hypotheses. If you are presenting statistical results, your instructor will probably expect you to follow the style recommendations of the American Psychological Association. You can also consult our handout on figures and charts . Note that research proposals will not include a results section, but your instructor might expect you to hypothesize about expected results.

- Discussion: Use this section to address the limitations of your study as well as the practical and/or theoretical implications of the results. You should contextualize and support your conclusions by noting how your results compare to the work of others. You can also discuss questions that emerged and call for future research. A research proposal will not include a discussion section. But you can include a short section that addresses the proposed study’s contribution to the literature on the topic.

Other writing assignments

For some assignments, you may be asked to engage personally with the course material. For example, you might provide personal examples to evaluate a theory in a reflection paper. It is appropriate to share personal experiences for this assignment, but be mindful of your audience and provide only relevant and appropriate details.

Writing tips for psychology papers

Psychology is a behavioral science, and writing in psychology is similar to writing in the hard sciences. See our handout on writing in the sciences . The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association provides an extensive discussion on how to write for the discipline. The Manual also gives the rules for psychology’s citation style, called APA. The Library’s citation tutorial will also introduce you to the APA style.

Suggestions for achieving precision and clarity in your writing

- Jargon: Technical vocabulary that is not essential to understanding your ideas can confuse readers. Similarly, refrain from using euphemistic phrases instead of clearer terms. Use “handicapped” instead of “handi-capable,” and “poverty” instead of “monetarily felt scarcity,” for example.

- Anthropomorphism: Anthropomorphism occurs when human characteristics are attributed to animals or inanimate entities. Anthropomorphism can make your writing awkward. Some examples include: “The experiment attempted to demonstrate…,” and “The tables compare…” Reword such sentences so that a person performs the action: “The experimenter attempted to demonstrate…” The verbs “show” or “indicate” can also be used: “The tables show…”

- Verb tenses: Select verb tenses carefully. Use the past tense when expressing actions or conditions that occurred at a specific time in the past, when discussing other people’s work, and when reporting results. Use the present perfect tense to express past actions or conditions that did not occur at a specific time, or to describe an action beginning in the past and continuing in the present.

- Pronoun agreement: Be consistent within and across sentences with pronouns that refer to a noun introduced earlier (antecedent). A common error is a construction such as “Each child responded to questions about their favorite toys.” The sentence should have either a plural subject (children) or a singular pronoun (his or her). Vague pronouns, such as “this” or “that,” without a clear antecedent can confuse readers: “This shows that girls are more likely than boys …” could be rewritten as “These results show that girls are more likely than boys…”

- Avoid figurative language and superlatives: Scientific writing should be as concise and specific as possible. Emotional language and superlatives, such as “very,” “highly,” “astonishingly,” “extremely,” “quite,” and even “exactly,” are imprecise or unnecessary. A line that is “exactly 100 centimeters” is, simply, 100 centimeters.

- Avoid colloquial expressions and informal language: Use “children” rather than “kids;” “many” rather than “a lot;” “acquire” rather than “get;” “prepare for” rather than “get ready;” etc.

Reducing bias in language

Your writing should show respect for research participants and readers, so it is important to choose language that is clear, accurate, and unbiased. The APA sets forth guidelines for reducing bias in language: acknowledge participation, describe individuals at the appropriate level of specificity, and be sensitive to labels. Here are some specific examples of how to reduce bias in your language:

- Acknowledge participation: Use the active voice to acknowledge the subjects’ participation. It is preferable to say, “The students completed the surveys,” instead of “The experimenters administered surveys to the students.” This is especially important when writing about participants in the methods section of a research study.

- Gender: It is inaccurate to use the term “men” when referring to groups composed of multiple genders. See our handout on gender-inclusive language for tips on writing appropriately about gender.

- Race/ethnicity: Be specific, consistent, and sensitive with terms for racial and ethnic groups. If the study participants are Chinese Americans, for instance, don’t refer to them as Asian Americans. Some ethnic designations are outdated or have negative connotations. Use terms that the individuals or groups prefer.

