Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Faculty of Health, University of Applied Sciences Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands, Clinical Neurodevelopmental Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Faculty of Health, University of Applied Sciences Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands, KenVak, Research Centre for the Arts Therapies, Heerlen, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations KenVak, Research Centre for the Arts Therapies, Heerlen, The Netherlands, Centre for the Arts Therapies, Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, Heerlen, The Netherlands, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Open University, Heerlen, The Netherlands

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Clinical Neurodevelopmental Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Health, University of Applied Sciences Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands

- Annemarie Abbing,

- Anne Ponstein,

- Susan van Hooren,

- Leo de Sonneville,

- Hanna Swaab,

- Published: December 17, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

- Reader Comments

Anxiety disorders are one of the most diagnosed mental health disorders. Common treatment consists of cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy. In clinical practice, also art therapy is additionally provided to patients with anxiety (disorders), among others because treatment as usual is not sufficiently effective for a large group of patients. There is no clarity on the effectiveness of art therapy (AT) on the reduction of anxiety symptoms in adults and there is no overview of the intervention characteristics and working mechanisms.

A systematic review of (non-)randomised controlled trials on AT for anxiety in adults to evaluate the effects on anxiety symptom severity and to explore intervention characteristics, benefitting populations and working mechanisms. Thirteen databases and two journals were searched for the period 1997 –October 2017. The study was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42017080733) and performed according to the Cochrane recommendations. PRISMA Guidelines were used for reporting.

Only three publications out of 776 hits from the search fulfilled the inclusion criteria: three RCTs with 162 patients in total. All studies have a high risk of bias. Study populations were: students with PTSD symptoms, students with exam anxiety and prisoners with prelease anxiety. Visual art techniques varied: trauma-related mandala design, collage making, free painting, clay work, still life drawing and house-tree-person drawing. There is some evidence of effectiveness of AT for pre-exam anxiety in undergraduate students. AT is possibly effective in reducing pre-release anxiety in prisoners. The AT characteristics varied and narrative synthesis led to hypothesized working mechanisms of AT: induce relaxation; gain access to unconscious traumatic memories, thereby creating possibilities to investigate cognitions; and improve emotion regulation.

Conclusions

Effectiveness of AT on anxiety has hardly been studied, so no strong conclusions can be drawn. This emphasizes the need for high quality trials studying the effectiveness of AT on anxiety.

Citation: Abbing A, Ponstein A, van Hooren S, de Sonneville L, Swaab H, Baars E (2018) The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS ONE 13(12): e0208716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

Editor: Vance W. Berger, NIH/NCI/DCP/BRG, UNITED STATES

Received: July 15, 2018; Accepted: November 22, 2018; Published: December 17, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Abbing et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All files are available from https://tinyurl.com/yamju5x5 .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are disorders with an ‘abnormal’ experience of fear, which gives rise to sustained distress and/ or obstacles in social functioning [ 1 ]. Among these disorders are panic disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). The prevalence of anxiety disorders is high: 12.0% in European adults [ 2 ] and 10.1% in the Dutch population [ 3 ]. Lifetime prevalence for women ranges from 16.3% [ 2 , 4 ] to 23.4% [ 3 ] and for men from 7.8% to 15.9% [ 2 , 3 ] in Europe. It is the most diagnosed mental health disorder in the US [ 5 ] and incidence levels have increased over the last half of the 20 th century [ 6 ].

Anxiety disorders rank high in the list of burden of diseases. According to the Global Burden of Disease study [ 7 ], anxiety disorders are the sixth leading cause of disability, in terms of years lived with disability (YLDs), in low-, middle- and high-income countries in 2010. They lead to reduced quality of life [ 8 ] and functional impairment, not only in personal life but also at work [ 4 , 9 , 10 ] and are associated with substantial personal and societal costs [ 11 ].

The most common treatments of anxiety disorders are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/ or pharmacotherapy with benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [ 1 ]. These treatments appear to be only moderately effective. Pharmacological treatment causes side effects and a significant percentage of patients (between 20–50% [ 12 – 15 ] is unresponsive or has a contra-indication. Combination with CBT is recommended [ 16 ] but around 50% of patients with anxiety disorders do not benefit from CBT [ 17 ].

To increase the effectiveness of treatment of anxiety disorders, additional therapies are used in clinical practice. An example is art therapy (AT), which is integrated in several mental health care programs for people with anxiety (e.g. [ 18 , 19 ]) and is also provided as a stand-alone therapy. AT is considered an important supportive intervention in mental illnesses [ 20 – 22 ], but clarity on the effectiveness of AT is currently lacking.

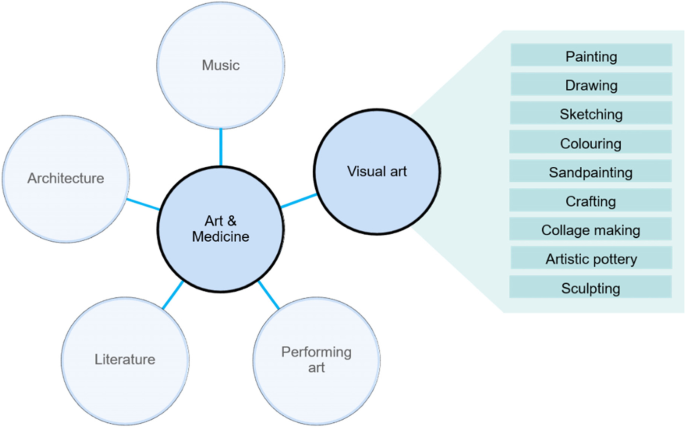

AT uses fine arts as a medium, like painting, drawing, sculpting and clay modelling. The focus is on the process of creating and (associated) experiencing, aiming for facilitating the expression of memories, feelings and emotions, improvement of self-reflection and the development and practice of new coping skills [ 21 , 23 , 24 ].

AT is believed to support patients with anxiety in coping with their symptoms and to improve their quality of life [ 20 ]. Based on long-term experience with treatment of anxiety in practice, AT experts describe that AT can improve emotion regulation and self-structuring skills [ 25 – 27 ] and can increase self-awareness and reflective abilities [ 28 , 29 ]. According to Haeyen, van Hooren & Hutschemakers [ 30 ], patients experience a more direct and easier access to their emotions through the art therapies, compared to verbal approaches. As a result of these experiences, AT is believed to reduce symptoms in patients with anxiety.

Although AT is often indicated in anxiety, its effectiveness has hardly been studied yet. In the last decade some systematic reviews on AT were published. These reviews covered several areas. Some of the reviews focussed on PTSD [ 31 – 34 ], or have a broader focus and include several (mental) health conditions [ 35 – 39 ]. Other reviews included AT in a broader definition of psychodynamic therapies [ 40 ] or deal with several therapies (CBTs, expressive art therapies (e.g., guided imagery and music therapy), exposure therapies (e.g., systematic desensitization) and pharmacological treatments within one treatment program) [ 41 ].

No review specifically aimed at the effectiveness of AT on anxiety or on specific anxiety disorders. For anxiety as the primary condition, thus not related to another primary disease or condition (e.g. cancer or autism), there is no clarity on the evidence nor of the employed therapeutic methods of AT for anxiety in adults. Furthermore, clearly scientifically substantiated working mechanism(s), explaining the anticipated effectiveness of the therapy, are lacking.

The primary objective is to examine the effectiveness of AT in reducing anxiety symptoms.

The secondary objective is to get an overview of (1) the characteristics of patient populations for which art therapy is or may be beneficial, (2) the specific form of ATs employed and (3) reported and hypothesized working mechanisms.

Protocol and registration

The systematic review was performed according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration for study identification, selection, data extraction, quality appraisal and analysis of the data [ 42 ]. The PRISMA Guidelines [ 43 ] were followed for reporting ( S1 Checklist ). The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO, number CRD42017080733 [ 44 ]. The AMSTAR 2 checklist was used to assess and improve the quality of the review [ 45 ].

Eligibility criteria

Types of study designs..

The review included peer reviewed published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised controlled trials (nRCTs) on the treatment of anxiety symptoms. nRCTs were also included because it was hypothesized that nRCTs are more executed than RCTs, for the research field of AT is still in its infancy.

Only publications in English, Dutch or German were included. These language restrictions were set because the reviewers were only fluent in these three languages.

Types of participants.

Studies of adults (18–65 years), from any ethnicity or gender were included.

Types of interventions.

AT provided to individuals or groups, without limitations on duration and number of sessions were included.

Types of comparisons.

The following control groups were included: 1) inactive treatment (no treatment, waiting list, sham treatment) and 2) active treatment (standard care or any other treatment). Co-interventions were allowed, but only if the additional effect of AT on anxiety symptom severity was measured.

Types of outcome measures.

