Advertisement

Supported by

Immortal Beloved

By Jeremy Denk

- July 31, 2014

- Share full article

In the show “30 Rock,” there was a running joke about tragedy. A character appears, reveals her tearful past, then brightly adds, “They made a Lifetime movie about me” — the credential of an absurdly pathetic story with a redemptive payoff. Of all the great composers’ lives, Ludwig van Beethoven’s seems the most made for Lifetime. The curtain opens on a difficult childhood: an abusive alcoholic father, a boy genius mocked for his dark skin. He survives, makes his way to Vienna for fame and fortune — only to be stricken by (gasp) deafness. In addition, we have impossible passions for mysterious beloveds, side themes of class struggle, freedom, individuality, the backdrop of Napoleonic conquest and a score (what a score!) surging with alternating storminess and tenderness. Beethoven’s story is almost too good to be true, and almost too bad to be television.

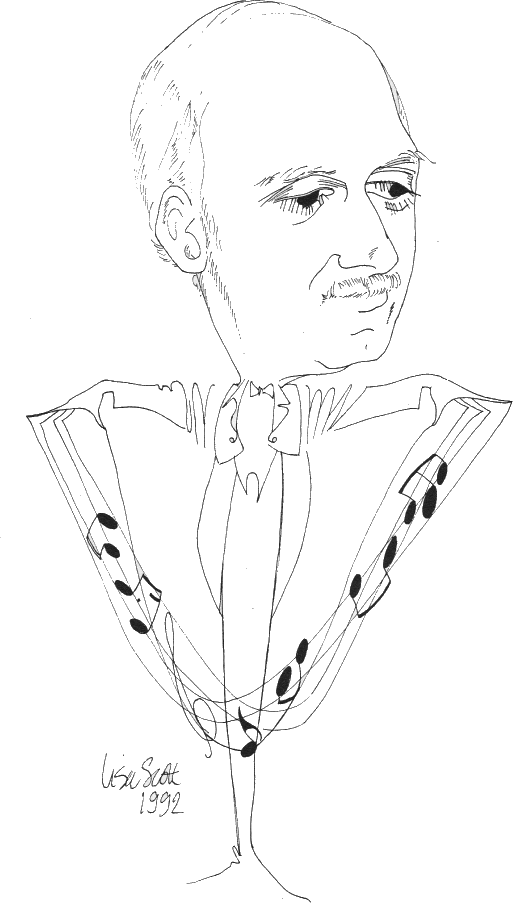

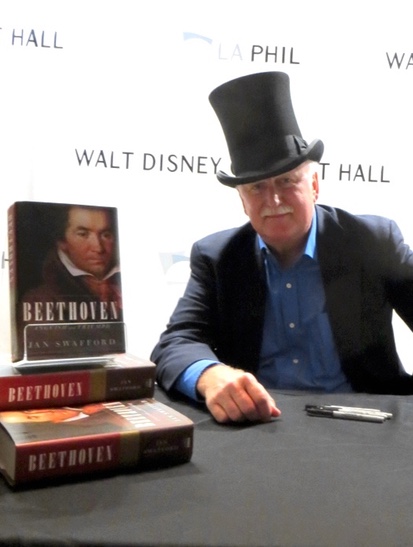

Jan Swafford’s new biography of Beethoven, a personal and loving contribution to the literature, even has a Lifetimeish subtitle: “Anguish and Triumph.” The triumph, of course, is the triumph of will through artistic creation; the anguish is copious failures of the body: “deafness, colitis, rheumatism, rheumatic fever, typhus, skin disorders, abscesses, a variety of infections, ophthalmia, inflammatory degeneration of the arteries, jaundice and at the end chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis of the liver.” When Beethoven’s body wasn’t betraying him, he was destroying himself, sabotaging his most important relationships, succumbing to destructive obsessions. Between these willful and fateful destructions, he squeezed out the miracle of his music. (Lazy readers, I just saved you 1,077 pages; you’re welcome.)

Swafford’s voice is genial and conversational, that of a friend who loves to tell you about his fascinations: the foibles of court life, logistical problems of the musician. He supplies a generous chapter on the German Enlightenment, connecting threads of the 1770s and ’80s, opposing currents of rationalism and expressive release: Schiller, Kant, Goethe, the American Revolution. He nods toward Beethoven’s unhappy childhood, but emphasizes “the golden age of old Bonn’s intellectual and artistic life” and “the town’s endless talk of philosophy, science, music, politics, literature.”

The narrative acquires momentum when Beethoven reaches his darkest hour (Heiligenstadt, 1802). In one of the best chapters, Swafford considers the tune of the last movement of the Third Symphony, an englische , a dance connected to democratic ideals (according to Schiller, it was “the most perfectly appropriate symbol of the assertion of one’s own freedom and regard for the freedom of others”), then heads off to the wider European stage to watch a dubious moment in democracy: Napoleon being proclaimed first consul for life. Swafford’s craftsmanship shines in the meeting of these contrapuntal lines: Beethoven’s personal heroism against illness and adversity, Napoleon’s world-conquering heroism, both seemingly servants of broader freedoms.

This book is two books: a biography and a series of journeys through the music, a travelogue with an excitable professor. Readers will want to have a recording playing, so they can match metaphors to sounds. I found myself engaged by his imagery, sometimes delighted and surprised, often bewildered, and occasionally furious. The descriptions include the clinical, but trend Romantic: A climax of the “Waldstein” Sonata is like “a gust of wind that shocks the listener into a sense of the joyous effervescence of life.” There is silliness: The last movement of a sonata “begins with a couple of can’t-get-started stutters followed by sort of a sneeze.” When Swafford described the middle movement of the “Appassionata” as “somber,” I threw the book on the floor, Beethoven-style. The piece is the opposite of gloomy; its gesture, its reason for being, is to reach up in a gradual arc toward elation.

Swafford repeatedly points out the way Beethoven cunningly derived pieces from a single, simple idea. This is not news — but it’s worth meditating on. Beethoven preferred musical ideas of almost unusable simplicity, things that seem pre-musical, or ur-musical, like chords, or scales — not music, but the stuff music is made of. Imagine a building constructed of blueprints, or a novel based on the word “the.” To demonstrate this, Swafford focuses on a magical aha moment: Beethoven has just figured out how he’ll begin the Fifth Symphony, with a motif we know all too well. “Then something struck him,” Swafford says. “He jotted down an idea in G major . . . the melodic line, virtually intact, of the opening piano soliloquy of the Fourth Piano Concerto.” This other melody is built on the same rhythmic DNA, the same da-da-da-dum, but in place of agitation, you have the most gorgeous benediction, a melody of unbelievable tenderness. There they are, on facing pages: two of the greatest musical works of all time, born from the same piece of Morse code, a single unit of rhythm that was turned in Beethoven’s mind (at the moment of creation!) to utterly opposing ends.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Discount Dozen

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

| Our Shelves |

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

| Gift Cards |

Beethoven: Anguish and TriumphJan Swafford’s biographies of Charles Ives and Johannes Brahms have established him as a revered music historian, capable of bringing his subjects vibrantly to life. His magnificent new biography of Ludwig van Beethoven peels away layers of legend to get to the living, breathing human being who composed some of the world’s most iconic music. Swafford mines sources never before used in English-language biographies to reanimate the revolutionary ferment of Enlightenment-era Bonn, where Beethoven grew up and imbibed the ideas that would shape all of his future work. Swafford then tracks his subject to Vienna, capital of European music, where Beethoven built his career in the face of critical incomprehension, crippling ill health, romantic rejection, and “fate’s hammer,” his ever-encroaching deafness. Throughout, Swafford offers insightful readings of Beethoven’s key works. More than a decade in the making, this will be the standard Beethoven biography for years to come. There are no customer reviews for this item yet. Classic Totes Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more! Shipping & Pickup We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail! Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club! Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.  Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore © 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected] View our current hours » Join our bookselling team » We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily. Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual. Map Find Harvard Book Store » Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy » Harvard University harvard.edu »

