- Help Animals

- Investigations

- Animal Rights Issues

- Students Opposing Speciesism (SOS)

- Join the Action Team

- Monthly Giving

- Your Legacy For Animals

- PETA Vanguard Society

- ‘In Honor of’ and Memorial Gifts

- Membership Services

- More Ways to Support PETA

- Report Cruelty to Animals

Urgent Alerts

- Our Campaigns

- Action Team

- Activist Guide

- Get Active Online

- Leaflets & Stickers

- Adoptable Animals

- Rescue Stories

- Recent Investigations

- Investigations & Rescue Fund

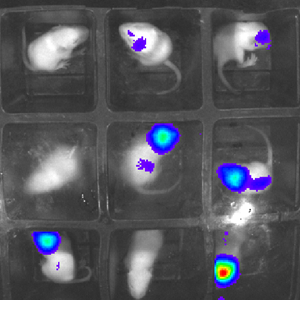

- Animals Used for Experimentation

- Entertainment

- Companion Animals

- Personal Care & Fashion

- Food & Health

- Humane Home

- Animal Companions

- Cruelty-Free Database

- PETA Shopping Guide

- PETA Approved Vegan

- PETA Presents

- Work at PETA

- PETA Global

- Vanguard Society

- More Ways to Support

- Gifts in Wills

The Silver Spring Monkeys: The Case That Launched PETA

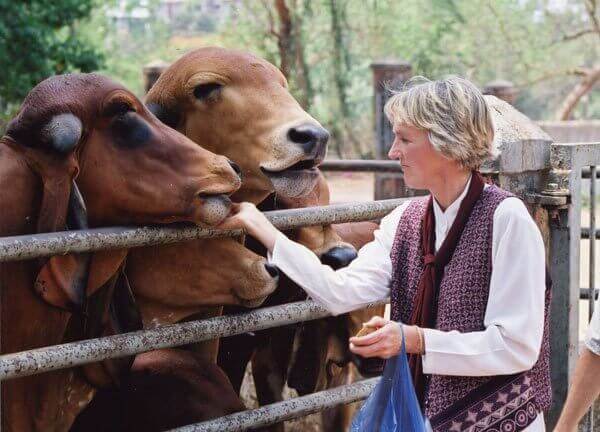

In the summer of 1981, PETA’s founder, Ingrid Newkirk , leafed through the pages of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s list of laboratories, picked the closest one, and asked her colleague, Alex, to see if he could get inside. He did and began working as a volunteer at the Institute for Behavioral Research (IBR). IBR was a federally funded laboratory in Silver Spring, Maryland, now closed down for reasons that will soon become apparent. It was run out of a warehouse by psychologist and animal experimenter Edward Taub, a man with no medical training. There, we found 17 monkeys living in tiny rusty wire cages caked with years of accumulated feces in a dungeon-like room. There was no veterinarian to tend to their serious wounds, and they had a lot of them.

Taub, who also had no veterinary training, nevertheless subjected the monkeys to surgeries in which he severed their spinal nerves, rendering one or more of their limbs useless. By means of electric shock, food deprivation, and other cruel methods, he forced them to try to regain the use of their impaired limbs to pick up raisins from a tray—or else go without food. In one experiment, monkeys were shut inside a converted refrigerator and repeatedly electro-shocked until they finally used their disabled arm, if they could. The inside of the refrigerator was covered with blood. In another experiment, monkeys were strapped into a crude restraint chair—their waist, ankles, wrists, and neck held in place with packing tape—and pliers were latched as tightly as possible onto their skin, including on their testicles.

The trauma of the monkeys’ imprisonment and treatment was so severe that many of them had ripped at their own flesh, and they had lost many of their fingers from catching them in the rusted, jagged cage bars. Workers often neglected to feed the monkeys, and the animals would desperately pick through the stinking urine and fecal waste in trays beneath their cages to find something to eat.