Included were studies that had reduction of anxiety symptoms as the primary outcome measure. Excluded were studies where reduction of anxiety symptoms was assessed in non-anxiety disorders or diseases and studies where anxiety symptoms were artificially induced in healthy populations. Populations with PTSD were not excluded, since this used to be an anxiety disorder until 2013 [ 46 ].

The following 13 databases and two journals were searched: PUBMED, Embase (Ovid), EMCare (Ovid), PsychINFO (EBSCO), The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects, Web of Science, Art Index, Central, Academic Search Premier, Merkurstab, ArtheData, Reliëf, Tijdschrift voor Vaktherapie.

A search strategy was developed using keywords (art therapy, anxiety) for the electronic databases according to their specific subject headings or structure. For each database, search terms were adapted according to the search capabilities of that database ( S1 File Full list of search terms).

The search covered a period of twenty years: 1997 until October 9, 2017. The reference lists of systematic reviews—found in the search—were hand searched for supplementing titles, to ensure that all possible eligible studies would be detected.

Study selection

A single endnote file of all references identified through the search processes was produced. Duplicates were removed.

The following selection process was independently carried out by two researchers (AA and AP). In the first phase, titles were screened for eligibility. The abstracts of the remaining entries were screened and only those that met the inclusion criteria were selected for full text appraisal. These full texts were subsequently assessed according to the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement in study selection between the two independent reviewers was resolved through discussion or by consultation of a third reviewer (EB).

Data collection process

The data were extracted by using a data extraction spreadsheet, based on the Cochrane Collaboration Data Collection Form for intervention reviews ( S1 Table Data collection form).

The form concerned the following data: aim of the study, study type, population, number of treated subjects, number of controlled subjects, AT description, duration, frequency, co-intervention(s), control description, outcome domains and outcome measures, time points, outcomes and statistics.

After separate extraction of the data, the results of the two independent assessors were compared and discussed to reach consensus.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The risk of bias (RoB) was independently assessed by the two reviewers with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing RoB [ 47 ]. Bias was assessed over the domains: selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of researchers conducting outcome assessments), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting). A judgement of ‘low’, ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ risk of bias was provided for each domain. Since the RoB tool was developed for use in pharmacological studies, we followed the recommendations of Munder & Barth [ 48 ] that placed the RoB tool in the context of psychotherapy outcome research. Performance bias is defined here as "studies that did not use active control groups or did not assess patient expectancies or treatment credibility", instead of only 'blinding of participants and personnel'.

A summary assessment of RoB for each study was based on the approach of Higgins & Green [ 47 ]: overall low RoB (low risk of bias in all domains), unclear RoB (unclear RoB in at least one domain) and high RoB (unclear RoB in more than one domain or high RoB in at least one domain).

The primary outcome measure was anxiety symptoms reduction (pre-post treatment). The outcomes are presented in terms of differences between intervention and control groups (e.g., risk ratios or odds ratios). Within-group outcomes are also presented, to identify promising outcomes and hypotheses for future research.

Data from studies were combined in a meta-analyses to estimate overall effect sizes, if at least two studies with comparable study populations and treatment were available that assessed the same specific outcomes. Heterogeneity was examined by calculating the I 2 statistic and performing the Chi 2 test. If heterogeneity was considered relevant, e.g. I 2 statistic greater than 0.50 and p<0.10, sources of heterogeneity were investigated, subanalyses were performed as deemed clinically relevant, and subtotals only, or single trial results were reported. In case of a meta-analysis, publication bias was assessed by drawing a funnel plot based on the primary outcome from all trials and statistical analysis of risk ratios or odds ratios as the measure of treatment effect.

A content analysis was conducted on the characteristics of the employed ATs, the target populations and the reported or hypothesized working mechanisms.

Quality of evicence

Quality (or certainty) of evidence of the studies with significant outcomes only was was assessed with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [ 49 ]. Evidence can be scored as high, moderate, low or very low, according to a set of criteria.

The search yielded 776 unique citations. Based on title and abstract, 760 citations were excluded because the language was not English, Dutch or German (n = 23), were not about anxiety (n = 164), or it concerned anxiety related to another primary disease or condition (n = 175), didn’t concern adults (18–65 years) (n = 152), were not about AT (n = 94), were not a controlled trial (n = 131), or were lacking a control group (n = 22) or anxiety symptoms were not used as outcome measure (n = 1).

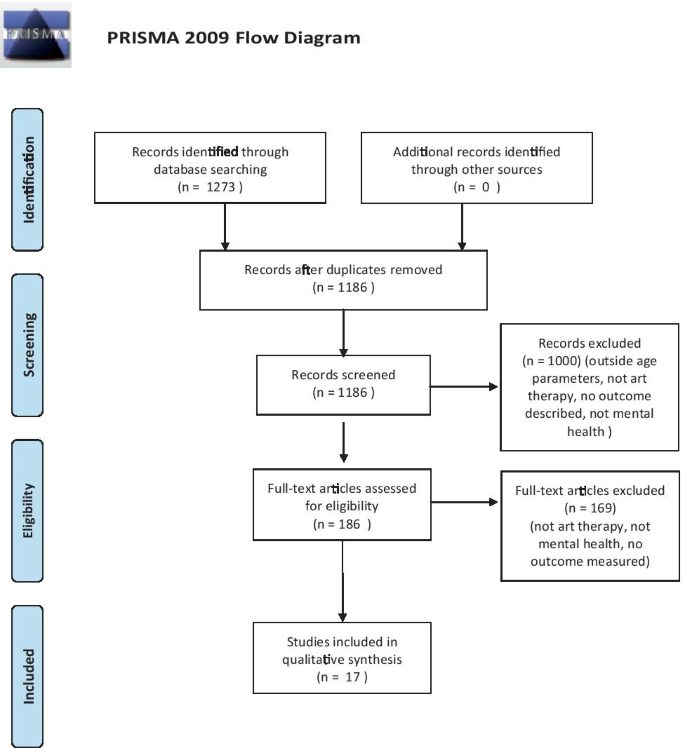

Of the remaining 16 full text articles, 13 articles were excluded. Reasons were: lack of a control group [ 50 – 54 ], anxiety was related to another primary disease or condition [ 55 , 56 ], or the study population consisted of healthy subjects [ 57 , 58 ], did not concern subjects in the age between 18–65 years [ 59 ], or was not peer-reviewed [ 60 ] or did not have pre-post measures of anxiety symptom severity [ 61 , 62 ]. A list of all potentially relevant studies that were excluded from the review after reading full-texts, is presented in S2 Table Excluded studies with reasons for exclusion . Finally, three studies were included for the systematic review ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.g001

Screening of references from systematic reviews.

The systematic literature search yielded 15 systematic reviews. All titles from the reference lists of these reviews were screened (n = 999), of which 27 publications were eligible for abstract screening and were other than the 938 citations found in the search described above (see Study selection). From these abstracts, 18 were excluded because they were not peer reviewed (n = 3), not in English, Dutch or German (n = 1), not about anxiety (n = 2), or were about anxiety related to cancer (n = 2), were not about AT (n = 2) or were not a controlled trial (n = 8). Nine full texts were screened for eligibility and were all excluded. Six full texts were excluded because these concerned psychodynamic therapies and did not include AT [ 63 – 68 ]. Two full texts were excluded because they concerned multidisciplinary treatment and no separate effects of AT were measured [ 18 , 19 ]. The final full text was excluded because it concerned induced worry in a healthy population [ 69 ]. No studies remained for quality appraisal and full review. The justified reasons for exclusion of all potentially relevant studies that were read in full-text form, is presented in S2 Table Excluded studies with reasons for exclusion .

Study characteristics

The review includes three RCTs. The study populations of the included studies are: students with PTSD symptoms and two groups of adults with fear for a specific situation: students prior to exams and prisoners prior to release. The trials have small to moderate sample sizes, ranging from 36 to 69. The total number of patients in the included studies is 162 ( Table 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.t001

In one study, AT is combined with another treatment: a group interview [ 72 ]. The other two studies solely concern AT ( Table 2 ) [ 70 , 71 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.t002

The provided AT varies considerably: mandala creation in which the trauma is represented [ 70 ] or colouring a pre-designed mandala, free clay work, free form painting, collage making, still life drawing [ 71 ], and house-tree-person drawings (HTP) [ 72 ]. Session duration differs from 20 minutes to 75 minutes. The therapy period ranges from only once to eight weeks, with one to ten sessions in total ( Table 2 ). In one study, the control group receives the co-intervention only: group interview in Yu et al. [ 72 ]. Henderson et al. [ 70 ] use three specific drawing assignments as control condition, which are not focussed on trauma, opposed to the provided art therapy in the experimental group. Sandmire et al. [ 71 ] used inactive treatment. Here, AT is compared to comfortably sitting. Study settings were outpatient: universities (US) and prison (China). None of the RCTs reported on sources of funding for the studies.