‘Beethoven’ by Jan Swafford Given the anvil-like solidity of this new Beethoven biography from Slate regular Jan Swafford, it’s clear that an attempt is being made to cleave a sizable space among the various works centered on the life of the man who is perhaps the most famous of all composers. Swafford has a knack for bringing in the reader wholly unschooled in the technical vernacular of classical music. That skill is in evidence in this blend of biography and musical assessment. Even if you don’t know the difference between a leitmotif and a lighthouse, don’t sweat it, for this is, more than anything, a saga of a man at odds with so many things: convention, social mores, himself, women, his family, scullery maids. You name it, and Beethoven was pretty much battling against it, all the while with a good deal of self-awareness about it. Advertisement Swafford meticulously traces Beethoven’s life (1770-1827) and music from his childhood in Bonn, the early signs of his talent (and his father’s attempts to exploit it for cash), the flowering of his skills in his 20s, deafness at 27, and his already well-known accomplishments beyond. Throughout, the portrait we get is of an artist who was an utter failure at relationships — seemingly undermining himself and any prospects of personal happiness — but a soaring, driven genius. Violent tempered, lacking in social skills, gruff to the point of being domineering, Beethoven didn’t exactly exude warmth. Which is ironic, given that we also have one of history’s great humanists, albeit one housed in the persona of a curmudgeon. Beethoven clearly believed certain things were just owed to him, and his attitude is one of a king believing himself possessed of divine right. This is hardly a way to go about one’s relationships, as Swafford lays plain, but, paradoxically, that level of self-immersion lends itself to heroic writing stretches. We learn that he was obsessed with Countess Josephine (and Beethoven was a veritable league leader when it came to racking up incidents of unrequited love), and his rage became such that “Josephine had ordered her servants not to let him in the house.” Swafford is a careful writer and knows exactly what the implications of this language are, the notion of Beethoven as some kind of protean beast in occasional need of being pent up, a man whose affections could be described as “a fury of his love.” If this isn’t exactly the Beethoven that Schroeder of “Peanuts” fame worshiped, it’s a more believable characterization, and, more than that, one gets a better sense of how this roiling personality produced works to roil the human soil. The depth of feeling in his compositions indicates a mind of all-out intensity, be that for raw, dramatic musical power, or phrases so alluringly beautiful that you’d think they must have been authored by the most sweet-tempered of men. The longtime reader of Beethoven biographies is apt to find that of Maynard Solomon heavier on musical analysis, but if you’re not well-versed in musical shop talk, you’ll be lost. Alexander Wheelock Thayer’s multivolume “The Life of Ludwig van Beethoven’’ remains your best bet, but that Beethoven rollicks a bit too much to be a totally accurate Beethoven. My own personal hope was that Swafford’s effort might be as spry as some of his Slate columns on classical music, but it’s more serious. It is, however, impressively researched, including recorded remembrances of friends and family, portions of his letters, and examples from his scores. Even in Beethoven’s early days, with his father playing up the prodigy angle — being a prodigy was big business in the 18th century — by lying about his son’s age, the boy handles himself with such assurance that he seems like a 50-year-old man. Swafford duly quotes letters that has Beethoven sniffing at how outmoded a given country was, and how he’d never be back, never mind that he hadn’t even hit his teen years. The steady beat of purpose flowed through the young genius, even before he was capable of producing genius. And yet, for all the grousing, all the mean-spiritedness of which he was capable, Beethoven had a preternatural calm within himself, a paradoxical stillness amid his rages — notes of thunder, formulated in quiet, otherwise ordinary moments. Which perhaps renders this biography of Beethoven an indirect examination of the workings of genius itself. Colin Fleming is the author of the forthcoming “The Anglerfish Comedy Troupe: Stories From the Abyss.”  Jan Swafford's Essential Beethoven Biography“What Beethoven wanted from pianos, as he wanted from everything, was more: more robust build, more fullness of sound, a bigger range of volume, a wider range of notes. As soon as new notes were added to either end of the keyboard, he used them, making them necessary to anyone wanting to play his work. From early on, piano makers asked for Beethoven’s opinion, and they listened to what he said.” —Jan Swafford  Beethoven crowns classical music as the most prodigious of all the classical composers, immortalized for unleashing, as in the case of his Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55 otherwise known as Sinfonia Eroica , his unbridled vehemence upon the keyboard in an electrifying battery of acoustical assault, consequently breaking hammers and piano strings at times. And yet, within the very same breath, he could also cast his hypnotic spell upon rapt listeners, delicately tracing out sustained legatos for works like the “Moonlight Sonata” that provide us a glimpse into the psyche of a man (as opposed to the monster), trapped by the weight of his creative genius and titanic persona, tormented by the emotional suffering of his mortal yearnings. Beethoven was tremendously frustrated by the inability of the fortepianos of his day , with their wooden frames and limited span of five octaves—versus today’s seven—to emote the dynamics and nuance that his compositions required. Modern pianos are constructed of steel frames, which, along with other improvements, are much stronger and can deliver a more robust sound. It wasn’t until 1817 that British piano maker, Broadway, finally produced a grand piano with dynamic range designed to Beethoven’s satisfaction, only by then, he had already lost most of his hearing. Nevertheless, Beethoven set himself to composing and improvising for his new beast. “Once he began to revel in the infinite world of tones, he was transported also above all earthly things—his spirit had burst all restrictive bonds… Now his playing tore along like a wildly foaming cataract…and anon, he sank down, exhausted, exhaling gentle plaints, dissolving in melancholy. Again, the spirit would soar aloft, triumphing over terrestrial sufferings.” Beethoven was at the peak of his career when he began to suffer the effects of hearing loss, a few years prior to composing the Sinfonia Eroica . Listen and you’ll hear the development of the four movements as a reflection of his inner turmoil: confusion, despair, and trepidation as he grew increasingly isolated and depraved by his condition. In 1802, he penned the Heiligenstadt Testament , a suicide note written to his brothers that was published following his death in 1827.  “For us, what better way to imagine the late music, its sense of an interior singing, its uncanniness that seems to transcend the actual instruments. That spirit, too, ultimately rose from the hard hammers and cold metal strings of the mechanism that Beethoven had done so much to shape…” Composer and author Jan Swafford’s B eethoven: Anguish and Triumph , is an intriguing must-read for any Beethoven or classical enthusiast. His definitive tome on the greatest composer to have ever lived mines historical documentation—personal letters, press clippings, reviews, memoirs, etc.—to portray both the anguish and the triumph of this singular musical giant.  Hey! Did you enjoy this piece? We can’t do it without you. We are member-supported, so your donation is critical to KCRW's music programming, news reporting, and cultural coverage. Help support the DJs, journalists, and staff of the station you love. Here's how:

It’s our Fall Pledge Drive and we have a $20,000 challenge from KCRW Champions Lauren and Austin Fite on the line. Donate before midnight! double dollars

Beethoven 250Beethoven's 'eroica,' a bizarre revelation of personality.  Buy Featured BookYour purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