PETA gathered meticulous log notes detailing what was happening inside IBR and secretly photographed the crippled monkeys and their horrendous living conditions. Then, after lining up expert witnesses and showing them around the laboratory at night, PETA took the evidence to the police—and an intense, decade-long battle for custody of the monkeys ensued.

This groundbreaking investigation led to the nation’s first arrest and criminal conviction of an animal experimenter for cruelty to animals, the first confiscation of abused animals from a laboratory, and the first U.S. Supreme Court victory for animals used in experiments. It even led to landmark additions to the Animal Welfare Act—and unrelenting public scrutiny of the abuse that animals endure in experimentation . And IBR closed its doors.

PETA has scored many victories for animals in laboratories since the landmark Silver Spring monkeys case, but tragically, experiments like this still go on. You can help by asking your congressional representatives to divert public money from cruel animal experiments into promising, lifesaving, and relevant clinical and non-animal research.

What PETA found on 12 farms exposes how the ASPCA, The Humane Society of the United States, and another “animal welfare” group are endorsing massive animal suffering!

Urge Coach to end its greenwashing and switch to vegan leather.

Urge the Namibian government to reconsider its cruel plans and put a stop to the proposed slaughter.

Urge these Pigeon Forge hotels to reconsider their relationship with Parrot Mountain and to avoid exhibiting parrots or any other wild animals.

Urge Groupon’s CEO to stop selling tickets to SeaWorld.

By submitting this form, you’re acknowledging that you have read and agree to our privacy policy and agree to receive e-mails from us.

“Almost all of us grew up eating meat, wearing leather, and going to circuses and zoos. We never considered the impact of these actions on the animals involved. For whatever reason, you are now asking the question: Why should animals have rights? ”

— Ingrid E. Newkirk, PETA President and co-author of Animalkind

Text CRAZY to 73822 to take action for chimpanzees suffering in human homes & roadside zoos! Then watch Chimp Crazy, HBO’s new docuseries to learn more.

Terms for automated texts/calls from PETA: http://peta.vg/txt . Text STOP to end, HELP for more info. Msg/data rates may apply. U.S. only.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

EVs fight warming but are costly. Why aren’t we driving $10,000 Chinese imports?