- Clinical terms: Broad clinical terms can be unclear. For example, if you mention “at risk” in your paper, be sure to specify the risk—“at risk for school failure.” The same principle applies to psychological disorders. For instance, “borderline personality disorder” is more precise than “borderline.”

- Labels: Do not equate people with their physical or mental conditions or categorize people broadly as objects. For example, adjectival forms like “older adults” are preferable to labels such as “the elderly” or “the schizophrenics.” Another option is to mention the person first, followed by a descriptive phrase— “people diagnosed with schizophrenia.” Be careful using the label “normal,” as it may imply that others are abnormal.

- Other ways to reduce bias: Consistently presenting information about the socially dominant group first can promote bias. Make sure that you don’t always begin with men followed by other genders when writing about gender, or whites followed by minorities when discussing race and ethnicity. Mention differences only when they are relevant and necessary to understanding the study. For example, it may not be important to indicate the sexual orientation of participants in a study about a drug treatment program’s effectiveness. Sexual orientation may be important to mention, however, when studying bullying among high school students.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. n.d. “Frequently Asked Questions About APA Style®.” APA Style. Accessed June 24, 2019. https://apastyle.apa.org/learn/faqs/index .

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Landrum, Eric. 2008. Undergraduate Writing in Psychology: Learning to Tell the Scientific Story . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Write a Great Psychology Essay

Categories Psychology Education

Writing a great psychology essay takes skill. You need good research skills to provide an adequate empirical background. You also need to put your analytical skills to work to evaluate the research and then build a coherent argument. If you are not used to writing psychology essays, it can be a little challenging at first (especially if you are also learning how to use APA format).

Remember, the skill of writing an exceptional psychology essay lies not only in presenting information, but also in synthesizing and explaining it effectively. If you need to write a psychology essay for a class, here are some tips to help you get started.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Craft a strong thesis statement highlighting the main points of your psychology essay.

- Incorporate research studies to support arguments and critically evaluate their validity and reliability.

- Structure the essay with a clear introduction, focused body paragraphs, and a compelling conclusion.

- Include critical analysis by evaluating research methodologies, strengths, weaknesses, and ethical considerations.

What to Include in an APA Format Essay

To craft a great psychology essay, it’s important to make sure you follow the right format. While your instructor may have specific instructions, the typical format for an essay includes the following sections:

- The title page

- The abstract

- The introduction

- The main body

- The reference section

Mastering the key components of a psychology essay is vital for crafting a compelling and academically sound piece of writing. To start, a good introduction sets the stage for your essay, providing a clear overview of what will be discussed.

Moving on to the main body, each paragraph should focus on a main theme, supported by evidence from research studies published in peer-reviewed journals. It’s pivotal to critically evaluate these studies, considering their validity, reliability, and limitations to strengthen your arguments.

Incorporating research studies not only adds credibility to your essay but also demonstrates a deep understanding of theoretical perspectives in psychology.

The Structure of a Psychology Essay

Each section of a psychology essay should also follow a specific format:

The Title Page

The title page is the first impression of your essay, and it should be formatted according to APA guidelines. It typically includes:

- The title of your essay : Make sure it’s concise, descriptive, and gives the reader an idea of its content.

- Your name : Place your full name below the title.

- Institutional affiliation : This usually refers to your university or college.

- Course number and name : Include the course for which the essay is being written.

- Instructor’s name : Write the name of your instructor.

- Due date : Indicate the date when the essay is due.

The Abstract

The abstract is a brief summary of your essay, typically around 150-250 words. It should provide a snapshot of the main points and findings. Key elements include:

- Research topic : Briefly describe what your essay is about.

- Research questions : Outline the main questions your essay addresses.

- Methodology : Summarize the methods used to gather information or conduct research.

- Results : Highlight the key findings.

- Conclusion : Provide a concise conclusion or the implications of your findings.

The Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for your essay, providing context and outlining the main points. It should include:

- Hook : Start with an interesting fact, quote, or anecdote to grab the reader’s attention.

- Background information : Provide necessary context or background information on your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state the main argument or purpose of your essay.