Deceptive CadenceBeethoven's famous 4 notes: truly revolutionary music, helen keller's glimpse of beethoven's 'heavenly vibration'.  ORCHESTRA & WIND ENSEMBLEFROM THE SHADOW OF THE MOUNTAIN (2001), for string orchestra. Commissioned and premiered by the Chamber Orchestra of Tennessee, Chattanooga, September 2001. EXCERPT ADIRONDACK INTERLUDE (2001), for orchestra. Commissioned and premiered by the Skidmore College Orchestra, April 2002. LATE AUGUST: Prelude for Chamber Orchestra on Southern Themes (1992). Full orchestra version, 1998. Premiered by the Minneapolis Chamber Symphony, March 1992. Published by Peer. CHAMBER SINFONIETTA (1988), for chamber orchestra. Written for and premiered by Boston's Alea III, March 1988. Published by Peer. Won Massachusetts Artists Council Grant 1989. AFTER SPRING RAIN (1982), for orchestra. Commissioned and premiered by the Chattanooga Symphony 1982. Published by Peer. Won Indiana State University Composition Contest 1983. EXCERPT LANDSCAPE WITH TRAVELER (1980), for orchestra. Premiered in a public reading by the American Composers Orchestra 1988. Published by Peer. POINT: GENESIS: MATRIX: MUSIC FROM THE MOUNTAIN (1969-72), for wind ensemble. First movement premiered by the Boston Conservatory Wind Ensemble 2012. PASSAGE (1975), for strings, piccolo, and percussion. Premiered by the St. Louis Symphony 1976. Chosen for International Gaudeamus Festival 1977. CHAMBER MUSICTHEY THAT MOURN (2002), for piano trio. In memoriam 9/11. Commissioned by Market Square Concerts for their 25th Anniversary celebration. Premiered by the Peabody Trio in Harrisburg, PA, April 2002. Published by Peer. Recorded on CRI. EXCERPT REQUIEM IN WINTER (1991), for string trio or string sextet. Written on an NEA Grant. Premiered by the Scott Chamber Players, Indianapolis, Nov. 1992. Published by Peer. CAPRICES (1989), for piano and three winds. Commissioned by the Sylmar Chamber Ensemble of Minneapolis. Premiered in Minneapolis, Feb. 1989. THEY WHO HUNGER (1989), for piano quartet. A Chamber Music America commission for the Scott Chamber Players. Premiered by the Scott Chamber Players in Indianapolis 1989. Published by Peer. Recorded on CRI. MIDSUMMER VARIATIONS (1985; second version 1987), for piano quintet. Commissioned and premiered by the Minnesota Artists Ensemble 1985. Published by Peer. Won Massachusetts Artists Council Grant 1989. EXCERPT LABYRINTHS (1981), for violin and cello. Premiered at Yale 1982. Won New England Composers Competition 1984. OUT OF THE SILENCE (1979), for winds and strings. Premiered in New York by Musical Elements 1979. FLEURS (1978), for five flutists. Commissioned and premiered by the St.Louis Flute Club 1979. PEAL (1976), for six trumpets. Premiered at Yale 1977. Chosen for the International Gaudeamus Festival (Holland) 1978. EXCERPT THE GARDEN OF FORKING PATHS #3 (1974), for five winds. Premiered at Yale 1974. THE GARDEN OF FORKING PATHS #2 (1971), for flute and piccolo trumpet. Premiered at New England Conservatory 1971. Published by Meridian. STRING QUARTET (1968). Premiered at Yale 1976. KEYBOARD AND SOLO INSTRUMENTIN TIME OF WAR (2007), for cello and piano. Written for and premiered by Emanuel Feldman and George Lopez, New England Conservatory, May 2007. EXCERPT IN TIME OF FEAR (1984), for flute and harpsichord. Premiered in Deerfield 1984. SOLO INSTRUMENTTHE SILENCE AT YUMA POINT (2011), for solo cello. Written for and premiered by Rhonda Rider, February 2011. A CELEBRATION WITH CATHY (2007), for solo viola. Premiered by Ronald Gorevic, Smith College, November 2007. MUSIC LIKE STEEL AND LIKE FIRE (1983), for solo piano. Premiered Smith College 1985. Won Delius Competition'89. THEATER AND VOCAL MUSICIPHIGENIA (1993), for women's choir and ten instruments. (Concert version with narrator.) Original theater version commissioned by the University of Tennessee. Premiered in Chattanooga, Nov. 1993. SHORE LINES (1982), for soprano and flute. Premiered in Deerfield 1983. Published by Meridian. Performed at National Flute Conventions 94 95. Won a National Flute Association Award for newly published work, 1995. EXCERPT THE GOOD WOMAN OF SETZUAN (1977), for voices and chamber ensemble. Premiered at the Yale School of Drama 1977. MIXED MEDIAMAGUS (1977), for cello and tape. Premiered by Gerhard Pawlica at Boston University 1978. EXCERPT  MUSIC REVIEWSSwafford's piece is a private outpouring scaled to a deeply felt, intimately scored trio that opens with a piano rippling high above a sighing cello lamentation. Sweeping in its momentum, direct in its expression, the work passes through the full gamut of moods and includes an exuberant dance section that seems to channel the energy of the trios of Ravel or Shostakovich before a mournful tone is reestablished at the close. "I wanted an elegy to reflect the tumult of feeling with which mourning runs its long course," he wrote in an explanatory note, "a course in the direction, sometimes, of reclaiming hope and joy." —Jeremy Eichler in The Boston Globe , April 2011 While After Spring Rain builds up some of its continuity with repeated orchestral chords in a rather John Adams-ish way…nothing could be further from Adams than the wandering flute duet with which After Spring Rain opens…Swafford owes nothing to Adams, nor to minimalism. Nor, apparently, to twelve-tone music…The music gives no sense of having backpedaled from modernism out of populist guilt, nor is there any vestige of pitch-set thinking, nor any hint of serialist fragmentation. His music unremittingly lyrical and linear…He has not been drawn into the aesthetic squabbles of twentiety-century music. His style…is entirely his own. —Kyle Gann in a feature article for Chamber Music , May 2005 The concert really got down to business with Jan Swafford's highly evocative After Spring Rain played by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra at the Contemporary Music Festival. The exquisitely scored work is rich in mood and atmosphere, spare and transparent in sound and lyrical in effect. —Charles Staff in The Indianapolis News , March 1993 The aftermath of Jan Swafford's After Spring Rain was a respectful appreciation and even a little awe. It's a gorgeous work, rich in textures and colors and emotional tension….True to his own words, his music "sounds only like itself." —Lucy Miller in The Pennsylvania Beacon , March 1984 Put together skillfully and full of sophisticated demands on the musicians, They Who Hunger nonetheless gets down to street level in its range of expression. Through the score's use of grating dissonance to convey anger and turmoil is restrained, it leaves and breathes the energy and pathos of common lives…In its main thematic material and the frequency of lively rhythmic patterns recalling country fiddling and banjo music, the music stays in touch with demotic roots from first to last. It shuns both imitation folk music and more literal borrowings from popular kinds of music…The 20-minute work seems a model of economy without getting stingy about it…Instead it is richly detailed, marked with almost secretive flourishes. —Jay Harvey in The Indianapolis Star , October 1989 The provocation for Jan Swafford's piano quartet They Who Hunger was the plight of the homeless…Though the subject matter is not discernible in any overt way, the piece has a world-weariness that is no doubt expressive of the composer's feeling. Otherwise, the music is jaunty with motoric rhythms, lyrical and bluesy. —Anthony Tommasini in The Boston Globe , November 1990 While compassion may have motivated him, Swafford in They Who Hunger has composed a purely musical work…There is no text, no program…The work opens with an eloquent, poignant violin theme that is quickly taken up and varied…There are many more ideas that take place with considerable speed and fluency. Among the most attractive features are Swafford's ability to create unusual and haunting sonic combinations and colors, such as the section in which there are bowed tremolos in the cello against a violin and viola melody and fragments of filigree in the piano. —Ellen Pfeifer in The Boston Herald , November 1990 While any of the three winners on this League of Composers/ISCM program could well have been written 15 years ago, they wouldn't necessarily have won…"In order to say what I wanted to say," the composer writes, in Labyrinths "I had to reinstate a number of things that had largely vanished from new music by the last decade—an ebb and flow of harmonic tension, pulsed rhythms, lucid counterpoint, lyric melody and the like." The result, in this piece, is a fresh, canny, terse use of accessible materials, nothing bogus or fogeyish about it. —Richard Buell in The Boston Globe , March 1985 Let me report that Jan Swafford's Midsummer Variations stands a good chance of long-term survival…I like it because at all points it struck me as solidly built, like a piece of furniture. The fast section is particularly vivacious, and the ending both spacious and handsome. —Roy M. Close in the St. Paul Pioneer Press Dispatch , November 1985 Swafford's 1985 Midsummer Variations …frolics in a meadow of a century's breadth. One detects..touches of dissonance, jovially vulgar syncopation, stylized hoedown romps, but most of all, a richly Romantic conception at home in an atomized time…The 1989 They Who Hunger stands in introspective contrast as a politicized utterance…Swafford aptly quotes Joseph Brodsky: "The artist's main responsibility to society is to write well." And Swafford does write well—very well indeed…The work's harmonies are at once lush and elegiac, and despite the music's sober purpose, patches of something like gaiety spice…The music surges with a kind of luminous viscosity I find both attractive and touching —Mike Silverton in Fanfare , February 1994 As this new CRI release shows, Swafford writes superbly in the new romantic manner. His Midsummer Variations begins with a dark angry gurgle and then a piercing screech in the strings. The listener wonders: Is this going to be a 60's-style noisy, athematic, "sonoristic" exploration of colors and effects? No, it isn't. Not two minutes have passed before Swafford shows…an opulent, faintly-exotic melody…Later variations take the tune through a minimalist barn dance…and eventually to its apotheosis in a slow, meditative chorale…In They Who Hunger Swafford's inspiration is the tragedy of "the many too many." Its emotional world is more wide-ranging and intense, including both exuberance and anger as well as elegiac resignation; occasional echoes of "the blues" fit smoothly into Swafford's idiom…The most immediate appear of this excellently performed and recorded disc is in Jan Swafford's beautiful answer to what comes after Modernism. —Lehman in American Record Guide , November 1993  JAN ON YOUTUBEA search there for Jan Swafford will turn up extensive commentary on the Beethoven quartets and symphonies, plus a chat with Hilary Hahn about Charles Ives and a discussion about Beethoven with Dr. Gail Saltz, which was done at the NY 92nd St. Y last year. There is also an outstanding complete performance of the piano trio, They That Mourn . Watch Videos PUBLICATIONS