Toll of QAnon on families of followers

The urgent message coming from boys

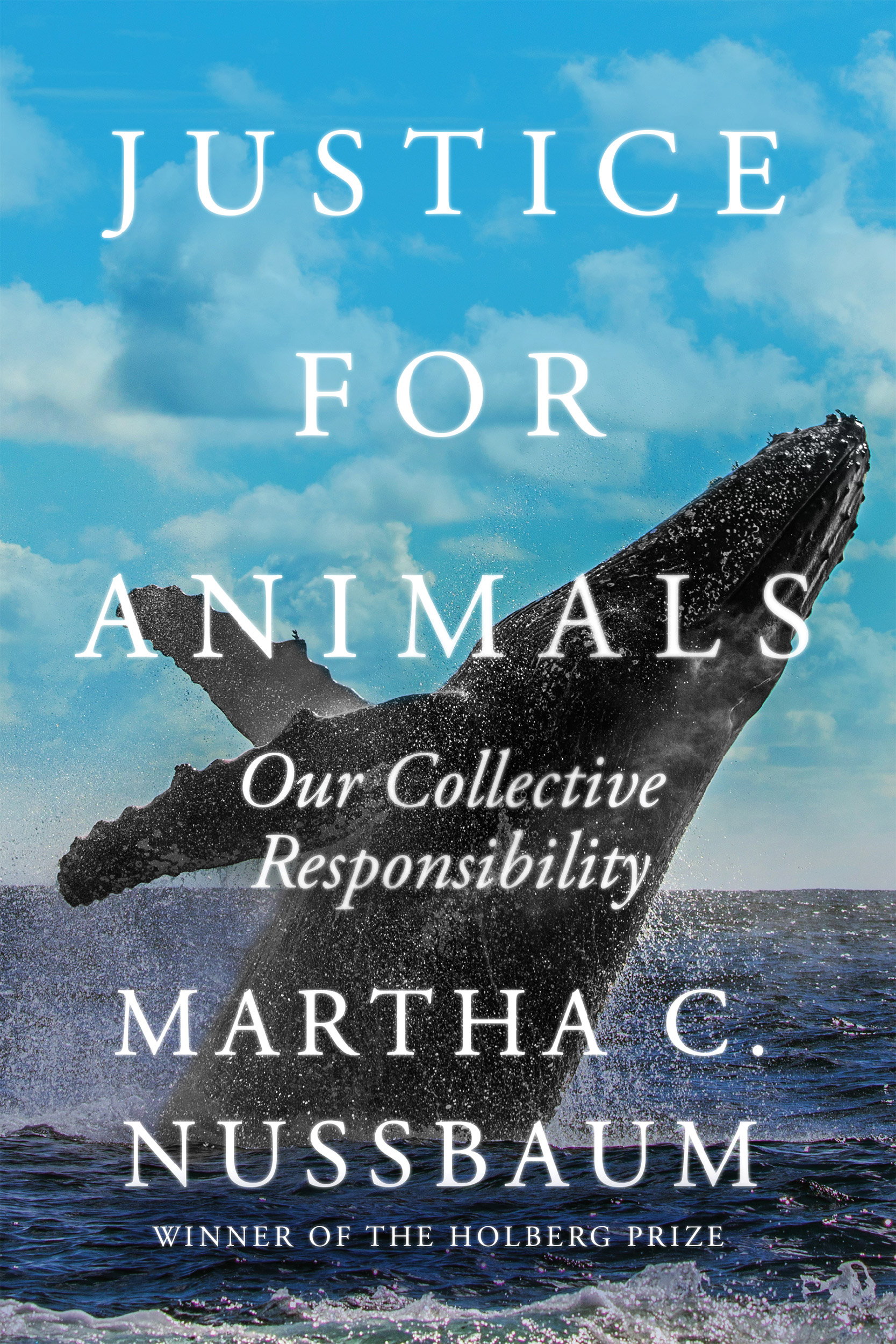

They can think, feel pain, love. isn’t it time animals had rights.

Martha Nussbaum lays out ethical, legal case in new book

Martha Nussbaum

Excerpted from “Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility” by Martha C. Nussbaum, M.A. ’71, Ph.D. ’75

Animals are in trouble all over the world. Our world is dominated by humans everywhere: on land, in the seas, and in the air. No non-human animal escapes human domination. Much of the time, that domination inflicts wrongful injury on animals: whether through the barbarous cruelties of the factory meat industry, through poaching and game hunting, through habitat destruction, through pollution of the air and the seas, or through neglect of the companion animals that people purport to love.

In a way, this problem is age-old. Both Western and non-Western philosophical traditions have deplored human cruelty to animals for around two millennia. The Hindu emperor Ashoka (c. 304–232 bce), a convert to Buddhism, wrote about his efforts to give up meat and to forgo all practices that harmed animals. In Greece the Platonist philosophers Plutarch (46–119 ce) and Porphyry (c. 234–305 ce) wrote detailed treatises deploring human cruelty to animals, describing their keen intelligence and their capacity for social life, and urging humans to change their diet and their way of life. But by and large these voices have fallen on deaf ears, even in the supposedly moral realm of the philosophers, and most humans have continued to treat most animals like objects, whose suffering does not matter — although they sometimes make an exception for companion animals. Meanwhile, countless animals have suffered cruelty, deprivation, and neglect.