See S3 Table for an extensive overview of characteristics and outcomes of the included studies.

Risk of bias within studies

Based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias, estimations of bias were made. Table 3 shows that the risk of bias (RoB) is high in all studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.t003

Selection bias : overall, methods of randomization were not always described and selection bias can therefore not be ruled out, which leads to unclear RoB. Henderson et al. [ 70 ] described the randomisation of participants over experimental and control groups. However, it is unclear how gender and type of trauma are distributed. Sandmire et al. [ 71 ] did not describe the randomization method but there was no baseline imbalance. Also Yu et al. [ 72 ] did not decribe the randomisation method, but two comparable groups were formed as concluded on baseline measures. Nevertheless it is unclear whether psychopathology of control and experimental groups are comparable.

Performance bias : Sandmire’s RCT had inactive control, which gives a high risk on performance bias [ 48 ]. Like in psychotherapy outcome research, blinding of patients and therapists is not feasible in AT [ 48 , 73 ]. It is not possible to judge whether the lack of blinding influenced the outcomes and also none of the studies assessed treatment expectancies or credibility prior to or early in treatment, so all studies were scored as ‘high risk’ on performance bias.

Detection bias : in all studies only self-report questionnaires were used. The questionnaires used are all validated, which allows a low risk score of response bias. However, the exact circumstances under which measures are used are not described [ 70 , 71 ] and may have given rise to bias. Presence of the therapist and or fear for lack of anonymity may have influenced scores and may have led to confirmation bias (e.g.[ 74 ]), which results in a ‘unclear’ risk of detection bias.

Attrition bias : in the study of Henderson it is not clear whether the outcome dataset is complete.

Reporting bias : there are no reasons to expect that there has been selective reporting in the studies.

Other issues : in Sandmire et al. [ 71 ] it was noted that the study population constists of liberal arts students, who are likely to have positive feelings towards art making and might expericence more positive effects (reduction of anxiety) than students from other disciplines.

Overall risk of bias : since all studies had one or more domains with high RoB, the overall RoB was high.

Outcomes of individual studies

The measures used in the studies are shown in Table 4 . The outcome measures for anxiety differ and include the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (used in two studies), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) and the Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (used in one study). Quality of life was not measured in any of the included studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.t004

Anxiety–in study with inactive control.

Sandmire et al. [ 71 ] showed significant between-group effects of art making on state anxiety (tested with ANOVA: experimental group (mean (SD)): 39.3 (9.4) - 29.5 (8.6); control group (mean (SD)): 36.2 (8.8) - 36.0 (10.9)\; p = 0.001) and on trait anxiety (experimental group (mean (SD)): 39.1 (5.8) - 33.3 (6.1); control group (mean (SD)): 38.2 (10.2) - 37.3 (11.2); p = 0.004) There were no significant differences in effectiveness between the five types of art making activities.

Anxiety–in studies with active control.

Henderson et al. [ 70 ] reported no significant effect of creating mandalas (trauma-related art making) versus random art making on anxiety symptoms (tested with ANCOVA: experimental group (mean (SD)): 45.05 (10.75) - 41.16 (11.30); control group (mean (SD): 49.05 (12.29) - 44.05 (10.12), p -value: not reported) immediately after treatment. At follow-up after one month there was also no significant effect of creating mandalas on anxiety symptoms: experimental group (mean (SD): 40.95 (11.54); control group (mean (SD): 42.0 (13.26)), but there was significant improvement of PTSD symptom severity at one-month follow-up ( p = 0.015).

Yu et al. (2016) did not report analyses of between-group effects. Only the experimental group, who made HTP drawings followed by group interview, showed a significant pre- versus post-treatment reduction of anxiety symptoms (two-tailed paired sample t-tests: HAM-A (mean (SD): 24.36 (9.11) - 17.42 (10.42), p = 0.001; SAS (mean (SD): 62.63 (9.46) - 56.78 (11.64,) p = 0.004). The anxiety level in the control group on the other hand, who received only group interview, increased between pre- and post-treatment (HAM-A (mean (SD): 24.75 (6.14) - 25.22 (7.37), not significant; SAS (mean (SD): 62.57 (7.36) - 66.11 (10.41), p = 0.33).

Summary of outcomes and quality.

Of three included RCTs studying the effects of AT on reducing anxiety symptoms, one RCT [ 71 ] showed a significant anxiety reduction, one RCT [ 72 ] was inconclusive because no between-group outcomes were provided, and one RCT [ 70 ] found no significant anxiety reduction, but did find signifcant reduction of PTSD symptoms at follow-up.

Regarding within-group differences, two studies [ 71 , 72 ] showed significant pre-posttreatment reduction of anxiety levels in the AT groups and one did not [ 70 ].

The quality of the evidence in Sandmire [ 71 ] as assessed with the GRADE classification is low to very low (due to limited information the exact classification could not be determined). The crucial risk of bias, which is likely to serious alter the results [ 49 ], combined the with small sample size (imprecision [ 75 ]) led to downgrading of at least two levels.

Meta-analysis.

Because data were insufficiently comparable between the included studies due to variation in study populations, control treatments, the type of AT employed and the use of different measures, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Narrative synthesis

Benefiting populations..

AT seems to be effective in the treatment of pre-exam anxiety (for final exams) in adult liberal art students [ 71 ], although the quality of evidence is low due to high RoB. Based on pre-posttreatment anxiety reduction (within-group analysis) AT may be effective for adult prisoners with pre-release anxiety [ 72 ].

Characteristics of AT for anxiety.

Sandmire et al. [ 71 ] gave students with pre-exam stress one choice out of five art-making activities: mandala design, free painting, collage making, free clay work or still life drawing. The activity was limited to one session of 30 minutes. This was done in a setting simulating an art center where students could use art materials to relieve stress. The mandala design activity consisted of a pre-designed mandala which could be completed by using pencils, tempera paints, watercolors, crayons or markers. The free form painting activity was carried out on a sheet of white paper using tempera or water color paints which were used to create an image from imagination. Participants could also use fine-tip permanent makers, crayons, colored pencils and pastels to add detailed design work upon completion of the initial painting. Collage making was also one of the five options. This was done with precut images and text, by further cutting out the images and additonal images from provided magazins and gluing them on a white piece of paper. Participants could also choose for a clay activity to make a ‘pleasing form’. Examples were a pinch pot, coil pot and small animal figures. The final option for art-making was a still life drawing, by arranging objects into a pleasing assembly and drafting with pencil. Additionally, diluted sepia ink could be used to paint in tonal values.

Yu et al. [ 72 ] used the HTP drawings in combination with group interviews about the drawings, to treat pre-release anxiety in male prisoners. The procedure consists of drawing a house, a tree and a person as well as some other objects on a sheet of paper. Yu follows the following interpretation: the house is regarded as the projection of family, the tree represents the environment and the person represents self-identification [ 76 ]. The HTP drawing is usually used as a diagnostic tool, but is used in this study as an intervention to enable prisoners to become more aware of their emotional issues and cognitions in relation to their upcoming release. A counselor gives helpful guidance based on the drawing and reflects on informal or missing content, so that the drawings can be enriched and completed. After completion of the drawings, prisoners participated in a group interview in which the unique attributes of the drawings are related to their personal situation and upcoming release.

Henderson et al. [ 70 ] treated traumatised students with mandala creation, aiming for the expression and representation of feelings. The participants were asked to draw a large circle and to fill the circle with feelings or emotions related to their personal trauma. They could use symbols, patterns, designs and colors, but no words. One session lasted 20 minutes and the total intervention consisted of three sessions, on three consecutive days. One month after the intervention, the participants were asked about the symbolic meaning of the mandala drawings.

Working mechanisms of AT.

Sandmire used a single administration of art making to treat the handling of stressful situations (final exams) of undergraduate liberal art students. The art intervention did not explicitly expose students to the source of stress, hence a general working mechanism of AT is expected. The authors claim that art making offers a bottom-up approach to reduce anxiety. Art making, in a non-verbal, tactile and visual manner, helps entering a flow-like-state of mind that can reduce anxiety [ 77 ], comparable to mindfulness.

Yu reports that nonverbal symbolic methods, like HTP-drawing, are thought to reflect subconscious self-relevant information. The process of art making and reflection upon the art may lead to insights in emotions and (wrong) cognitions that can be addressed during counseling. The authors state that “HTP-drawing is a natural, easy mental intervention technique through which counselors can guide prisoners to form helpful cognitions and behaviors within a relative relaxing and well-protected psychological environment”. In this case the artwork is seen as a form of unconscious self-expression that opens up possibilities for verbal reflections and counseling. In the process of drawing, the counselor gives guidance so the drawing becomes more complete and enriched, what possibly entails a positive change in the prisoners’ cognitive patters and behavior.