PUBLICATION REVIEWSFor Charles Ives: A Life with Music — In Swafford, Ives got the biographer he deserves, Thoughtful, witty, instructive, this is one of the best biographies in recent memory, as warm and strangely inspiring as the man and the music it describes. —Malcom Jones Jr. in Newsweek , September, 1996 For Johannes Brahms: A Biography — The definitive work on Brahms, one of the monumental biographies in the entire musical library. — The Weekly Standard For The Vintage Guide to Classical Music — I can think of no more entertaining of well-priced instrument of propaganda for the Serious to lay on a recalcitrant near-&-dear with intent to develop...a glimmer of interest in that which consumes you and me….I'll be thumbing through this for edification and kicks long after I've handed in my review. Though Mr. Swafford is no debunker, he stops well short of the Ives idolatry and ideological camp following that weaken older studies…And yet there is never a doubt about which side of the Ivesian divide he stands on. He is one of those informed enthusiasts whose fervor can be contagious. —Donal Henahan in The New York Times , August, 1996 A meticulous portrait…Swafford has thoroughly mined the existing literature, both scholarly and popular, and has managed to weave it into his narrative in a seamless fashion…At times the writing unfolds with remarkable lyricism and sweep. — Los Angeles Times In many ways, the book does resemble a work of Ives. It is sprawling, rich with fascinating details, quirky, opinionated, and very appealing. The opening paragraph consists of one 203-word sentence that paints a colorful, Romantic portrait of the Ives homestead…in a manner that will remind readers of Ives's own tonal landscapes. —Larry A. Lipkis in Library Journal , August, 1996 Jan Swafford's intelligent, gracefully written biography…offers perhaps the richest and most integrated portrait we've yet had of Brahms as man and artist. — The Hartford Courant Jan Swafford's Charles Ives goes a long way toward dispelling or clarifying many of the most prominent myths surrounding the life and music of perhaps American's greatest composer….Swafford's biography presents us with the most complete picture yet of this fascinating and often contradictory man and his music. —Kenneth Singleton in The Washington Post , July, 1996 Swafford's analysis of Brahms's performing career as pianist and conductor is especially fascinating. — The New York Times A sensitive, specific, gracefully worded, and remarkably clearheaded book that is both an engrossing biography of a craggy, idiosyncratic New England "character" and a detailed examination of the work he left behind. — Washington Post Book World , Editor's Choice The author of the much-acclaimed biography Charles Ives: A Life with Music , Swafford has produced yet another masterpiece. This voluminous work combines formidable scholarship with an engaging, can't-put-it-down writing style. — Library Journal An extraordinary story, and Mr. Swafford tells it brilliantly…A rich portrait of a great, lovable man…This is much more than a narrowly musical biography: it should be on the shelves of anyone interested in the history of the past century. — The Economist Review Swafford's is a thoughtful and sympathetic telling of Ives's life…thoroughly researched and fun to read…what makes this book so valuable is Swafford's skill in weaving the strands of all these areas of knowledge into a cohesive fabric. It is as close as we may come for quite some time to a complete Ives. —Josiah Fisk in The Hudson Review Swafford has written a scrupulously detailed and unfailingly enthusiastic biography of the great Connecticut composer, whom he sees not only as the natural product of turn-of-the-century Progressivism but as a musician "invaded by the future." — The New Yorker OTHER ESSAYS—

ARTICLES ONLINE AND IN PRINT

Selected speaking engagements-- Boston Symphony Orchestra (preconcert talks 2003--); Carnegie Hall (Ives); Rosendal Norway Chamber Music Festival 2017 (Mozart) & 2019 (Beethoven); Detroit Symphony (Brahms); WIGMORE HALL, London, 2020 (Beethoven Piano Sonatas); BBC RADIO 3, 2020 (Beethoven); Manhattan String Quartet symposium in Krakow, Poland (Beethoven) and in Bonn, Germany (Beethoven); GRAND TETON AND SUN VALLEY MUSIC FESTIVALS 2019 (Beethoven); Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (Elgar); Oslo Ultima Festival (Beethoven); Los Angeles Philharmonic (Beethoven); BEETHOVEN CENTER SYMPOSIUM, San Jose. 2020 (Beethoven's Chamber Music); Rockport Chamber Music Festival (Beethoven); Schenectady Chamber Music Series (Schubert); Barcelona Conservatory (Beethoven); Ottawa National Arts Center Beethoven Festival (Beethoven); University of Kentucky (Beethoven); talks with Dr. Gail Saltz at the 92d St. Y (Brahms and Beethoven); Camerata Pacifica of Santa Barbara (Beethoven); Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (Beethoven); Skidmore College (Ives); Texas Christian University (Ives); University of Arizona School of Music (Ives). Interviews in the films Wagner’s Jews; Beethoven's Joseph Cantata; a German documentary on Charles Ives, in progress; two Beethoven films in progress on Fidelio and the late quartets. SELECTED MUSICAL HONORSWRITING HONORS