Because the reach of human cruelty has expanded, so too has the involvement of virtually all people in it. Even people who do not consume meat produced by the factory farming industry are likely to have used single-use plastic items, to use fossil fuels mined beneath the ocean and polluting the air, to dwell in areas in which elephants and bears once roamed, or to live in high-rise buildings that spell death for migratory birds. The extent of our own implication in practices that harm animals should make every person with a conscience consider what we can all do to change this situation. Pinning guilt is less important than accepting the fact that humanity as a whole has a collective duty to face and solve these problems.

So far, I have not spoken of the extinction of animal species, because this is a book about loss and deprivation suffered by individual creatures, each of whom matters. Species as such do not suffer loss. However, extinction never takes place without massive suffering of individual creatures: the hunger of a polar bear, starving on an ice floe, unable to cross the sea to hunt; the sadness of an orphan elephant, deprived of care and community as the species dwindles rapidly; the mass extinctions of song-bird species as a result of unbreathable air, a horrible death. When human practices hound species toward extinction, member animals always suffer greatly and live squashed and thwarted lives. Besides, the species themselves matter for creating diverse ecosystems in which animals can live well.

Extinctions would take place even without human intervention. Even in such cases we might have reasons to intervene to stop them, because of the importance of biodiversity. But scientists agree that today’s extinctions are between one thousand and ten thousand times higher than the natural extinction rate. (Our uncertainty is huge, because we are very ignorant of how many species there actually are, particularly where fish and insects are concerned.) Worldwide, approximately one-quarter of the world’s mammals and over 40 percent of amphibians are currently threatened with extinction. These include several species of bear, the Asian elephant (endangered), the African elephant (threatened), the tiger, six species of whale, the gray wolf, and so many more. All in all, more than 370 animal species are either endangered or threatened, using the criteria of the US Endangered Species Act, not including birds, and a separate list of similar length for birds. Asian songbirds are virtually extinct in the wild, on account of the lucrative trade in these luxury items. And many other species of birds have recently become extinct. Meanwhile, the international treaty called CITES that is supposed to protect birds (and many other creatures) is toothless and unenforced. The story of this book is not that story of mass extinction, but the sufferings of individual creatures that take place against this background of human indifference to biodiversity.

“The extent of our own implication in practices that harm animals should make every person with a conscience consider what we can all do to change this situation.”

There is a further reason why the ethical evasion of the past must end now. Today we know far more about animal lives than we did even 50 years ago. We know much too much for the glib excuses of the past to be offered without shame. Porphyry and Plutarch (and Aristotle before them) knew a lot about animal intelligence and sensitivity. But somehow humans find ways of “forgetting” what the science of the past has plainly revealed, and for many centuries most people, including most philosophers, thought animals were “brute beasts,” automata without a subjective sense of the world, without emotions, without society, and perhaps even without the feeling of pain.

Recent decades, however, have seen an explosion of high-level research covering all areas of the animal world. We now know more not only about animals long closely studied — primates and companion animals — but also about animals who are difficult to study — marine mammals, whales, fish, birds, reptiles, and cephalopods.

We know — not just by observation, but by carefully designed experimental work — that all vertebrates and many invertebrates feel pain subjectively, and have, more generally, a subjectively felt view of the world: the world looks like something to them. We know that all of these animals experience at least some emotions (fear being the most ubiquitous), and that many experience emotions like compassion and grief that involve more complex “takes” on a situation. We know that animals as different as dolphins and crows can solve complicated problems and learn to use tools to solve them. We know that animals have complex forms of social organization and social behavior. More recently, we have been learning that these social groups are not simply places where a rote inherited repertory is acted out, but places of complicated social learning. Species as different as whales, dogs, and many types of birds clearly transmit key parts of the species’ repertoire to their young socially, not just genetically.