Henderson treated PTSD symptoms in students and expected the therapy to work on anxiety symptoms as well. The AT intervention focussed on the creative expression of traumatic memories, which can been seen as an indirect approach to exposure, with active engagement. The authors indicate that mandala creation (related to trauma) leads to changes in cognition, facilitating increasing gains. Exposure, recall and emotional distancing may be important attributes to recovery.

Summarizing, three different types of AT can be distinguised: 1) using art-making as a pleasant and relaxing activity; 2) using art-making for expression of (unconsious) cognitive patterns, as an insightful tool; and 3) using the art-making process as a consious expression of difficult emotions and (traumatic) memories.

Based on these findings, we can hypothesize that AT may contribute to reducing anxiety symptom severity, because AT may:

- induce relaxation, by stimulating a flow-like state of mind, presumably leading to a reduction of cortisol levels and hence stress and anxiety reduction (stress regulation) [ 71 ];

- make the unconscious visible and thereby creating possibilities to investigate emotions and cognitions, contributing to cognitive regulation [ 70 , 72 ].

- create a safe environment for the conscious expression of (difficult) emotions and memories, what is similar to exposure, recall and emotional distancing, possibly leading to better emotion regulation [ 70 ].

Currently there is no overview of evidence of effectiveness of AT on the reduction of anxiety symptoms and no overview of the intervention characteristics, the populations that might benefit from this treatment and the described and/ or hypothesized working mechanisms. Therefore, a systematic review was performed on RCTs and nRCTs, focusing on the effectiveness of AT in the treatment of anxiety in adults.

Summary of evidence and limitations at study level

Three publications out of 776 hits of the search met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. No supplemented publications from the reference lists (999 titles) of 15 systematic reviews on AT could be included. Considering the small amount of studies, we can conclude that effectiveness research on AT for anxiety in adults is in a beginning state and is developing.

The included studies have a high risk of bias, small to moderate sample sizes and in total a very small number of patients (n = 162). As a result, there is no moderate or high quality evidence of the effectiveness of AT on reducing anxiety symptom severity. Low to very low-quality of evidence is shown for AT for pre-exam anxiety in undergraduate students [ 71 ]. One RCT on prelease anxiety in prisoners [ 72 ] was inconclusive because no between-group outcome analyses were provided, and one RCT on PTSD and anxiety symptoms in students [ 70 ] found significant reduction of PTSD symtoms at follow-up, but no significant anxiety reduction. Regarding within-group differences, two studies [ 71 , 72 ] showed significant pre-posttreatment reduction of anxiety levels in the AT groups and one did not [ 70 ]. Intervention characteristics, populations that might benefit from this treatment and working mechanisms were described. In conclusion, these findings lead us to expect that art therapy may be effective in the treatment of anxiety in adults as it may improve stress regulation, cognitive regulation and emotion regulation.

Strengths and limitations of this review

The strength of this review is firstly that it is the first systematic review on AT for primary anxiety symptoms. Secondly, its quality, because the Cochrane systematic review methodology was followed, the study protocol was registered before start of the review at PROSPERO, the AMSTAR 2 checklist was used to assess and improve the quality of the review and the results were reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. A third strength is that the search strategy covers a long period of 20 years and a large number of databases (13) and two journals.

A first limitation, according to assessment with the AMSTAR 2 checklist, is that only peer reviewed publications were included, which entails that many but not all data sources were included in the searches. Not included were searches in trial/study registries and in grey literature, since peer reviewed publication was an inclusion criterion. Content experts in the field were also not consulted. Secondly, only three RCTs met the inclusion criteria, each with a different target population: students with moderate PTSD, students with pre-exam anxiety and prisoners with pre-release anxiety. This means that only a small part of the populations of adults with anxiety (disorders) could be studied in this review. A third (possible) limitation concerns the restrictions regarding the included languages and search period applied (1997- October 2017). With respect to the latter it can be said that all included studies are published after 2006, making it likely that the restriction in search period has not influenced the outcome of this review. No studies from 1997 to 2007 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This might indicate that (n)RCTs in the field of AT, aimed at anxiety, are relatively new. A fourth limitation is the definition of AT that was used. There are many definitions for AT and discussions about the nature of AT (e.g. [ 78 ]). We considered an intervention to be art therapy in case the visual arts were used to promote health/wellbeing and/or the author called it art therapy. Thus, only art making as an artistic activity was excluded. This may have led to unwanted exclusion of interesting papers.

A fifth limitation is the use of the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence of art therapy studies. This tool is developed for judging quality of evidence of studies on pharmacological treatments, in which blinding is feasible and larger sample sizes are accustomed. However the assessed study was a RCT on art therapy [ 71 ], in which blinding of patients and therapists was not possible. Because the GRADE approach is not fully tailored for these type of studies, it was difficult to decide whether the the exact classification of the available evidence was low or very low.

Comparison to the AT literature

The results of the review are in agreement with other findings in the scientific literature on AT demonstrating on the one hand promising results of AT and on the other hand showing many methodological weaknesses of AT trials. For example, other systematic reviews on AT also report on promising results for art therapy for PTSD [ 31 – 34 , 37 ] and for a broader range of (mental) health conditions [ 35 – 39 ], but since these reviews also included lower quality study designs next to RCTs and nRCTs, the quality of this evidence is likely to be low to very low as well. These reviews also conclude on methodological shortcomings of art therapy effectiveness studies.

Three approaches in AT were identified in this review: 1) using art-making as a relaxing activity, leading to stress reduction; 2) using the art-making process as a consious pathway to difficult emotions and (traumatic) memories; leading to better emotion regulation; and 3) using art-making for expression, to gain insight in (unconscious) cognitive patterns; leading to better cognitive regulation.

These three approaches can be linked to two major directions in art therapy, identified by Holmqvist & Persson [ 74 ]: “art-as-therapy” and “art-in-psychotherapy”. Art-as-therapy focuses on the healing ability and relaxing qualities of the art process itself and was first described by Kramer in 1971 [ 79 ]. This can be linked to the findings in the study of Sandmire [ 71 ], where it is suggested that art making led to lower stress levels. Art making is already associated with lower cortisol levels [ 80 ]. A possible explanation for this finding can be that a trance-like state (in flow) occurs during art-making [ 81 ] due to the tactile and visual experience as well as the repetitive muscular activity inherent to art making.

Art-in-psychotherapy , first described by Naumberg [ 82 ] encompasses both the unconscious and the conscious (or semi-conscious) expression of inner feelings and experiences in apparently free and explicit exercises respectively. The art work helps a patient to open up towards their therapist [ 74 ], so what the patient experienced during the process of creating the art work, can be deepened in conversation. In practice, these approaches often overlap and interweave with one another [ 83 ], which is probably why it is combined in one direction ‘art-in-psychotherapy’. It might be beneficial to consider these ways of conscious and unconscious expression separately, because it is a fundamental different view on the importance of art making.

The overall picture of the described and hypothesized working mechanisms that emerged in this review lead to the hypotheses that anxiety symptoms may decrease because AT may support stress regulation (by inducing relaxation, presumably comparable to mindfulness [ 64 , 84 ], emotion regulation (by creating the safe condition for expression and examination of emotions) and cognitive regulation (as art work opens up possibilities to investigate (unconscious) cognitions). These types of regulation all contribute to better self-regulation [ 85 ]. The hypothesis with respect to stress regulation is further supported by results from other studies. The process of creating art can promote a state of mindfulness [ 57 ]. Mindfulness can increase self-regulation [ 84 ] which is a moderator between coping strength and mental symptomatology [ 86 ]. Improving patient’s self-regulation leads, amongst others, to improvement of coping with disease conditions like anxiety [ 85 , 86 ]. Our findings are in accordance with the findings of Haeyen [ 30 ], stating that patients learn to express emotions more effectively, because AT enables them to “examine feelings without words, pre-verbally and sometimes less consciously”, (p.2). The connection between art therapy and emotion regulation is also supported by the recently published narrative review of Gruber & Oepen [ 87 ], who found significant effective short-term mood repair through art making, based on two emotion regulation strategies: venting of negative feelings and distraction strategy: attentional deployment that focuses on positive or neutral emotions to distract from negative emotions.

Future perspectives

Even though this review cannot conclude effectiveness of AT for anxiety in adults, that does not mean that AT does not work. Art therapists and other care professionals do experience the high potential of AT in clinical practice. It is challenging to find ways to objectify these practical experiences.