Peermusic Classical 250 W. 57th St., Suite 820 New York, NY 10107 Tel: (212) 265-3910 ext. 17 Fax: (212) 489-2465 E-mail: [email protected] Email Jan's email is [email protected] Meridian Publishing (913) 956-7270 E-mail: [email protected] Jan Swafford began writing music as a teenager in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He was then a trombone player aspiring to become a high school band director, which as he then understood it was the pinnacle of a musical career. By the time he left for Harvard in 1964, he was determined instead to be a composer, an endeavor he had little knowledge of beyond the desire to pursue it. At his high school graduation he conducted his wind ensemble piece The Class of '64 , a work recalling bits of Pomp and Circumstance, Walton's Crown Imperial, and random other band pieces. It was declared "promising." At that point Swafford had more desire than application; during college he added relatively little to his portfolio while he coped with a musicology-oriented program. Otherwise he played trombone in the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra and, as a senior, studied composition in the seminar of Earl Kim. By the end of college he had completed two movements of a string quartet, which he finished the next year. The quartet, which by his later standards he considered occasionally interesting, was premiered some years later, after which it was not allowed out of the house. Swafford graduated magna cum laude , based on his thesis on Charles Ives's Fourth Symphony. By the end of college in 1968, he knew more about Renaissance motets and Wagnerian music drama than he did about being a composer. An aside: In 1969, as part of a serendipitous crosscountry trip, Jan Swafford and Jan Gippo (later piccolo with the St. Louis Symphony and Swafford publisher) stood on a cliff in the middle of Grand Canyon at sunset, arguing about whether the scene in front of them was best expressed by Ives's Fourth (Swafford) or Brahms's Fourth (Gippo). The idea that Swafford would eventually write biographies of both those composers would have been incomprehensible to them both. The Canyon trek was the beginning of a lifetime of hiking for reasons more inspirational than athletic. The year of Swafford's college graduation was the time of the Vietnam War. Afflicted with a low draft number and not gifted as a killer, he took the available opportunity and became a public school music teacher in Marblehead and Vermont. While he directed choirs and musicals and taught "music appreciation" to sullen teens, he began to compose intensely for the first time, a series of pieces he hoped would get him into graduate school. The compositional plan more or less succeeded, though few of Swafford's works had been performed by the time he could return to school. He was accepted by every graduate institution he applied to--except Harvard. In any case his choice was the Yale School of Music, where he began in 1974. Of the works of his previous schoolteaching years still allowed out of the house, the most ambitious was a piece for wind ensemble called Point: Matrix: Genesis: Music from the Mountain , whose ca. 40 minutes perhaps justifies its exhausting title. The first movement, finished in 1971 and dubbed MountainMusic , was finally premiered in 2010 by the Boston Conservatory Wind Ensemble. A smaller work was The Garden of Forking Paths #2 for flute and piccolo trumpet, now published by Meridian Music. In programs at Yale Swafford was finally able to hear most of his older pieces, which sounded to him like a dream magically played out in reality. He studied composition with David Mott and Jacob Druckman, meanwhile taking courses in electronic music and contemporary pitch relations with Robert Morris, and classes in choral and instrumental conducting and score analysis. Works of those years include Passage for piccolo, strings, and percussion (premiered by the St. Louis Symphony with Jan Gippo soloing) and Peal for six trumpets. Both those works were heard at the Gaudeamus Festival in Holland. His Magus for cello and tape helped win Swafford notice as a Rome Prize Alternate. (It has been revived in the '00s in outstanding performances by cellist Emmanuel Feldman.) After graduate school he was a Tanglewood Fellow, where he studied with Betsy Jolas and completed the solo part of Magus (it has been rewritten twice since). He received a Yale DMA in Composition in 1982. In the next years Swafford completed a variety of pieces while being a gypsy college professor and semi-happily unemployed. In one of the latter periods he stumbled into writing prose to pay the rent: He produced several for-hire history books, most of them having to do with wars and other mayhem, for a dime a word. These books were sold in K-Mart next to gaily-illustrated volumes such as Armaments of the Third Reich and Cats! Cats! Cats! In those jobs he learned to research and write history, though at the time he had no plans to make further use of those skills. Meanwhile he became a music critic for the late magazine New England Monthly . During those years more or less in the wilderness, Swafford wrote Labyrinths for violin and cello, Shore Lines for soprano and flute, and the orchestral After Spring Rain on a commission from his hometown Chattanooga Symphony. By then much of his work was inspired by and evocative of nature. At the MacDowell Colony he completed his most ambitious orchestral piece, Landscape with Traveler , conceived while contemplating the Green Mountains from the top of Mt. Mansfield in Vermont, and created with reference to Chinese landscape painting. Then and later, Swafford has pursued an individual conception of classicism, which to him is a matter not of style but of directness and lucidity of gesture and form on one hand, on the other hand a search for a "natural" voice: something that seems right and familiar even though it is new. He believes that in the contemporary world of music, in which there is no common language, a work should, as it goes, explain its language for the ears of the listener. Some of his music is tonal, some not; some is atonal but sounds tonal. An example of the latter is the beginning of Passage , which for two minutes constantly involves all twelve notes but sounds like tonal chord changes. One critic described some of his works as triadic when in fact there is no triad in any of them. Swafford takes ironic pride in that error. In his work there are no dogmas and no ideologies, instead a concern with clarity, expressiveness, and the ways that music can relate to the stuff of life. He is constitutionally wary of theories, including the ones he makes use of. Whether his works sound on the surface "modern" or "conservative," the imagination and the goals are the same. What is important to him are the ideas at hand, where they seem to want to go. Which is to say that all his endeavors Swafford regards himself as a chameleon in the best sense: He places himself in a context and his creative response adjusts its colors to fit it. In all cases, as best he can tell, he sounds only like himself. For more information on works, prizes, and publishers, see the relevant sections on this website. Some of his works are published by PeerMusic. Some are available on Spotify and ITunes, and a https://www.aol.com/splendid complete performance of They That Mourn is on YouTube. Works of the last decades include his theater music for Iphigenia , premiered at gala performances in Chattanooga; the Chamber Music America commission They Who Hunger for piano quartet; Requiem in Winte r for string trio, written on an NEA Fellowship (there is also a sextet version); From the Shadow of the Mountain , a commission from the Chamber Orchestra of Tennessee; and They That Mourn , commissioned for the 25th Anniversary of the Harrisburg Chamber Music Festival, where Swafford was Composer in Residence. The Silence at Yuma Point for solo cello, written in 2012, has been recorded and widely performed by Rhonda Rider, for whom it was written. Also a writer and journalist, Swafford has completed three major biographies of composers: Charles Ives: A Life with Music , Johannes Brahms , and Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph . Ives was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle prize and won the Pen-Winship award for New England book of the year. Ives and Brahms were Notable Books for their years in The New York Times. Swafford's Vintage Guide to Classical Music has long been a standard introductory book. His recent introduction to music Language of the Spirit was an Arts best seller on Amazon. His biography Wolfgang Amadé Mozart: The Reign of Love will be out in 2020. Swafford's journalism has appeared in Slate; for it he was awarded a Deems Taylor Prize for online writing. O therwise he has written for a bewildering collection of publications including The Guardian , 19th-Century Music , Wilson Quarterly , Gramophone , Opera, and Yankee. He is a longtime writer of program notes and preconcert lecturer for the Boston Symphony, and has written notes for the orchestras of Cleveland, San Francisco, Chicago, and Toronto. On radio he has been heard commenting on this and that for NPR, CBC, and BBC. In 1988 Swafford was named a Mellon Fellow at Harvard, where he worked on the Ives biography and taught a seminar in American music. That led to a return to teaching. At Boston Conservatory he taught Composition, Theory, and Music History. As of this date Swafford is finishing the Mozart biography, composing songs, and contemplating a major wind ensemble piece that will return to something like the world of MountainMusic, but in which he hopes to have a better idea of what he is doing. Its subject is the Grand Canyon. Boston Symphony Program Note: Beethoven's Seventh SymphonyEvery scholar wants to be a revisionist and Beethoven scholars are no exception, though their success has been constrained by an old paradigm of Beethoven scholarship, the division of his work into three periods: the Early, when he was learning his craft and finding his voice; the Middle, aka Heroic, a flood of bold and legendary masterpieces; the sublime Late, when he was isolated by illness and deafness and his