What are the implications of this research for ethics? Huge, clearly. We can no longer draw the usual line between our own species and “the beasts,” a line meant to distinguish intelligence, emotion, and sentience from the dense life of a “brute beast.” Nor can we even draw a line between a group of animals we already recognize as sort of “like us” — apes, elephants, whales, dogs — and others who are supposed to be unintelligent. Intelligence takes multiple and fascinating forms in the real world, and birds, evolving by a very different path from humans, have converged on many similar abilities. Even an invertebrate such as the octopus has surprising capacities for intelligent perception: an octopus can recognize individual humans, and can solve complex problems, guiding one of its arms through a maze to obtain food using only its eyes. Once we recognize all this we can hardly be unchanged in our ethical thinking. To put a “brute beast” in a cage seems no more wrong than putting a rock in a terrarium. But that is not what we are doing. We are deforming the existence of intelligent and complexly sentient forms of life. Each of these animals strives for a flourishing life, and each has abilities, social and individual, that equip it to negotiate a decent life in a world that gives animals difficult challenges. What humans are doing is to thwart this striving — and this seems wrong.

But even though the time has come to recognize our ethical responsibility to the other animals, we have few intellectual tools to effect meaningful change. The third reason why we must confront what we are doing to animals now, today, is that we have built a world in which two of humanity’s best tools for progress, law and political theory, have, so far, no or little help to offer us. Law — both domestic and international — has quite a lot to say about the lives of companion animals, but very little to say about any other animals. Nor do animals in most nations have what lawyers call “standing”: that is, the status to bring a legal claim if they are wronged. Of course, animals cannot themselves bring a legal claim, but neither can most humans, including children, people with cognitive disabilities — and, to tell the truth, almost everybody, since people have little knowledge of the law. All of us need a lawyer to press our claims. But all the humans I have mentioned — including people with lifelong cognitive disabilities — count, and can bring a legal claim, assisted by an able advocate. The way we have designed the world’s legal systems, animals do not have this simple privilege. They do not count.

Law is built by humans using the theories they have. When those theories were racist, laws were racist. When theories of sex and gender excluded women, so too did law. And there is no denying that most political thought by humans the world over has been human-centered, excluding animals. Even the theories that purport to offer help in the struggle against abuse are deeply defective, built on an inadequate picture of animal lives and animal striving. As a philosopher and political theorist who is also deeply immersed in law and law teaching, I hope to change things with this book.

Copyright © 2022 by Martha Nussbaum. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Share this article

You might like.

Experts say tension between trade, green-tech policies hampers climate change advances; more targeted response needed

New book by Nieman Fellow explores pain, frustration in efforts to help loved ones break free of hold of conspiracy theorists

When we don’t listen, we all suffer, says psychologist whose new book is ‘Rebels with a Cause’

Billions worldwide deficient in essential micronutrients

Inadequate levels carry risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, blindness

You want to be boss. You probably won’t be good at it.

Study pinpoints two measures that predict effective managers

Weight-loss drug linked to fewer COVID deaths

Large-scale study finds Wegovy reduces risk of heart attack, stroke

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Oxford Journal of Legal Studies

- About University of Oxford Faculty of Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction: the need for legal animal rights theory, 2. can animals have legal rights, 3. do animals have (simple) legal rights, 4. should animals have (fundamental) legal rights, 5. conclusion.

- < Previous

Towards a Theory of Legal Animal Rights: Simple and Fundamental Rights

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Saskia Stucki, Towards a Theory of Legal Animal Rights: Simple and Fundamental Rights, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies , Volume 40, Issue 3, Autumn 2020, Pages 533–560, https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

With legal animal rights on the horizon, there is a need for a more systematic theorisation of animal rights as legal rights. This article addresses conceptual, doctrinal and normative issues relating to the nature and foundations of legal animal rights by examining three key questions: can, do and should animals have legal rights? It will show that animals are conceptually possible candidates for rights ascriptions. Moreover, certain ‘animal welfare rights’ could arguably be extracted from existing animal welfare laws, even though these are currently imperfect and weak legal rights at best. Finally, this article introduces the new conceptual vocabulary of simple and fundamental animal rights, in order to distinguish the weak legal rights that animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law from the kind of strong legal rights that animals ought to have as a matter of future law.