The results of the systematic review demonstrate that high quality trials studying effectiveness and working mechanisms of AT for anxiety disorders in general and specifically, and for people with anxiety in specific situations are still lacking. To get high quality evidence of effectiveness of AT on anxiety (disorders), more robust studies are needed.

Besides anxiety symptoms, the effectiveness of AT on aspects of self-regulation like emotion regulation, cognitive regulation and stress regulation should be further studied as well. By evaluating the changes that may occur in the different areas of self-regulation, better hypotheses can be generated with respect to the working mechanisms of AT in the treatment of anxiety.

A key point for AT researchers in developing, executing and reporting on RCTs, is the issue of risk of bias. It is recommended to address more specifically how RoB was minimalized in the design and execution of the study. This can lower the RoB and therefor enhance the quality of the evidence, as judged by reviewers. One of the scientific challenges here is how to assess performance bias in AT reviews. Since blinding of therapists and patients in AT is impossible, and if performance bias is only considered by ‘lack of blinding of patients and personnel’, every trial on art therapy will have a high risk on performance bias, making the overall RoB high. This implies that high or even medium quality of evidence can never be reached for this intervention, even when all other aspects of the study are of high quality. Behavioral interventions, like psychotherapy and other complex interventions, face the same challenge. In 2017, Munder & Barth [ 48 ] published considerations on how to use the Cochrane's risk of bias tool in psychotherapy outcome research. We fully support the recommendations of Grant and colleagues [ 73 ] and would like to emphasize that tools for assessing risk of bias and quality of evidence need to be tailored to art therapy and (other) complex interventions where blinding is not possible.

The effectiveness of AT on reducing anxiety symptoms severity has hardly been studied in RCTs and nRCTs. There is low-quality to very low-quality evidence of effectiveness of AT for pre-exam anxiety in undergraduate students. AT may also be effective in reducing pre-release anxiety in prisoners.

The included RCTs demonstrate a wide variety in AT characteristics (AT types, numbers and duration of sessions). The described or hypothesized working mechanisms of art making are: induction of relaxation; working on emotion regulation by creating the safe condition for conscious expression and exploration of difficult emotions, memories and trauma; and working on cognitive regulation by using the art process to open up possibilities to investigate and (positively) change (unconscious) cognitions, beliefs and thoughts.

High quality trials studying effectiveness on anxiety and mediating working mechanisms of AT are currently lacking for all anxiety disorders and for people with anxiety in specific situations.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. prisma checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.s001

S1 File. Full list of search terms and databases.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.s002

S1 Table. Data extraction form.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.s003

S2 Table. Excluded studies with reasons for exclusion.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.s004

S3 Table. Background characteristics of the included studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716.s005

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. J.W. Schoones, information specialist and collection advisor of the Warlaeus Library of Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), for assisting in the searches.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 21. Nederland FeG. GZ Vaktherapeut. Beroepscompetentieprofiel. 2012.

- 22. Balkom ALJM van VIv, Emmelkamp PMG, Bockting CLH, Spijker J, Hermens MLM, Meeuwissen JAC. Multidisciplinary Guideline Anxiety Disorders (Third revision). Guideline for diagnostics and treatement of adult patients with an anxiety disorder. [Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Angststoornissen (Derde revisie). Richtlijn voor de diagnostiek, behandeling en begeleiding van volwassen patiënten met een angststoornis]. Utrecht: Trimbos Institute; 2013.

- 23. Malchiodi CA. Handbook of art therapy. Malchiodi CA, editor: New York, NY etc.: The Guilford Press; 2003.

- 24. Schweizer C, de Bruyn J, Haeyen S, Henskens B, Visser H, Rutten-Saris M. Art Therapy. Handbook Art therapy. [Beeldende therapie. Handboek beeldende therapie]. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2009. p. 25–77.

- 26. Haeyen S. Panel discussion for experienced arts therapist about arts therapies in the treatment of personality disorders. Internal document on behalf of the development of the National multi-disciplinary guideline for the treatment of personalities disorders. Utrecht: Trimbos Institute; 2005.

- 28. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: Oxford University Press; 2004 2004/04.

- 41. McGrath C. Music performance anxiety therapies: A review of the literature. In: Taylor S, editor.: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2012.

- 42. Higgins JPT GSe. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011].: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011; 2011 [Available from: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ .

- 46. Frances A, American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on D-I. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed., text revision. ed. Frances A, American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on D-I, editors: Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- 51. Asawa P. Reducing anxiety to technology: Utilizing expressive experiential interventions. In: Adams JD, editor.: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2003.

- 78. Cascone S. Experts Warn Adult Coloring Books are not Art Therapy https://news.artnet.com/art-world/experts-warn-adult-coloring-books-not-art-therapy-3235062015 [Available from: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/experts-warn-adult-coloring-books-not-art-therapy-323506 .

- 81. Csikszentimihalyi M. Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: HarperCollins; 1997.

- 82. Naumburg M. Dynamically oriented art therapy: its principles and practices. Illustrated with three case studies. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1966.

- 83. McNeilly G, Case C, Killick K, Schaverien J, Gilroy A. Changing Shape of Art Therapy: New Developments in Theory and Practice: London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2011.

- 85. Huijbregts SCJ. The role of stress in self-regulation and psychopathology [De rol van stress bij zelfregulatie en psychopathologie]. In: Swaab H, Bouma A., Hendrinksen J. & König C. (red) editor. Klinische kinderneuropsychologie. Amsterdam: Boom; 2015.

Advertisement

Review: systematic review of effectiveness of art psychotherapy in children with mental health disorders

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2021

- Volume 191 , pages 1369–1383, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Irene Braito ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3695-6464 1 , 2 ,

- Tara Rudd 3 ,

- Dicle Buyuktaskin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4679-3846 1 , 4 ,

- Mohammad Ahmed 1 ,

- Caoimhe Glancy 1 &

- Aisling Mulligan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7708-1177 3 , 5

14k Accesses

17 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Art therapy and art psychotherapy are often offered in Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHS). We aimed to review the evidence regarding art therapy and art psychotherapy in children attending mental health services. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO (CINHAL®Complete) following PRISMA guidelines, using the search terms (“creative therapy” OR “art therapy”) AND (child* OR adolescent OR teen*). We excluded review articles, articles which included adults, articles which were not written in English and articles without outcome measures. We identified 17 articles which are included in our review synthesis. We described these in two groups—ten articles regarding the treatment of children with a psychiatric diagnosis and seven regarding the treatment of children with psychiatric symptoms, but no formal diagnosis. The studies varied in terms of the type of art therapy/psychotherapy delivered, underlying conditions and outcome measures. Many were case studies/case series or small quasi-experimental studies; there were few randomised controlled trials and no replication studies. However, there was some evidence that art therapy or art psychotherapy may benefit children who have experienced trauma or who have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. There is extensive literature regarding art therapy/psychotherapy in children but limited empirical papers regarding its use in children attending mental health services. There is some evidence that art therapy or art psychotherapy may benefit children who have experienced trauma. Further research is required, and it may be beneficial if studies could be replicated in different locations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Art Therapy Interventions for Syrian Child and Adolescent Refugees: Enhancing Mental Well-being and Resilience

Art and evidence: balancing the discussion on arts- and evidence- based practices with traumatized children.

Art Therapy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) often offer art therapy, as well as many other therapeutic approaches; we wished to review the literature regarding art therapy in CAMHS. Previous systematic reviews of art therapy were not specifically focused on the effectiveness in children [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] or were focused on the use of art therapy in children with physical conditions rather than with mental health conditions [ 6 ]. The use of art or doodling as a communication tool in CAMHS is long established—Donald Winnicott famously used “the Squiggle Game” to break boundaries between a patient and professional to narrate a story through a simple squiggle [ 7 ]. Art is particularly useful to build a rapport with a child who presents with an issue that is too difficult to verbalise or if the child does not have words to express a difficulty. The term art therapy was coined by the artist Adrian Hill in 1942 following admission to a sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis, where artwork eased his suffering. “Art psychotherapy” expands on this concept by incorporating psychoanalytic processes, seeking to access the unconscious. Jung influenced the development of art psychotherapy as a means to access the unconscious and stated that “by painting himself he gives shape to himself” [ 8 ]. Art psychotherapy often focuses on externalising the problem, reflecting on it and analysing it which may then give way to seeing a resolution.