music became inward and spiritual. If the doctrine of the three periods has survived all assaults so far, it has acquired a thicket of hedges, caveats, and sub-periods. For example, when it came to his own instrument the piano, the Middle arrived early: some of the early piano sonatas and trios, notably the Pathétique , are more confident and individualistic than, say, the first two symphonies and first half-dozen string quartets. And the music of the Heroic period, in the eight years or so after the Eroica Symphony in 1802, is by no means all heroic in tone. The abiding relevance of the three periods gives particular interest to prophetic works like the Pathétique , and to works lying on the boundary between two periods. In the latter position we find the two most surprising of Beethoven's mature symphonies, the roaring, unbridled Seventh and the witty, backward-looking Eighth. One speaks of them together because they were written together, both finished in 1812. Another hoary tradition of Beethoven studies is that he tended to work on more than one piece at a time, and those pieces, notably the pairs of symphonies, are remarkably contrasting in material and tone, a prime example being the Seventh and Eighth. By 1812 much had changed in Beethoven's life and career since the extraordinary period between 1802 and 1809, when he produced a flood of masterpieces perhaps unprecedented in the history of music: the symphonies 3 through 6, four revolutionary string quartets, the opera Fidelio , two piano concertos and the Violin Concerto, plus historic sonatas including the Waldstein , Appassionata , and Kreutzer . In 1809, however, around the time of the premiere of the Fifth and Sixth symphonies (on the same concert!) this stupendous level of production abruptly fell off. Though there was much extraordinary music to come, Beethoven never again composed with the kind of fury he possessed in the first decade of the century. What happened? That is conjecture, but some surmises are reasonable. In 1809 Beethoven was given an annual stipend from three noblemen that relieved him, in theory if not always in practice, from financial pressures to produce at the level he had been. Meanwhile his hearing and health continued their long decline. Though Beethoven played piano occasionally in public until 1814 and conducted a few times after, it was obvious that he often could not hear what was sounding around him. By the mid-teens he was wretchedly ill much of the time. However, given Beethoven's ability to transcend physical misery, it is more likely that his decline in production came from expressive quandaries weighing on his mind. He did not scorn money and acclaim and wrote most of his music on commission, but those were not ruling motivations. It seems likely that by 1810 Beethoven had begun to sense that the train of ideas that had sustained him through the previous decade was close to being played out, and he had to find something new. Later he would say as much, but that was after the Seventh and Eighth symphonies. It is in those symphonies, in that genre that he regarded as the crown of his work, and in which he refused to repeat himself, that we see the turn toward the Late period taking shape. In the Seventh Symphony Beethoven put aside for good the heroic model of the Third and Fifth symphonies, the nervousness and intensity of the middle string quartets, but he had not yet arrived at the inward music of the late works--though we see in the Seventh something of the searching harmonic style of his music to come. If not heroic or sublime, then what for the Seventh? A kind of Bacchic trance, dance music from beginning to end. In Wagner's perennial phrase, "the apotheosis of the dance." By all accounts Beethoven was a laughable dancer in person, completely unable to stay on the beat, but on the page he turned out to be a dancer for the ages. This is nothing entirely new in the Classical style Beethoven inherited from Haydn and Mozart. Classical-style music is most often laid out in dance patterns, dance phrasing, dance rhythms. But that hardly explains the Seventh. It dances unlike any symphony before: it dances wildly and relentlessly, dances almost heroically, dances in obsessive rhythms whether fast or slow. Nothing as decorous as a minuet here; it's rather shouting horns and skirling strings (skirling being what bagpipes do). The last movement is based on a Scottish dance tune, but bagpipes don't get that breathless. The symphony's expansive and grandiose introduction strikes a note at once appropriate and misleading: the fast dance that eventually starts out from it seems something of a surprise. But everything significant for the symphony is encapsulated in that introduction: it is the magisterial overture for the frenzied dances to come. From the introduction's slow-striding opening theme many other melodies will flow. But above all the introduction defines the symphony in its harmonies: wandering without being restless so much as brash and audacious, with a tendency to leap nimbly from key to key by nudging the bass up or down a notch. And the introduction defines key relationships striking for the time but ones to be thumbprints of late Beethoven: around the central key of A major he groups F major and C major, keys a third up and a third down. That group of keys will persist through the symphony, just as D and B-flat persist in the Ninth. With a coy transition from the introduction, we're off into the first movement vivace , quietly at first but with rapidly mounting intensity. The movement is a titanic gigue. Its dominant dotted rhythmic figure is as relentless as the Fifth Symphony's famous figure, but here the effect is mesmerizing rather than fateful. Rhythm plays a more central role than melody here, though there is a pretty folk tune in residence. More, though, the music is engaged in quick changes of key in startling directions, everything propelled by the rhythm. From the first time you hear the symphony's outer movements, meanwhile, you never forget the lusty and rollicking horns, which at the time were valveless horns pitched high in A. Nor are you likely to forget the first time you hear the stately and mournful dance of the second movement, in A minor. It has been an abiding hit and an object of near-obsession since its first performances. Here commences, as much as in any single place, the history of Romantic orchestral music. The idea is a process of intensification, adding layer on layer to the inexorably marching chords (with their poignant chromaticism that Germans call moll-Dur , minor-major, later to be a thumbprint of Brahms). Once again, in a slowish movement now, the music is animated by an irresistible rhythmic momentum. For contrast comes a sweet, harmonically stable B section in A major (plus C, a third up). Rondo-like, the opening theme returns twice, lightened, turned into a fugue, the last time serving as coda. The scherzo is racing, eruptive, giddy, its main theme beginning in F major and ending up a third in A, from one flat to three sharps in a flash. We're back to brash shifts of key animated by relentless rhythm. The Trio, in D major (a third down from F), provides maximum contrast, slowing to a kind of majestic dance tableau, as frozen in harmony and gesture as a painting of a ball. The Trio returns twice and jokingly feints at a third time before Beethoven slams the door. The purpose of the finale seems to be, amazingly, to ratchet the energy higher than it has yet been. It succeeds. If earlier we have had exuberance, brilliance, stateliness, those moods of dance, now we have something on the edge of delirium, in the best and most intoxicating way: stamping and whirling two-beat fiddling, with the horns in high spirits again. Does any other symphonic movement sweep you off your feet and take your breath away so nearly literally as this one? The Seventh was premiered in December 1813 as part of the ceremonies around the Congress of Vienna, when the aristocracy of Europe gathered with the intention of turning back the clock to before Napoleon. Beethoven would despise the reactionary results of the Congress, but that was in the future; he was glad to receive its applause. The premiere of the Seventh under his baton was one of the triumphant moments of his life. For the first of many times, the slow movement had to be encored. The orchestra was fiery and inspired, suppressing their giggles at the composer's antics on the podium. In loud sections (the only ones he could hear) Beethoven launched himself into the air, arms windmilling as if he were trying to fly; in quiet passages he all but crept under the music stand. The paper reported from the audience "a general pleasure that rose to ecstasy." True, another piece premiered on the program, Beethoven's trashy and opportunistic Wellington's Victory , got more applause and in the next years more performances. None of that would save him from illness and creative uncertainty, but for the moment he was not too proud to bask a little, pocket the handsome proceeds, even to enjoy with a sardonic laugh the splendid success of the bad piece and the merely bright prospects of the good one. The Seventh after all celebrates the dance, which lives in the ecstatic and heedless moment. Boston Symphony Program Note: Ives Ragtime DancesWe tend to think of composers as always themselves, at least after the juvenilia: Mozart always Mozart, Brahms always Brahms, Ives always Ives. In reality, every significant artist begins with a distinctive temperament but still has to grow into who he or she is. For Charles Ives, that process was bound to be a lengthy one, because he began in a singular place and was headed in a singular direction—a direction he himself only slowly came to understand. The uproarious Ragtime Dances , first sketched c. 1900-04, are an important way station on that journey. A good way to understand the singularity of these dances, and much other Ives, is to recall how he began in music. His bandmaster father George Ives came home one day to find four-year-old Charlie pounding out drum rhythms on the piano with his fists. Rather than saying, as would most parents, "That's not how to play the piano," George said, "That's