- Overview of structure : Briefly outline the structure of your essay to give the reader a roadmap.

The Main Body

The main body is the core of your essay, where you present your arguments, evidence, and analysis. It should be well-organized and divided into sections with subheadings if necessary. Each section should include:

- Topic sentences : Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that introduces the main idea.

- Evidence : Provide evidence to support your arguments, such as data, quotes, or studies.

- Analysis : Analyze the evidence and explain how it supports your thesis.

- Transitions : Use transitions to ensure a smooth flow between paragraphs and sections.

The Reference Section

The reference section is crucial for giving credit to the sources you used and for allowing readers to locate the sources themselves. It should follow APA format and include:

- Alphabetical order : List all sources alphabetically by the author’s last name.

- Proper citation format : Follow APA guidelines for formatting each type of source (books, articles, websites, etc.).

- Hanging indent : Ensure that each reference entry has a hanging indent.

By following these guidelines, you can ensure that your psychology essay is well-structured, informative, and adheres to APA format.

Using Research in Your Psychology Essay

To strengthen the arguments in your psychology essay, it’s essential to incorporate relevant research studies that provide credibility and depth to your analysis. Utilizing research studies not only enhances the validity of your points but also demonstrates a deeper understanding of the topic at hand.

When integrating research into your essay, remember to include citations for each study referenced to give proper credit and allow readers to explore the sources further.

It is also important to evaluate the research studies you include to assess their validity, reliability, and any ethical considerations involved. This helps you determine the trustworthiness of the findings and whether they align with your argument.

Be sure to discuss any ethical concerns, such as participant deception or potential harm, and showcase a thoughtful approach to utilizing research in your essay.

Analyzing the Research Critically

When writing a psychology essay, using high-quality research sources and analyzing them critically is crucial. This not only strengthens your arguments but also ensures the credibility and reliability of your work. Here are some guidelines to help you critically analyze sources and use them appropriately:

Evaluating the Credibility of Sources

- Authorship : Check the credentials of the author. Are they an expert in the field? Do they have relevant qualifications or affiliations with reputable institutions?

- Publication Source : Determine where the research was published. Peer-reviewed journals, academic books, and respected organizations are considered reliable sources.

- Date of Publication : Ensure the research is current and up-to-date. In psychology, recent studies are often more relevant as they reflect the latest findings and theories.

- Citations and References : Look at how often the source is cited by other scholars. A frequently cited source is generally more credible.

Assessing the Quality of the Research

- Research Design and Methodology : Evaluate the research design. Is it appropriate for the study’s aims? Consider the sample size, controls, and methods used.

- Data Analysis : Check how the data was analyzed. Are the statistical methods sound and appropriate? Were the results interpreted correctly?

- Bias and Limitations : Identify any potential biases or limitations in the study. Authors should acknowledge these in their discussion.

Synthesizing Information from Multiple Sources

- Comparing Findings : Compare findings from different sources to identify patterns, trends, or discrepancies. This can help you understand the broader context and the range of perspectives on your topic.

- Integrating Evidence : Integrate evidence from various sources to build a comprehensive argument. Use multiple pieces of evidence to support each point or counterpoint in your essay.

Citing Sources Appropriately

- In-Text Citations : Follow APA guidelines for in-text citations. Include the author’s last name and the year of publication (e.g., Smith, 2020).

- Direct Quotes and Paraphrasing : When directly quoting, use quotation marks and provide a page number. For paraphrasing, ensure you rephrase the original text significantly and still provide an in-text citation.

- Reference List : Include a complete reference list at the end of your essay, formatted according to APA guidelines.

Using Sources to Support Your Argument

- Relevance : Ensure each source directly relates to your thesis or the specific point you are discussing. Irrelevant information can distract from your argument.

- Strength of Evidence : Use the strongest and most persuasive evidence available. Prioritize high-quality, peer-reviewed studies over less reliable sources.

- Balance : Present a balanced view by including evidence that supports and opposes your thesis. Acknowledging counterarguments demonstrates thorough research and critical thinking.