The UK Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health 2013 recommends that psychotherapists and creative therapists are part of the CAMHS teams [ 9 ]. There is a specific UK recommendation that art therapy may be used in the treatment of children and young people recovering from psychosis, particularly those with negative symptoms [ 10 ], but no similar recommendation in the Irish HSE National Clinical Programme for Early Intervention in Psychosis [ 11 ]. There is less clarity about the use of art therapy in the treatment of depression in young people—arts therapies were previously recommended [ 12 ], but more recent NICE guidelines appear to have dropped this advice, though the recommendation for psychodynamic psychotherapy has remained [ 13 ]. Art therapy is often offered to treat traumatised children, but we note that current NICE guidelines on the management of PTSD do not include a recommendation for art therapy [ 14 ]. The Irish document “Vision for Change” did not include a recommendation regarding art psychotherapy or creative therapies [ 15 ]. Similarly, the document “Sharing the Vision” does not make any recommendation regarding creative or art therapies, though it recommends psychotherapy for adults and recommends arts activities as part of social prescribing for adults [ 16 ]. Meanwhile, it is not uncommon for there to be an art therapist in CAMHS inpatient units, working with those with the highest mental healthcare needs. We wished to find out more about the evidence for, or indeed against, the use of art therapy in CAMHS. We performed a systematic review which aimed to clarify if art psychotherapy is effective for use in children with mental health disorders. This review aimed to address the following questions: (1) Is art therapy/psychotherapy an effective treatment for children with mental health disorders? (2) What are the various methods of art therapy or art psychotherapy which have been used to treat children with mental health disorders and how do they differ in terms of (i) setting and duration, (ii) procedure of the sessions, and (iii) art activities details?

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement for systematic reviews was followed. Searches and analysis were conducted between September 2016 and April 2020 using the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science and EBSCO (CINHAL®Complete). The following “medical subject terms” were utilized for searches: (“creative therapy” OR “art therapy”) AND (child* OR adolescent OR teen*). Review publications were excluded. Studies in the English language meeting the following inclusion criteria were selected: (i) use of art therapy/art psychotherapy, (ii) psychiatric disorder/diagnosis and/or mood disturbances and/or psychological symptoms, (iii) human participants aged 0–17 years inclusive. Articles investigating the efficiency of art therapy in children with medical conditions were included only if the measured outcome related to psychological well-being/symptoms. Exclusion criteria included: (i) application of therapies which do not involve art activities, (ii) application of a combination of therapies without individual results for art therapy, (iii) not clinical studies (review, meta-analysis, reports, others), (iv) studies which focused on the artwork itself/art therapy procedure and did not measure and publish any clinical outcomes, (v) absence of any pre psychiatric symptoms or comorbidity in the participant sample prior to art intervention. All articles were screened for inclusion by the authors (MA, TR, IB, AM, DB), unblinded to manuscript authorship.

Data extraction

The authors (IB, TR, AM, MA, DB) extracted all data independently (unblinded). Data were extracted and recorded in three tables with specific information from each study on (i) the study details, (ii) art therapy details and outcome measures and (iii) art therapy results. The following specific study details were extracted: author/journal, country, year of publication, study type (i.e. study design), study aims, study setting, participant details (number, age and gender), disease/disorder studied and inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria of the study. The following details were extracted regarding the art therapy provided and outcome measures : type of art therapy provided (individual or group therapy), the art therapy procedure and/or techniques used, the art therapy setting, therapy duration (including frequency and duration of each art therapy session), the type of outcome measure used, the investigated domains, the time points (for outcome measures) and the presence or absence of pre-/post-test statistical analysis. Finally, we extracted specific information on the art therapy results , including therapy group results, control group results, the number and percentage of who completed therapy, whether or not a pre-/post-test statistical difference was found and the general outcome of each study. Following the extraction of all data, studies included were divided into two groups: (1) children with psychiatric disorder diagnosis and (2) children with psychiatric symptoms. Finally, the QUADAS-2 tool was used to assess the risk of bias for each study, and a summary of the risk of bias for all data was calculated [ 17 ]. The QUADAS-2 is designed to assess and record selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and any other bias [ 17 ].