Legal animal rights are on the horizon, and there is a need for a legal theory of animal rights—that is, a theory of animal rights as legal rights. While there is a diverse body of moral and political theories of animal rights, 1 the nature and conceptual foundations of legal animal rights remain remarkably underexplored. As yet, only few and fragmented legal analyses of isolated aspects of animal rights exist. 2 Other than that, most legal writing in this field operates with a hazily assumed, rudimentary and undifferentiated conception of animal rights—one largely informed by extralegal notions of moral animal rights—which tends to obscure rather than illuminate the distinctive nature and features of legal animal rights. 3 A more systematic and nuanced theorisation of legal animal rights is, however, necessary and overdue for two reasons: first, a gradual turn to legal rights in animal rights discourse; and, secondly, the incipient emergence of legal animal rights.

First, while animal rights have originally been framed as moral rights, they are increasingly articulated as potential legal rights. That is, animals’ moral rights are asserted in an ‘ought to be legal rights’-sense (or ‘manifesto sense’) 4 that demands legal institutionalisation and refers to the corresponding legal rights which animals should ideally have. 5 A salient reason for transforming moral into legal animal rights is that purely moral rights (which exist prior to and independently of legal validation) do not provide animals with sufficient practical protection, whereas legally recognised rights would be reinforced by the law’s more stringent protection and enforcement mechanisms. 6 With a view to their (potential) juridification, it seems advisable to rethink and reconstruct animal rights as specifically legal rights, rather than simply importing moral animal rights into the legal domain. 7

Secondly, and adding urgency to the need for theorisation, legal animal rights are beginning to emerge from existing law. Recently, a few pioneering courts have embarked on a path of judicial creation of animal rights, arriving at them either through a rights-based interpretation of animal welfare legislation or a dynamic interpretation of constitutional (human) rights. Most notably, the Supreme Court of India has extracted a range of animal rights from the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act and, by reading them in the light of the Constitution, elevated those statutory rights to the status of fundamental rights. 8 Furthermore, courts in Argentina 9 and Colombia 10 have extended the fundamental right of habeas corpus , along with the underlying right to liberty, to captive animals. 11 These (so far isolated) acts of judicial recognition of animal rights may be read as early manifestations of an incipient formation of legal animal rights. Against this backdrop, there is a pressing practical need for legal animal rights theory, in order to explain and guide the as yet still nascent—and somewhat haphazard—evolution of legal animal rights.

This article seeks to take the first steps towards building a more systematic and nuanced theory of legal animal rights. Navigating the existing theoretical patchwork, the article revisits and connects relevant themes that have so far been addressed only in a scattered or cursory manner, and consolidates them into an overarching framework for legal animal rights. Moreover, tackling the well-known problem of ambiguity and obscurity involved in the generally vague, inconsistent and undifferentiated use of the umbrella term ‘animal rights’, this article brings analytical clarity into the debate by disentangling and unveiling different meanings and facets of legal animal rights. 12 To this end, the analysis identifies and separates three relevant sets of issues: (i) conceptual issues concerning the nature and foundations of legal animal rights, and, more generally, whether animals are the kind of beings who can potentially hold legal rights; (ii) doctrinal issues pertaining to existing animal welfare law and whether it confers some legal rights on animals—and, if so, what kind of rights; and (iii) normative issues as to why and what kind of legal rights animals ought ideally to have as a matter of future law. These thematic clusters will be addressed through three simple yet key questions: can , do and should animals have legal rights?

Section 2 will show that it is conceptually possible for animals to hold legal rights, and will clarify the formal structure and normative grounds of legal animal rights. Moreover, as section 3 will demonstrate, unwritten animal rights could arguably be extracted from existing animal welfare laws, even though such ‘animal welfare rights’ are currently imperfect and weak legal rights at best. In order to distinguish between these weak legal rights that animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law and the kind of strong legal rights that animals ought to have potentially or ideally, the new conceptual categories of ‘ simple animal rights’ and ‘ fundamental animal rights’ will be introduced. Finally, section 4 will explore a range of functional reasons why animals need such strong, fundamental rights as a matter of future law.