By critically analyzing research sources and using them appropriately, you can enhance the quality and credibility of your psychology essay. This approach ensures that your arguments are well-supported, your analysis is thorough, and your work adheres to academic standards.

Putting the Finishing Touches on Your Psychology Essay

Once you have a basic grasp of the topic and have written a rough draft of your psychology essay, the next step is to polish it up and ensure it is ready to turn in. To perfect your essay structure, consider the following:

- Make sure your topic is well-defined: Make sure your essay topic is specific and focused to provide a clear direction for your writing.

- Check that you are highlighting a main point in each paragraph: Commence each paragraph with a topic sentence that encapsulates the main idea you’ll discuss.

- Revise and refine your first draft: Take the time to review and refine your initial draft, guaranteeing that each section flows logically into the next and that your arguments are well-supported. ( Tip: Ask a friend of classmate to read through it to catch any typos or errors you might have missed. )

- Check your APA format : Use the APA publication manual to double-check that all your sources are cited and referenced correctly.

Creating an amazing psychology essay requires a compelling introduction, evidence-based arguments, a strong thesis statement, critical analysis, and a well-structured essay.

By incorporating research from peer-reviewed journals, evaluating studies for validity and reliability, and considering differing viewpoints and ethical considerations, you can craft a powerful and insightful piece that showcases your understanding of the topic.

With attention to detail and logical flow, your psychology essay will captivate and inform your readers effectively.

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Writing a psychology essay can be daunting, because of the constant changes in understanding and differing perspectives that exist in the field. However, if you follow our tips and guidelines you are guaranteed to produce a first-class, high quality psychology essay.

Types of Psychology essay

Psychology essays can come in a range of formats:

- Compare and contrast.

For example:

- Compare the benefits of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with psychoanalysis on patients with schizophrenia.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of family therapy for children of drug addicts.

- CBT is the most effective form of treatment for those struggling with mental illness. Discuss

Once you understand what is being asked of you, and thus the focus of your essay, you can move on to identifying how to structure your work. In all cases the broad structure is similar – an introduction – body section and conclusion. Furthermore, in all cases, your work, and any statements you make should be made using only verifiable, credible sources that should be referenced clearly at the end of your work. To support you in delivering a premium psychology essay, we have indicated a general structure for you to follow.

Introduction

The most important thing about your introduction is it just that. An introduction. It should be short, captivating and hook your reader into wanting to carry on. A good introduction introduces a few key points about the topic so that the reader knows the subject of your paper and its background.

You should also include a thesis statement which describes your intent and perspective on the matter. The statement comes from first identifying a question you wish to ask, for example, “how does CBT differ from psychoanalysis in treating schizophrenics”. This will then enable you to identify a clear statement such as “CBT is more effective in treating schizophrenics than psychoanalysis”. In effect, a captivating introduction sets out what you will be saying in your essay, clearly, concisely, and objectively.

Body of the Essay

The body of the essay is where you make all your relevant points and undertake a dissection of the central themes of your work in the topic area. Note when undertaking a compare and contrast essay it is a good practice to indicate all the similarities and then the differences to ensure a smooth coherent flow.

For each point you make, use a separate paragraph, and ensure that any statements you make are backed up by credible evidence and properly referenced sources. In an evaluation essay, you should indicate the analysis undertaken to make the judgement you have, again backed by credible sources. Discussive psychology essays require you to state your point and then debate it with pros and cons for each side.

Overall, in the body section, you body text should be focused on providing valuable insights and evaluation of the topic and enable you to demonstrate deductive reasoning (“as a result of x… it can be indicated that”) and evidence based analysis (“although x indicates that y, a suggests an alternative view based on…”). Following a logical flow with one point per paragraph ensures the reader is able to follow your thinking process and eventually draw the same conclusions.

Furthermore, it is important when writing a psychology essay to examine a wide range of sources, that cover both sides of a topic or phenomenon. Without demonstrating a wide-ranging knowledge of the diversity of perspectives, you cannot be objective in evaluating a subject area.