all right, Charles, But if you're going to play drums, learn to do it right." And he sent his son out for drum lessons. Later there were lots of other lessons; by his teens Ives was one of the finest young church organists in the country. But he never did stop playing piano, now and then, with his fists. Besides training from his father in the conventional ways, Ives got the benefit of George Ives's remarkable musical imagination. George would have his son sing in one key while accompanying in another; he'd march two bands around the Danbury town green playing different tunes, to hear what it sounded like as they passed; he tinkered with quarter-tones. In the 1880s he told Charlie that any combination of notes at all was acceptable, if you knew what you were doing with it. So Charles Ives grew up composing with harmonies and rhythms and conceptions that were unprecedented in the history of music, though prophetic of much to come. The first time somebody told him he couldn't write chords like that was when he got to Yale, in 1894. By then it was too late. Ives submitted, grudgingly, to four years of training in Germanic musical craft, and wrote some distinctive pieces in late-Romantic style. But at fraternity parties and New Haven theaters he indulged his wild side, tone-painting tumultuous events like fraternity initiations and football games, and playing that scintillating new pop style called ragtime. By his rags of the first years of the century, it's astounding how much of the later Modernist musical vocabulary Ives had at his command: polytonality, free dissonance, complex rhythms and shifts of meter, collage-like juxtapositions of ideas that might have been called Cubist, if Cubism had been invented yet—and if the public had heard the pieces, which they didn't. Ives was a private composer by then, and for a long time after. His living came from the insurance business, a job that, unlike his compositions, paid the rent. Still, in those years Ives had not yet reached his maturity. As he was writing the rags and other experimental works, he was also composing large pieces in relatively conventional styles and genres, including the Second Symphony and Violin Sonatas. It was only around 1909, after his marriage, that he began to complete major works in an "advanced" style. The change can be seen by comparing the Country Band March of c. 1905, which is a slight but enjoyable musical joke, and Putnam's Camp of 1914-15, which uses around 75% of the older march but is a fully developed comic masterpiece. The difference is what Ives had learned in the interim as a craftsman and a thinker about music and life. His Ragtime Dances are a young man's portrait of the ragtime years, the decades around the turn of the century, and of the secular life of Manhattan, its bars and its theaters vaudeville and otherwise. No less are these pieces one of several Ivesian testimonials to the skilled and resourceful players of the theater orchestra pit, a venue he knew at first hand. (Ives tried over his ragtimes with several pit orchestras, but found little sympathy.) The four dances are the surviving members of some dozen experiments in ragtime that he produced. These favorites of the lot he apparently orchestrated, but the score is lost; they have been reconstructed from an Ives-annotated piano score. As with many other experimental pieces of that period, when Ives had learned what he needed to know, he put them aside unpolished and moved on. Ives's grouping of the set of Ragtime Dances is rough and ad hoc; he expected performers to pick and choose what to do, and in what order. In this Boston Symphony performance it will be numbers 2, 3, and 4. When he moved on in this case, the dancing syncopations of this African-American style had become a vital part of his musical language. The true, mature Ivesian allegro is a raggy allegro. One hears echoes of these dances in more substantial works for the rest of his career; even the mystical climax of the Fourth Symphony finale has ragtime touches. "Ragtime," Ives wrote, "more than a natural dogma of shifted accents...It may be one of nature's ways of giving art raw material. Time...will weld its virtues into the fabric of our music." By "our" music, Ives meant American. The black invention called ragtime, something indisputably native however African its roots, was to be a key element in freeing Ives of the oppressive weight of the Germanic symphonic tradition that he was nonetheless determined to carry on, but with an American accent. Thus Ives's cubistic Ragtime Dances . Or, as a student of this writer aptly quipped: ragtime run though a blender. The familiar rhythms and harmonies and gestures have been brilliantly skewed, scissored, deconstructed, vandalized and scandalized. All four dances are differing approaches to the same collection of ideas, which for their melodic material are based on old gospel hymns including "Bringing in the Sheaves" and "Happy Day" (the latter a.k.a., appropriately, "How Dry I Am"). Each piece ends with a gospelly peroration on a hymn. The idea is not to sully the sacred with the profane, but the reverse: to bring to this rambunctious secular context a touch of the sacred, a quality Ives found wherever people gathered to make music, in the vaudeville house no less than in the cathedral or at Symphony. A final note: Don't neglect to laugh. There's not enough laughter in concert halls, a shortcoming Charles Ives intended to remedy. His beloved wife considered him a genius, a spiritual force, also the funniest man alive. She said she often had to find a quiet corner of the house to laugh in. Charlie could do it with a word or a glance—or a ragtime dance. Sounds Together and Opposed: Postwar(s) American MusicThe aftershocks of wars and other titanic events reverberate through the generations, and that process affects music as much as any other human endeavor. The term "postwar" is often used as a simple historical marker, but the postwar experience is far more complex than that. A postwar period is a frame of mind, something on the order of culture-wide post-traumatic stress. Also bearing on art are the great movements and ideas of an age: the wave of revolution and reaction across Europe in Beethoven's time; the science of evolution in the American Progressive era (the time of Charles Ives); the influence of Freud and cultural exhaustion and nationalistic reaction in Vienna during Schoenberg's early career. Here I will attempt an admittedly over-large, over-labeled flyover of American music in the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st, its ending point this summer's Aspen Music Festival. The hope is to give some context to the varicolored music that will be on display from the last fifty-something years. What follows a war is a retreat, a sense of relief, often a need to find new rhymes and reasons because the old ones proved disastrous. As of 1945, the Western world had experienced two world wars separated by a depression. The First World War had been followed by the Jazz Age, the decade of "Happy Days are Here Again" before the crash and the bleak 1930s. Before and during WWII, many leading figures in music and the other arts emigrated to the U.S., among them Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Earlier, in the aftershock of the First World War, each of those composers had turned in his own way in a more formal, more rationalized, less freely intuitive direction: Schoenberg to the 12-tone method, Stravinsky to neoclassicism. After WWII, America fell into an overriding concern with calm, peace, predictability. There was a reaction against the leftist eruptions of the Depression years. As the Cold War took shape there were blacklists and purges. The leitmotif of the later 1940s into the 1960s was normality, at all costs. As always, among artists there were many responses to the zeitgeist, some submitting to it, others rejecting it, others planting their heads in the sand. Recall that the conformist 50s were not only the time of chaste Doris Day movies and Father Knows Best ; they were also the time of the Beats and Film Noir. So after WWII the response of music and the other arts to the postwar zeitgeist was inevitably varied and contradictory. As always, some of the leading ideas came from Europe, especially since some of the most influential European artists were now working in the U.S. Partly inspired by their presence, Schoenberg and Stravinsky each had legions of American disciples. After the war Aaron Copland settled into the position of dean of American music. His "Americana" voice from the 30s—owing much to Stravinskian neoclassicism—was no longer cutting-edge, despite his popular postwar essays in the style including the Third Symphony. (Copland allowed his leftist politics of the 30s to be forgotten.) The largely unclassifiable Samuel Barber (with a neoromantic sensibility but affected by the Americana school, in later years experimenting with 12-tone technique) was active from the 1930s through the 1970s. His 1950 Knoxville, Summer of 1915 is a lovely example of how Barber mixed neoromantic and nostalgic American elements into a singular voice. His composing and conducting lives always in competition, Leonard Bernstein was a thoroughgoing eclectic, as seen in the Jeremiah Symphony and Dances from West Side Story in this summer's Aspen concerts. In many ways Bernstein's journeys between popular and classical voices tracked George Gershwin's in the 1920s and 30s—a prime example being Gershwin's An American in Paris . A formidable postwar train of thought flowed from Europe in Schoenberg's 12-tone, eventually dubbed serial , method, in which a whole work is based on a single arrangement of the twelve notes of the chromatic scale. In the work of Schoenberg and his disciples Anton Webern and Alban Berg, the 12-tone method was a theoretical rationalization of their earlier free-atonal music. If the neoclassic faction in some degree resonated with the postwar yearning for peace and normality, the intellectual rigor of serialism rose in part from a drive for rationality after the catastrophic irrationalities of the past decades. In Europe and soon in America, composers including Pierre Boulez took up