As a preliminary matter, it seems necessary to first address the conceptual issue whether animals potentially can have legal rights, irrespective of doctrinal and normative issues as to whether animals do in fact have, or should have, legal rights. Whether animals are possible or potential right holders—that is, the kind of beings to whom legal rights can be ascribed ‘without conceptual absurdity’ 13 —must be determined based on the general nature of rights, which is typically characterised in terms of the structure (or form) and grounds (or ultimate purpose) of rights. 14 Looking at the idea of animal rights through the lens of general rights theories helps clarify the conceptual foundations of legal animal rights by identifying their possible forms and grounds. The first subsection (A) focusses on two particular forms of conceptually basic rights—claims and liberties—and examines their structural compatibility with animal rights. The second subsection (B) considers the two main competing theories of rights—the will theory and interest theory—and whether, and on what grounds, they can accommodate animals as potential right holders.

A. The Structure of Legal Animal Rights

The formal structure of rights is generally explicated based on the Hohfeldian typology of rights. 15 Hohfeld famously noted that the generic term ‘right’ tends to be used indiscriminately to cover ‘any sort of legal advantage’, and distinguished four different types of conceptually basic rights: claims (rights stricto sensu ), liberties, powers and immunities. 16 In the following, I will show on the basis of first-order rights 17 —claims and liberties—that legal animal rights are structurally possible, and what such legal relations would consist of. 18

(i) Animal claim rights

To have a right in the strictest sense is ‘to have a claim to something and against someone’, the claim right necessarily corresponding with that person’s correlative duty towards the right holder to do or not to do something. 19 This type of right would take the form of animals holding a claim to something against, for example, humans or the state who bear correlative duties to refrain from or perform certain actions. Such legal animal rights could be either negative rights (correlative to negative duties) to non-interference or positive rights (correlative to positive duties) to the provision of some good or service. 20 The structure of claim rights seems especially suitable for animals, because these are passive rights that concern the conduct of others (the duty bearers) and are simply enjoyed rather than exercised by the right holder. 21 Claim rights would therefore assign to animals a purely passive position that is specified by the presence and performance of others’ duties towards animals, and would not require any actions by the animals themselves.

(ii) Animal liberties

Liberties, by contrast, are active rights that concern the right holder’s own conduct. A liberty to engage in or refrain from a certain action is one’s freedom of any contrary duty towards another to eschew or undertake that action, correlative to the no right of another. 22 On the face of it, the structure of liberties appears to lend itself to animal rights. A liberty right would indicate that an animal is free to engage in or avoid certain behaviours, in the sense of being free from a specific duty to do otherwise. Yet, an obvious objection is that animals are generally incapable of having any legal duties. 23 Given that animals are inevitably in a constant state of ‘no duty’ and thus ‘liberty’, 24 this seems to render the notion of liberty rights somewhat pointless and redundant in the case of animals, as it would do nothing more than affirm an already and invariably existing natural condition of dutylessness. However, this sort of ‘natural liberty’ is, in and of itself, only a naked liberty, one wholly unprotected against interferences by others. 25 That is, while animals may have the ‘natural liberty’ of, for example, freedom of movement in the sense of not having (and not being capable of having) a duty not to move around, others do not have a duty vis-à-vis the animals not to interfere with the exercise of this liberty by, for example, capturing and caging them.