In addition, you should recognise that not all your readers may be familiar with psychological terms or acronyms so these need to be explained briefly and concisely the first time they are used. Furthermore, you should avoid definitive statements, because psychology is constantly evolving so do not use phrases such as “this proves…”, instead use terms such as “this is consistent with work by…” or “this supports x’s view that…”. It is also not appropriate to use the first person (“I”), even when expressing opinions, always use the third person and where possible the past tense.

As with the introduction, the conclusion should hold the reader, and crystallise all the arguments and points made into an overall summation of your views. This summation should be in line with your thesis statement which has to be restated here and leave no room for unanswered questions. Your aim is to reaffirm that the points you have made in your body text sum up and provide a clear answer to the task of the psychology essay – whether this compare and contrast, discussion, or evaluation.

Key Phrases for a Psychology Essay

- Previous work in the area has suggested that…

- However, prior studies did not consider…

- In this paper it is therefore argued that…

- The significance of this view is that…

- In light of this indication, there is a potential that…

- In order to understand x, it is necessary to also recognise that…

- Similarly, it has been suggested that…

- Furthermore, additional evidence from x indicates that…

- Conversely, x suggests that…

- Similarly, the indications from … are that…

- That being said, it is also evident that…

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Tips for Writing Psychology Papers

Hero Images / Getty Images

Writing in psychology is formal, concise, and straightforward. When writing a psychology paper, avoid using metaphors, anecdotes, or narrative. Your paper should be well-cited and the point should be clear. In almost all cases, you will need to structure your paper in a specific way and follow the rules of APA format.

Learn more about writing in psychology and how to write a psychology paper.

The Importance of Writing in Psychology

Writing is important in psychology because the study and practice of psychology involves complex concepts. Writing is an important way to note observations, communicate new ideas, and support theories.

Most psychology courses require a significant amount of writing, including essays, case studies, research reports, and other papers . Start by viewing each class assignment as an opportunity to learn and practice. Check out resources offered by your school, such as tutors or writing labs, and learn more about the different types of psychology writing.

The following resources offer tips, guidelines, and advice on how to write psychology papers. If you are struggling with writing a psychology paper, following some of the guidelines below may help.

Basic Tips for Writing a Psychology Paper

If you have never written a psychology paper before, you need to start with the basics. Psychology writing is much like other types of writing, but most instructors will have special requirements for each assignment.

When writing a psychology paper, you will be expected to follow a few specific style guidelines. Some important tips to keep in mind include:

- Back up your words and ideas with evidence. Your work should be well-cited using evidence from the scientific literature. Avoid expressing your opinion or using examples from your own life.

- Use clear, concise language. Get directly to the point and make sure you are making logical connections between your arguments and conclusions and the evidence you cite.

- Avoid literary devices. Metaphors, anecdotes, and other literary devices you may have used in other types of writing aren't appropriate when you are writing a psychology paper.

- Use the correct format. Most psychology writing uses APA style, but your instructor may have additional formatting requirements.

- Check the rubric. Before you start a psychology paper, you'll need to learn more about what you should write about, how you should structure your paper, and what type of sources you should use. Always check the grading rubric for an assignment before you begin writing and brush up on the basics.

Types of Psychology Writing

There are a few different types of psychology papers you may be asked to write. Some examples and how to write them are listed below.

How to Write a Psychology Case Study

Students taking courses in abnormal psychology , child development , or psychotherapy will often be expected to write a case study on an individual—either real or imagined. Case studies vary somewhat, but most include a detailed history of the client, a description of the presenting problem, a diagnosis, and a discussion of possible treatments.

This type of paper can be both challenging and interesting. You will get a chance to explore an individual in great depth and find insights into their behaviors and motivations. Before you begin your assignment, learn more about how to write a psychology case study .

How to Write a Psychology Lab Report

Lab reports are commonly assigned in experimental or research-based psychology courses. The structure of a lab report is very similar to that of a professional journal article, so reading a few research articles is a good way to start learning more about the basic format of a lab report.