Study inclusion and assessment

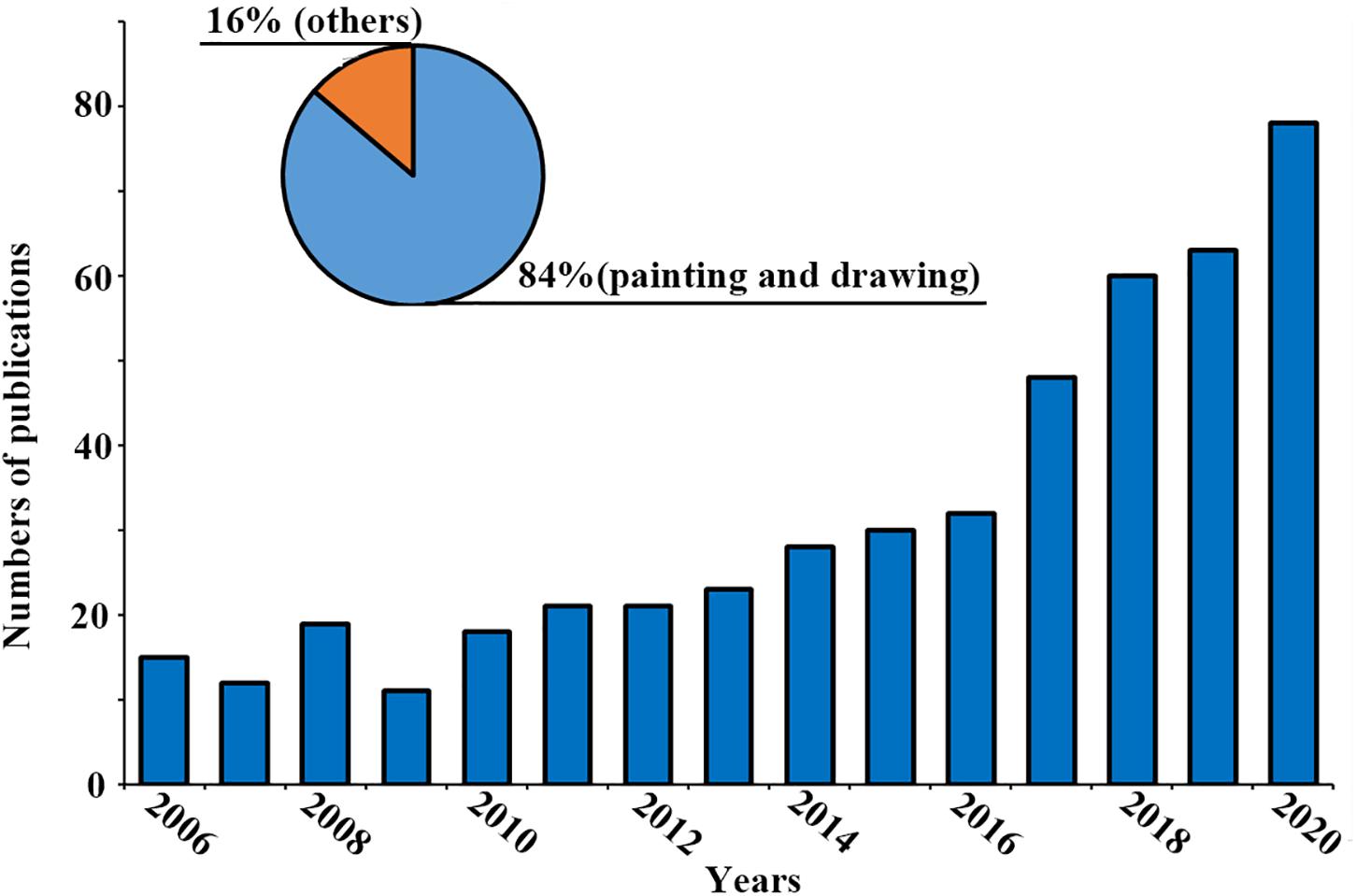

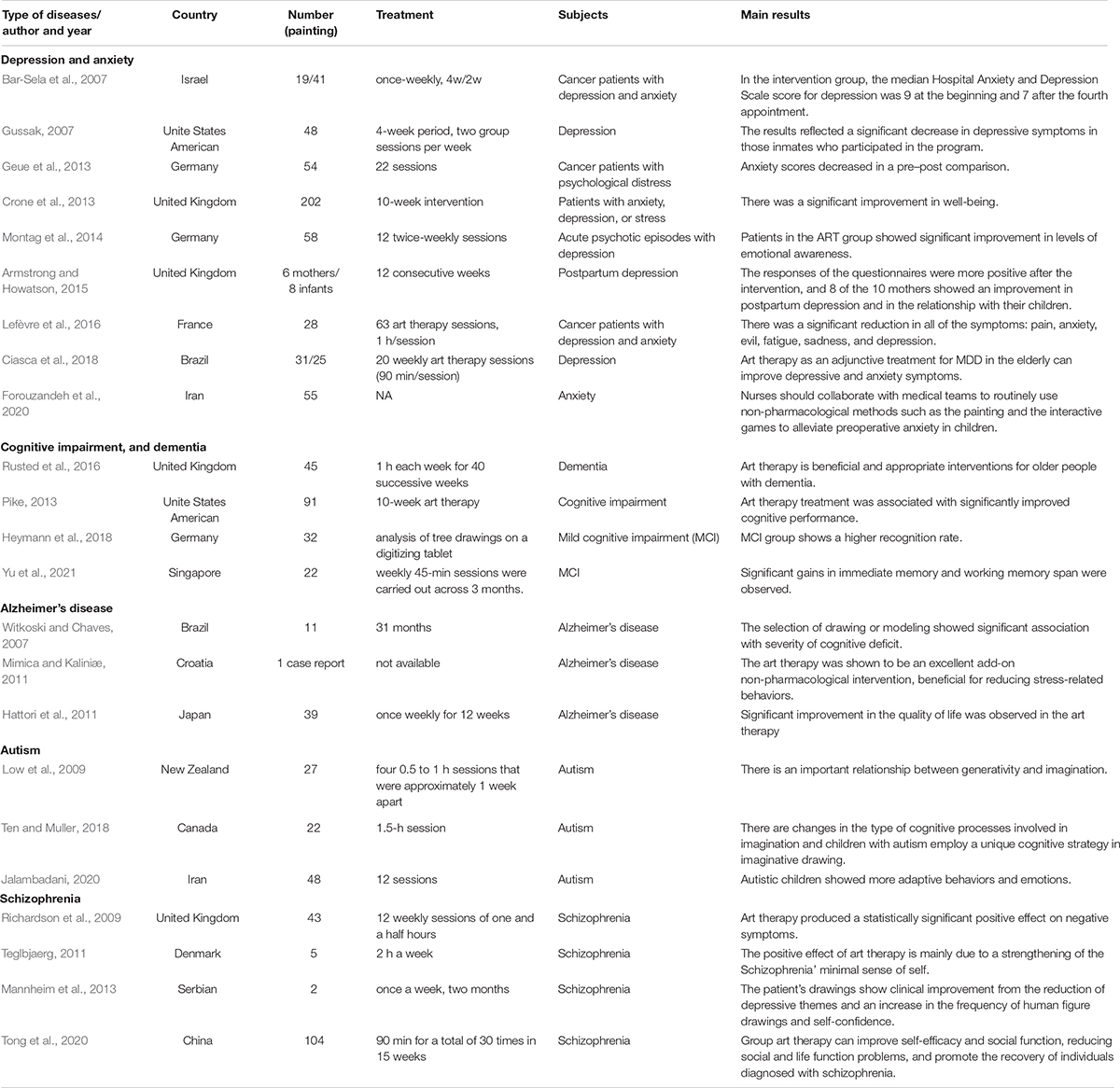

A total of 1273 articles were initially identified (Fig. 1 ). After repeats and duplicates were removed, 1186 possible articles were identified and screened for inclusion/exclusion according to the title and abstract, which resulted in 1000 articles being excluded. The remaining 186 full articles were retrieved and full text considered. Following review of the full text, 70 articles were selected and further analysed. Fifty-three of them did not meet our criteria for review. Reasons for exclusion were grouped into four main categories: (1) not art therapy [ n = 2]; (2) not mental health [ n = 5]; (3) no outcome measured [ n = 18]; (4) other reasons (i.e. descriptive texts, full article not available) [ n = 28]. In conclusion, there were 17 articles remaining that met the full inclusion criteria, and further descriptive analysis was performed on these 17 studies. All the considered articles were produced in the twenty-first century, between 2001 and 2020, most in the USA (60%), followed by Canada (30%) and Italy (10%). The characteristics of studies included in our final synthesis are reported in Tables 1 and 2 .

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Participant characteristics

Participants in the 17 studies ranged from 2 to 17 years old inclusive. In ten articles, children with an established psychiatric diagnosis were included (Group 1, see Table 1 ). The type of psychiatric disorders as (i) PTSD, (ii) mood disorders (bipolar affective disorder, depressive disorders, anxiety disorder), (iii) self-harm behaviour, (iv) attachment disorder, (v) personality disorder and (vi) adjustment disorder. In seven articles, children with psychiatric symptoms were enrolled, usually referred by practitioners and school counsellors (Group 2, see Table 2 ). Participants had a wide variety of conditions including (i) symptoms of depression, anxiety, low mood, dysthymic features; (ii) attention and concentration disorder symptoms; (iii) socialisation problems and (iv) self-concept and self-image difficulties. Some children had medical conditions such as leukaemia requiring painful procedures, or glaucoma, cancer, seizures, acute surgery; others had experienced adversity such as parental divorce, physical, emotional and/or sexual abuse or had developed dangerous and promiscuous social habits (drugs, prostitution and gang involvement).

Study design: children with an established psychiatric diagnosis (Table 1 )

A summary of the ten studies on art therapy in children with a psychiatric diagnosis can be seen in Table 1 , with further information about each study. There are just two randomised controlled in this category, both treating PTSD in children [ 18 , 19 ]. Chapman et al. [ 18 ] provided individual art therapy to young children who had experienced trauma and assessed symptom response using the PTSD-I assessment of symptoms 1 week after injury and 1 month after hospital admission [ 18 ]. Their study included 85 children; 31 children received individual art therapy, 27 children received treatment as usual and 27 children did not meet criteria for PTSD on the initial PTSD-I assessment [ 18 ]. The art therapy group had a reduction in acute stress symptoms, but there was no significant difference in PTSD scores [ 18 ]. The second randomised controlled trial provided trauma-focused group art therapy in an inpatient setting and showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms in adolescents who attended art therapy in comparison to a control group who attended arts-and-crafts. However, this study had a high drop-out rate, with 142 patients referred to the study and just 29 patients who completed the study [ 19 ].

The remaining studies regarding art therapy or art psychotherapy in children with psychiatric disorders are case studies, case series or quasi experimental studies, most with less than five participants. All these studies reported positive effects of art therapy; we did not find any published negative studies. We can summarise that the studies differed greatly in the type of therapy delivered, in the setting (group or individual therapy) and in the types of disorders treated (Table 1 ).

Forms of art therapy intervention and assessment (Table 1 )

The various modalities and duration of art therapy described in the ten studies with children with psychiatric diagnoses are summarised in Table 1 . The treatment of PTSD was described in two studies, but each described a different art therapy protocol, and the studies varied in terms of setting and duration [ 18 , 19 ]. The Trauma Focused Art Therapy (TF-ART) study described 16 weekly in-patient group sessions [ 19 ], whereas the Chapman Art Therapy Treatment Intervention (CATTI) is a short-term individual therapy, lasting 1 h at the bedside of hospital inpatients [ 18 ]. Despite the differences, the methods have some common aspects. Both therapy methods focused on helping the individual express a narrative of his/her life story, supporting the individual to reflect on trauma-related experiences and to describe coping responses. Relaxation techniques were used, such as kinaesthetic activities [ 18 ] and “feelings check-ins” [ 19 ]. In the TF-ART protocol, each participant completed at least 13 collages or drawings and compiled in a hand-made book to describe his/her “life story” [ 19 ]. The use of art therapy in a traumatised child has also been described in a single case study [ 20 ].

Group art therapy has been described in the treatment of adolescent personality disorder, in an intervention where adolescents met weekly in two separate periods of 18 sessions over 6 months, with each session lasting 90 min, facilitated by a psychotherapist [ 21 ]. Sessions consisted of a short group conversation regarding events/issues during the previous week followed by a brief relaxing activity (e.g. listening to music), a period of art-making and an opportunity to explain their work, guided by the psychotherapist.

A long course of art psychotherapy over 3 years with a vulnerable female adolescent who presented with self-harm and later disclosed being a victim of a sexual assault has been described [ 22 ]. The young person described an “enemy” inside her which she had overcome in her testimony to her improvement, which was included in the published case study [ 22 ]. The approach of “art as therapy” has been described with children with bipolar disorder and other potential comorbidities, such as Asperger syndrome and attention deficit disorder, using the “naming the enemy” and “naming the friend” approaches [ 23 ].

The concept of the “transitional object”—a coping device for periods of separation in the mother–child dyad during infancy—has been considered in art therapy [ 24 ]. It was proposed that “transitional objects” could be used as bridging objects between a scary reality and the weak inner-self. Children brought their transitional objects to therapy sessions, and the therapy process aimed to detach the participant from his/her transitional object, giving him/her the strength to face life situations with his/her own capabilities [ 24 ].

Two studies of art therapy in children with adjustment disorders were included in our systematic review [ 25 , 26 ]. Children attended two or three video-recorded sessions and were encouraged to use art materials to explore daily life events. The child and therapist then watched the video-recorded session and participated in a semi-structured interview that employed video-stimulated recall. The therapy aimed to transport the participant to a comfortable imaginary world, giving the child the possibility to create powerful, strong characters in his/her story, thus enhancing the ability to cope with life’s challenges [ 25 , 26 ].