post-Webern serialism as a holy cause, proclaiming its historical necessity as a new common practice. Meanwhile, Boulez's colleague Karlheinz Stockhausen, who in his youth often saw the remains of his fellow townspeople hanging in trees after Allied bombings, declared that every composer must pursue an endless revolution. In the U.S. the serial idea settled in as an endeavor largely associated with composers in academe. There the dichotomy rested for a while: the often academic atonalists and serialists in one camp, the more popularistic neoclassicists in the other. Then something remarkable happened. After the death of Arnold Schoenberg in 1951, Stravinsky turned from his decades of neoclassic works and took up serialism. The shock waves reverberated around the Western musical world. It was as if the commanding general of one army had gone over to the enemy. Stravinsky's historic turn certified the triumph of serialism and the avant-garde in the forefront of new music. The revolutionists took over the shop. Two generations of neoclassicists found themselves out of the spotlight and sometimes out of a job. Aaron Copland, who had started his career as an avant-gardist in the 20s before turning to his more populist style, took up serialism in the 1950s. A third train of thought in music seemed to contradict all other camps. In his 1949 "Lecture on Nothing," composer John Cage declared, "I have nothing to say/ and I am saying it/ and that is poetry/ as I need it." In the spirit of a Zen openness to the world, Cage rejected the whole past agenda of music: logic, emotion, meaning, beauty, form, and on and on. Any sound whatever (and even better, silence) he declared to be music. Cage began to compose by chance methods involving throwing dice, turning on radios, consulting the I Ching. As much as a new aesthetic, Cage's music was another response to the horrors of the immediate past: Germany's turn to barbarism; the historic mapping of atomic structure being utilized to make a new and deadlier bomb. Perhaps Cage summarized the social and political undercurrent of his art when he wrote "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)." Cage and his disciples came to be called the aleatoric movement (from the Latin alea , dice). It had wide influence; for some, the pursuit of meaninglessness appeared to be a way out of the disastrous ideologies and agendas of the past. It would seem that the aleatoric ethos would be ultimately contrary to the serial school. In practice, however, there grew up a rapprochement between serialists and aleatoricists. After all, they made similar kinds of sounds, they worked outside the mainstream of concert life, they were all generally denoted "avant-garde," they often had an attitude of indifference unto hostility toward the bourgeois concert-going public and to popular culture. All this had an air of authenticity and inevitability. For many postwar composers in Europe and America, after the manifest death of the old tonal system, serialism appeared the only alternative to musical anarchy, and the avant-garde the best antidote to cultural boredom and stagnation. But as the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, an abiding problem refused to go away: Not enough people were buying tickets to hear avant-garde or serial music. By then much of Stravinsky was standard repertoire, Bartók was catching on, Paul Hindemith was alive and working and often performed (and had many disciples of his own). But despite occasional successes, the revolutionary side of the musical equation could not find its way into the mainstream. Then came the Vietnam War, and in its aftermath a new wave of revolution and reaction—the political reaction still ongoing as of 2012. Perhaps inevitably, among younger American composers there rose a rebellion against the last generation's rebellion. In 1964, as the "counterculture" emerged and beards and protests sprouted across the U.S., Terry Riley wrote a chirping, hypnotic, semi-aleatoric piece called In C . That work and its fellows of what came to be called the minimalist school, its other leading figures Steve Reich and Philip Glass, fled as far as possible from academic serialism to an utter simplicity and transparency of means. Minimalism's relentless babble and beat rose, among other sources, from pop music. The success of minimalism had the effect of opening up a gigantic tract of musical territory between serialist arcana on one hand and five-note, hour-long minimalism on the other. Most composers of the last forty years work somewhere in that middle territory. At the same time, from the 60s the once somewhat well-defined realms of "popular," "classical," and "avant-garde" music began to merge. They have been merging ever since. In 1974, the great Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu, visiting at Yale, told me: "We are free now." He meant free from ideologies of tonal vs. atonal, of stylistic consistency, even of popular vs. classical. It was in the same period that another composer said, approximately, "It's hard to make a revolution when, two revolutions ago, they already said anything goes." It was in the 1960s and 70s that the music of Charles Ives, who declared that the old ideas of unity and style were inadequate, and who composed everything from Victorian parlor songs to the wildest pandemonium, emerged fully into public awareness. The career of Yehudi Wyner, another composer heard this summer in Aspen, might stand for the evolution of a good many of his generation. A student of Hindemith among others, Wyner began in the neoclassic school; in the mid-50s he was writing in a more chromatic and exploratory vein. By the 70s his music had become more forthrightly emotional. In 2006 his passionately expressive piano concerto Chiavi in mano , which he calls "a particularly 'American' piece," won the Pulitzer Prize. All of Wyner's past lies in that concerto. In the 1980s composer Jacob Druckman suggested a trend of New Romanticism in the music he was hearing by composers including David del Tredici, some of whose Alice in Wonderland pieces recall Richard Strauss. The end-of-century postmodern movement seemed to revel in the impossibility of doing anything truly new. Postmodern artists indulge in ironic games with the past, mixing and matching and mismatching among the arts once divided into "high" and "low." Some of these trends came equipped with heavy theoretical baggage, some were more playful and frankly audience-grabbing. Now in any case, mainly because of mass media, there is less natural flow and ebb of artistic movements. Every movement tends to stick around indefinitely, just as current campus fashions trace a spectrum of clothing and hairstyles from the 50s on. In effect, what the serialists of the 1950s feared came to pass: Musical composition along with the other arts evolved into a kind of dynamic anarchy that voraciously consumes every movement of the past. Part of what gave rise to this situation was the ubiquity of modern media, which preserves everything. It becomes harder to envision the future when the past is before our eyes and ears all the time. More recent developments, as they always do, have taken contrasting directions. On the one hand there is a kind of post-punk rambunctiousness that has been dubbed "aesthetic brutalism." On the other side there are the composers grouped around Robert Spano and the Atlanta Symphony, dubbed the "Atlanta School." Here is a group that offers listeners a warm embrace. Among them are Jennifer Higdon, whose lushly neoromantic Violin Concerto won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize, and Boston's Michael Gandolfi—both of them represented in Aspen this summer. Their contemporary George Tsontakis, a long-time Aspen fixture, has pursued an individual path, much of it originating in his Greek heritage. A school of spectralist composers explore new kinds of musical organization based on the acoustical properties of sound. Thus my flyover of the last half century in American music. How to summarize it? The best way I can think of is as follows. I teach at The Boston Conservatory, in which there are currently 33 student composers and five composition teachers, and these 38 composers write in 38 distinct ways. When I am teaching and want to make a point or give an illustration to a student, I often turn to the computer and call up a piece that might be anything from Bruckner to Bartók to Christopher Rouse to Bulgarian folk music. Sometimes these pieces have a galvanizing effect on the student's work. Of the composers older and younger at my school, none are writing exclusively serial music, none are mainstream minimalists, none are regularly involved with aleatoric procedures, none sound much like Schoenberg or Stravinsky, many write both tonal and atonal pieces, only a few are detectably neoromantic or postmodern or close to the 60s-70s avant-garde. Yet every one of those influences are present in our work, in kaleidoscopic and unpredictable ways. That is what I mean by "dynamic anarchy." It has its dangers, but also its potentials. How do I as a composer and writer add all this up? I don't know that it's possible to. Nor do I have any prognostications for the future. Music is here to enjoy, to love, to be fascinated and moved and amused and scared and exalted by. I believe that a composer's job is to provide those experiences for us. If and when audiences for "classical" music are ready to be moved and exalted by myriad voices and languages, when audiences are ready to be as excited about hearing something new as they were in Mozart's day—then music will thrive. The works from the last fifty years in this summer's Aspen concerts are part of the ongoing experiment in that direction.

Sorry, there was a problem. Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required . Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web. Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.  Image Unavailable

Follow the author Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph Paperback – January 1, 2014

Products related to this item Product details

About the authorJan swafford. Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more  Customer reviews