There are some basic rules to follow when writing a psychology lab report. Your report should provide a clear and concise overview of the experiment, research, or study you conducted. Before you begin working on your paper, read more about how to write a psychology lab report .

How to Write a Psychology Critique Paper

Psychology critique papers are often required in psychology courses, so you should expect to write one at some point in your studies. Your professor may expect you to provide a critique on a book, journal article , or psychological theory .

Students sometimes find that writing a critique can actually be quite challenging. How can you prepare for this type of assignment? Start by reading these tips and guidelines on how to write a psychology critique paper .

Remember to Edit Your Psychology Paper

Before you turn in any type of psychology writing, it is vital to proofread and edit your work for errors, typos, and grammar. Do not just rely on your computer's spellchecker to do the job! Always read thoroughly through your paper to remove mistakes and ensure that your writing flows well and is structured logically.

Finally, always have another person read your work to spot any mistakes you may have missed. After you have read something so many times, it can become difficult to spot your own errors. Getting a fresh set of eyes to read through it can be very helpful. Plus, your proofreader can ask questions and point out areas that might not be clear to the reader.

Know the Rules of APA Format

Not learning APA format is a mistake that costs points for many students. APA format is the official style of the American Psychological Association and is used in many different types of science writing, especially the social sciences. Before you hand in any writing assignment, always double-check your page format, in-text citations, and references for correct APA format. If you need directions or examples, check out this guide to APA format .

A Word From Verywell

Writing psychology papers is an important part of earning a degree in psychology. Even non-majors often find themselves writing such papers when taking general education psychology classes. Fortunately, paying attention to the directions provided by your instructor, familiarizing yourself with APA style, and following some basic guidelines for different types of psychology papers can make the process much easier.

Levitt HM. Reporting qualitative research in psychology: How to meet APA style journal article reporting standards . American Psychological Association; 2020. doi:10.1037/0000179-000

Willemsen J, Della Rosa E, Kegerreis S. Clinical case studies in psychoanalytic and psychodynamic treatment . Front Psychol . 2017;8:108. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00108

Klein RM, Saint-Aubin J. What a simple letter-detection task can tell us about cognitive processes in reading . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2016;25(6):417-424. doi:10.1177/0963721416661173

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on October 30, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on April 13, 2023.

- Restate the problem statement addressed in the paper

- Summarize your overall arguments or findings

- Suggest the key takeaways from your paper

The content of the conclusion varies depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument through engagement with sources .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: restate the problem, step 2: sum up the paper, step 3: discuss the implications, research paper conclusion examples, frequently asked questions about research paper conclusions.

The first task of your conclusion is to remind the reader of your research problem . You will have discussed this problem in depth throughout the body, but now the point is to zoom back out from the details to the bigger picture.

While you are restating a problem you’ve already introduced, you should avoid phrasing it identically to how it appeared in the introduction . Ideally, you’ll find a novel way to circle back to the problem from the more detailed ideas discussed in the body.

For example, an argumentative paper advocating new measures to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture might restate its problem as follows:

Meanwhile, an empirical paper studying the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues might present its problem like this:

“In conclusion …”

Avoid starting your conclusion with phrases like “In conclusion” or “To conclude,” as this can come across as too obvious and make your writing seem unsophisticated. The content and placement of your conclusion should make its function clear without the need for additional signposting.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Having zoomed back in on the problem, it’s time to summarize how the body of the paper went about addressing it, and what conclusions this approach led to.

Depending on the nature of your research paper, this might mean restating your thesis and arguments, or summarizing your overall findings.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

In an argumentative paper, you will have presented a thesis statement in your introduction, expressing the overall claim your paper argues for. In the conclusion, you should restate the thesis and show how it has been developed through the body of the paper.

Briefly summarize the key arguments made in the body, showing how each of them contributes to proving your thesis. You may also mention any counterarguments you addressed, emphasizing why your thesis holds up against them, particularly if your argument is a controversial one.

Don’t go into the details of your evidence or present new ideas; focus on outlining in broad strokes the argument you have made.