Outcome measures and statistical analysis (Table 1 )

Three articles on psychiatric disorders evaluated potential changes in outcome using an objective measure [ 18 , 19 , 22 ]. Two studies used the “The University of California at Los Angeles Children’s PTSD Index” (UCLA PTSD-I), which is a 20-item self-report tool [ 18 , 19 ]. Statistical differences were evaluated by calculating the mean percentage change [ 18 ] and the ANOVA [ 19 ]. The 12-item “MacKenzie’s Group Climate Questionnaire” was used to measure the outcome of group art therapy in adolescents with personality disorder, and a significant reduction in conflict in the group was found [ 21 ]. However, the sample size was small, and there was no control group [ 21 ]. Many studies did not use highly recognised measures of outcome but relied instead on a comprehensive description of outcome or change after art therapy/psychotherapy, in case studies or case series [ 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ].

Study design: children with psychiatric symptoms (Table 2 )

We included seven studies in our review synthesis where art therapy or art psychotherapy was used as an intervention for psychiatric symptoms—many of these studies occurred in paediatric hospitals, where children were being treated for other conditions. Two of these studies were non-randomised controlled trials, one of which was waitlist controlled [ 28 , 29 ], and the other five were quasi-experimental studies [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Forms of intervention and assessment (Table 2 )

Three articles described art therapy in paediatric hospital patients but varied in terms of therapy and underlying condition [ 28 , 29 , 33 ]. The effectiveness of art therapy on self-esteem and symptoms of depression in children with glaucoma has been investigated; a number of sensory-stimulating art materials were introduced during six individual 1-h sessions [ 33 ]. Short-term or single individual art therapy sessions have also been used in hospital aiming to improve quality of life [ 28 , 29 ]. Art therapy has been provided to children with leukaemia; the children transformed unused socks into puppets called “healing sock creatures” [ 29 ]. Short-term art therapy prior to painful procedures, such as lumbar puncture or bone marrow aspiration, has also been described, using “visual imagination” and “medical play” with age-appropriate explanations about the procedure, with a cloth doll and medical instruments [ 28 ].

The remaining articles described the provision of art therapy to vulnerable patients, where the therapy aimed to increase self-confidence or address worries. Two studies focused on female self-esteem and self-concept, both using group activities [ 31 , 32 ]. Hartz and Thick [ 32 ] compared two different art therapy protocols: art psychotherapy, which employed a brief psychoeducational presentation and encouraged abstraction, symbolization and verbalization and an art as therapy approach, which highlighted design potentials, technique and the creative problem-solving process, trying to evoke artistic experimentation and accomplishment rather than different strengths and aspects of personality [ 32 ]. Participants completed a known questionnaire about self-esteem as well as a study-specific questionnaire.

Coholic and Eys [ 34 ] described the use of a 12-week arts-based mindfulness group programme with vulnerable children referred by mental health or child welfare services, with a combination of group work and individual sessions [ 34 ]. Children were given tasks which included the “thought jar” (filling an empty glass jar with water and various-shaped and coloured beads representing thoughts and feelings), the “me as a tree” activity, during which the participant drew him/herself as a tree, enabling the participant to introduce him/herself, the “emotion listen and draw” activity which provided the opportunity to draw/paint feelings while listening to five different songs and the “bad day better” activity which involved painting what a “bad day” looked like, and then to decorate it to turn it into a “good day”. The research included quantitative analysis and qualitative assessment using self-report Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale and the Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents [ 37 , 38 ].

Kearns [ 30 ] described a single case study of art therapy with a child with a sensory integration difficulty, comparing teacher-reported behaviour patterns after art therapy sessions using kinaesthetic stimulation and visual stimulation with behaviour after 12 control sessions of non-art therapy; a greater improvement was reported with art therapy [ 30 ].

Outcome measures and statistical analysis (Table 2 )

Most of the studies on art therapy in children with psychiatric symptoms (but not confirmed disorders) used widely accepted outcome measures [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ] (Table 2 ), such as self-report measurements including the 27-item symptom-orientated Children’s Depression Inventory or the Tennessee Self Concept Scale: Short Form [ 33 , 35 , 36 ]. The 60-item Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (2nd edition) and the Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents (RSCA) were used in a study on vulnerable children [ 34 , 37 , 38 ]. The Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale is a widely used self-report measure of psychological health and self-concept in children and teens and consists of three global self-report scales presented in a 5-point Likert-type scale: sense of mastery (20 items), sense of relatedness (24 items) and emotional reactivity (20 items) [ 37 ]. A modified version of the Daley and Lecroy’s Go Grrrls Questionnaire was administered at group intake and follow-up, to rank various self-concept items including body image and self-esteem along a four-point ordinal scale in group therapy with young females [ 31 , 39 ].

Some researchers created their own outcome measures [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 33 ]. One study group created a mood questionnaire for young children—this was administered by a research assistant to patients before and after each therapy session, in their small wait-list controlled study [ 29 ]. Another group evaluated classroom performance using an observational system rated by the teacher for each 30-min block of time every day during the study [ 30 ]. The classroom study also used the “person picking an apple from a tree” (PPAT) drawing task—this was the only measurement tool in the studies we reviewed which assessed the features of the artworks themselves [ 30 , 40 ]. Pre- and post-test drawings were evaluated for evidence of changes in various qualities over the course of the research period [ 30 ].

Hartz and Thick [ 32 ] used both the 45-items Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA) [ 41 ] which is widely used and considered reliable, as well as the Hartz Art Therapy Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Hartz AT-SEQ) [ 32 ], which is a 20-question post-treatment questionnaire designed by the author, to understand how specific aspects of art therapy treatment affect self-esteem in a quasi-experimental study with group art therapy. Four of the seven articles performed statistical analysis of the data collected, using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [ 31 ], Fisher’s t [ 32 ], MANOVA [ 34 ], and two-tailed Student’s t test [ 29 ].

Assessment of bias

The QUADAS-2 assessment of bias for each study included in our systematic review synthesis can be seen in Table 3 , with a summary of the results of the QUADAS-2 assessment for all included studies in our review in Table 4 . Studies marked in green had a low risk of bias; those marked in red had a high risk of bias while those in yellow had an unclear risk of bias. Just two studies were found to have a low risk of bias [ 19 , 29 ].

We found extensive literature regarding the use of art therapy in children with mental health difficulties ( N = 1273), with a large number of descriptive qualitative studies and cases studies, but a limited number of quantitative studies which we could include in our review synthesis ( N = 17). The predominance of descriptive studies is not surprising considering that the field of art therapy and art psychotherapy has developed from the descriptive writings of Freud, Jung, Winnicott and others, and for many years, academic psychotherapy focused on detailed case descriptions rather than quantitative outcome studies. The numerous descriptive and qualitative publications generally described positive changes in participants undergoing art therapy, which may represent publication bias. Our aim was however to describe the quantitative evidence regarding the use of art therapy or art psychotherapy in children and adolescents with mental health difficulties, and we found a limited number of studies to include in our review synthesis. There were just two randomised controlled trials, no replication studies and insufficient information to allow for a meta-analysis. However, the articles in our review synthesis suggested that art therapy may have a positive outcome in various groups of patients, especially if the therapy lasts at least 8 weeks.

There is some evidence from controlled trials to support the use of art therapy in children who have experienced trauma [ 18 , 19 ]. It should be noted that art therapy or art psychotherapy was delivered as individual sessions in most of the studies in our review, especially for children with a psychiatric diagnosis. A group approach to art therapy was used in some studies with vulnerable children such as children in need, female adolescents with self-esteem issues and female offenders [ 22 , 31 , 34 ]. However, the studies on group art therapy or psychotherapy are quasi-experimental studies of limited size, and it would be useful if larger, more robust studies such as randomised controlled trials could study the efficacy of group art therapy or group art psychotherapy.

Many of the studies included in our review synthesis ranked low in the Cochrane Risk of Bias criteria, with a high risk of bias. Our review synthesis highlights the heterogeneity of the studies—various methods of individual or group art therapy were delivered, with some studies delivering psychoanalytic-type interventions while others delivered interventions resembling cognitive behaviour therapy, delivered via art. The literature also showed a general lack of standardisation with regard to the duration of art therapy and outcome measures used. Despite this, the authors of many of the studies described common themes and hypothesised about the value of art therapy or art psychotherapy in improving self-esteem, communication and integration. The interventions often encouraged the child to re-enact or to process trauma, and the authors described improved integration, and therapeutic change or transformation of the young person. It appears that there were varied interventions in the studies in the review synthesis but that many studies had theoretical similarities.

Strengths and limitations