Empirical paper: Summarize your findings

In an empirical paper, this is the time to summarize your key findings. Don’t go into great detail here (you will have presented your in-depth results and discussion already), but do clearly express the answers to the research questions you investigated.

Describe your main findings, even if they weren’t necessarily the ones you expected or hoped for, and explain the overall conclusion they led you to.

Having summed up your key arguments or findings, the conclusion ends by considering the broader implications of your research. This means expressing the key takeaways, practical or theoretical, from your paper—often in the form of a call for action or suggestions for future research.

Argumentative paper: Strong closing statement

An argumentative paper generally ends with a strong closing statement. In the case of a practical argument, make a call for action: What actions do you think should be taken by the people or organizations concerned in response to your argument?

If your topic is more theoretical and unsuitable for a call for action, your closing statement should express the significance of your argument—for example, in proposing a new understanding of a topic or laying the groundwork for future research.

Empirical paper: Future research directions

In a more empirical paper, you can close by either making recommendations for practice (for example, in clinical or policy papers), or suggesting directions for future research.

Whatever the scope of your own research, there will always be room for further investigation of related topics, and you’ll often discover new questions and problems during the research process .

Finish your paper on a forward-looking note by suggesting how you or other researchers might build on this topic in the future and address any limitations of the current paper.

Full examples of research paper conclusions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

While the role of cattle in climate change is by now common knowledge, countries like the Netherlands continually fail to confront this issue with the urgency it deserves. The evidence is clear: To create a truly futureproof agricultural sector, Dutch farmers must be incentivized to transition from livestock farming to sustainable vegetable farming. As well as dramatically lowering emissions, plant-based agriculture, if approached in the right way, can produce more food with less land, providing opportunities for nature regeneration areas that will themselves contribute to climate targets. Although this approach would have economic ramifications, from a long-term perspective, it would represent a significant step towards a more sustainable and resilient national economy. Transitioning to sustainable vegetable farming will make the Netherlands greener and healthier, setting an example for other European governments. Farmers, policymakers, and consumers must focus on the future, not just on their own short-term interests, and work to implement this transition now.

As social media becomes increasingly central to young people’s everyday lives, it is important to understand how different platforms affect their developing self-conception. By testing the effect of daily Instagram use among teenage girls, this study established that highly visual social media does indeed have a significant effect on body image concerns, with a strong correlation between the amount of time spent on the platform and participants’ self-reported dissatisfaction with their appearance. However, the strength of this effect was moderated by pre-test self-esteem ratings: Participants with higher self-esteem were less likely to experience an increase in body image concerns after using Instagram. This suggests that, while Instagram does impact body image, it is also important to consider the wider social and psychological context in which this usage occurs: Teenagers who are already predisposed to self-esteem issues may be at greater risk of experiencing negative effects. Future research into Instagram and other highly visual social media should focus on establishing a clearer picture of how self-esteem and related constructs influence young people’s experiences of these platforms. Furthermore, while this experiment measured Instagram usage in terms of time spent on the platform, observational studies are required to gain more insight into different patterns of usage—to investigate, for instance, whether active posting is associated with different effects than passive consumption of social media content.

If you’re unsure about the conclusion, it can be helpful to ask a friend or fellow student to read your conclusion and summarize the main takeaways.

- Do they understand from your conclusion what your research was about?

- Are they able to summarize the implications of your findings?

- Can they answer your research question based on your conclusion?

You can also get an expert to proofread and feedback your paper with a paper editing service .

The conclusion of a research paper has several key elements you should make sure to include:

- A restatement of the research problem

- A summary of your key arguments and/or findings

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

No, it’s not appropriate to present new arguments or evidence in the conclusion . While you might be tempted to save a striking argument for last, research papers follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the results and discussion sections if you are following a scientific structure). The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, April 13). Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing a research paper introduction | step-by-step guide, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, checklist: writing a great research paper, what is your plagiarism score.

4 Chapter 1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the first chapter of this textbook has provided you with a glimpse into the multifaceted nature of the field of psychology. We have explored the fundamental question of “What is Psychology?” and have discussed its diverse subfields and applications. Moreover, we have delved into the rich history of psychology, acknowledging both its achievements and its ugliness, such as psychology’s contribution to eugenics and its failure to recognize the intellectual potential of BIPOC people and women. We have highlighted the transformative efforts of social justice activists within the discipline. As you consider becoming a psychology major or potential careers in psychology, it is important to recognize the profound impact psychologists can have on individuals and society as a whole. By studying the human mind and behavior, we can contribute to understanding, supporting, and advocating for the well-being of others. With this knowledge, we hope that you will embrace opportunities to make a positive difference and foster social change.

Introduction to Psychology (A critical approach) Copyright © 2021 by Rose M. Spielman; Kathryn Dumper; William Jenkins; Arlene Lacombe; Marilyn Lovett; and Marion Perlmutter is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition (2000)

Chapter: 10 conclusions, 10 conclusions.

The pace at which science proceeds sometimes seems alarmingly slow, and impatience and hopes both run high when discussions turn to issues of learning and education. In the field of learning, the past quarter century has been a period of major research advances. Because of the many new developments, the studies that resulted in this volume were conducted to appraise the scientific knowledge base on human learning and its application to education. We evaluated the best and most current scientific data on learning, teaching, and learning environments. The objective of the analysis was to ascertain what is required for learners to reach deep understanding, to determine what leads to effective teaching, and to evaluate the conditions that lead to supportive environments for teaching and learning.

A scientific understanding of learning includes understanding about learning processes, learning environments, teaching, sociocultural processes, and the many other factors that contribute to learning. Research on all of these topics, both in the field and in laboratories, provides the fundamental knowledge base for understanding and implementing changes in education.

This volume discusses research in six areas that are relevant to a deeper understanding of students’ learning processes: the role of prior knowledge in learning, plasticity and related issues of early experience upon brain development, learning as an active process, learning for understanding, adaptive expertise, and learning as a time-consuming endeavor. It reviews research in five additional areas that are relevant to teaching and environments that support effective learning: the importance of social and cultural contexts, transfer and the conditions for wide application of learning, subject matter uniqueness, assessment to support learning, and the new educational technologies.

LEARNERS AND LEARNING

Development and learning competencies.

Children are born with certain biological capacities for learning. They can recognize human sounds; can distinguish animate from inanimate objects; and have an inherent sense of space, motion, number, and causality. These raw capacities of the human infant are actualized by the environment surrounding a newborn. The environment supplies information, and equally important, provides structure to the information, as when parents draw an infant’s attention to the sounds of her or his native language.

Thus, developmental processes involve interactions between children’s early competencies and their environmental and interpersonal supports. These supports serve to strengthen the capacities that are relevant to a child’s surroundings and to prune those that are not. Learning is promoted and regulated by the children’s biology and their environments. The brain of a developing child is a product, at the molecular level, of interactions between biological and ecological factors. Mind is created in this process.

The term “development” is critical to understanding the changes in children’s conceptual growth. Cognitive changes do not result from mere accretion of information, but are due to processes involved in conceptual reorganization. Research from many fields has supplied the key findings about how early cognitive abilities relate to learning. These include the following:

“Privileged domains:” Young children actively engage in making sense of their worlds. In some domains, most obviously language, but also for biological and physical causality and number, they seem predisposed to learn.

Children are ignorant but not stupid: Young children lack knowledge, but they do have abilities to reason with the knowledge they understand.

Children are problem solvers and, through curiosity, generate questions and problems: Children attempt to solve problems presented to them, and they also seek novel challenges. They persist because success and understanding are motivating in their own right.

Children develop knowledge of their own learning capacities— metacognition—very early. This metacognitive capacity gives them the ability to plan and monitor their success and to correct errors when necessary.

Children’ natural capabilities require assistance for learning: Children’s early capacities are dependent on catalysts and mediation. Adults play a critical role in promoting children’s curiosity and persistence by directing children’s attention, structuring their experiences, supporting their

learning attempts, and regulating the complexity and difficulty of levels of information for them.