The added value of turning the ‘natural liberties’ of animals into liberty rights thus lies in the act of transforming unprotected, naked liberties into protected, vested liberties that are shielded from certain modes of interference. Indeed, it seems sensible to think of ‘natural liberties’ as constituting legal rights only when embedded in a ‘protective perimeter’ of claim rights and correlative duties within which such liberties may meaningfully exist and be exercised. 26 This protective perimeter consists of some general duties (arising not from the liberty right itself, but from other claim rights, such as the right to life and physical integrity) not to engage in ‘at least the cruder forms of interference’, like physical assault or killing, which will preclude most forms of effective interference. 27 Moreover, liberties may be fortified by specific claim rights and correlative duties strictly designed to protect a particular liberty, such as if the state had a (negative) duty not to build highways that cut across wildlife habitat, or a (positive) duty to build wildlife corridors for such highways, in order to facilitate safe and effective freedom of movement for the animals who live in these fragmented habitats.

(iii) Animal rights and duties: correlativity and reciprocity

Lastly, some remarks on the relation between animal rights and duties seem in order. Some commentators hold that animals are unable to possess legal rights based on the influential idea that the capacity for holding rights is inextricably linked with the capacity for bearing duties. 28 Insofar as animals are not capable of bearing legal duties in any meaningful sense, it follows that animals cannot have legal (claim) rights against other animals, given that those other animals would be incapable of holding the correlative duties. But does this disqualify animals from having legal rights altogether, for instance, against legally competent humans or the state?

While duties are a key component of (first-order) rights—with claim rights necessarily implying the presence of a legal duty in others and liberties necessarily implying the absence of a legal duty in the right holder 29 —neither of them logically entails that the right holder bear duties herself . As Kramer aptly puts it:

Except in the very unusual circumstances where someone holds a right against himself, X’s possession of a legal right does not entail X’s bearing of a legal duty; rather, it entails the bearing of a legal duty by somebody else. 30

This underscores an important distinction between the conceptually axiomatic correlativity of rights and duties—the notion that every claim right necessarily implies a duty—and the idea of a reciprocity of rights and duties—the notion that (the capacity for) right holding is conditioned on (the capacity for) duty bearing. While correlativity refers to an existential nexus between a right and a duty held by separate persons within one and the same legal relation , reciprocity posits a normative nexus between the right holding and duty bearing of one and the same person within separate, logically unrelated legal relations.

The claim that the capacity for right holding is somehow contingent on the right holder’s (logically unrelated) capacity for duty bearing is thus, as Kramer puts it, ‘straightforwardly false’ from a Hohfeldian point of view. 31 Nevertheless, there may be other, normative reasons (notably underpinned by social contract theory) for asserting that the class of appropriate right holders should be limited to those entities that, in addition to being structurally possible right holders, are also capable of reciprocating, that is, of being their duty bearers’ duty bearers. 32 However, such a narrow contractarian framing of right holding should be rejected, not least because it misses the current legal reality. 33 With a view to legally incompetent humans (eg infants and the mentally incapacitated), contemporary legal systems have manifestly cut the connection between right holding and the capacity for duty bearing. 34 As Wenar notes, the ‘class of potential right holders has expanded to include duty-less entities’. 35 Similarly, it would be neither conceptually nor legally apposite to infer from the mere fact that animals do not belong to the class of possible duty bearers that they cannot belong to the class of possible right holders. 36

B. The Grounds of Legal Animal Rights

While Hohfeld’s analytical framework is useful to outline the possible forms and composition of legal animal rights, Kelch rightly points out that it remains agnostic as to the normative grounds of potential animal rights. 37 In this respect, the two dominant theories of rights advance vastly differing accounts of the ultimate purpose of rights and who can potentially have them. 38 Whereas the idea of animal rights does not resonate well with the will theory, the interest theory quite readily provides a conceptual home for it.

(i) Will theory

According to the will theory, the ultimate purpose of rights is to promote and protect some aspect of an individual’s autonomy and self-realisation. A legal right is essentially a ‘legally respected choice’, and the right holder a ‘small scale sovereign’ whose exercise of choice is facilitated by giving her discretionary ‘legal powers of control’ over others’ duties. 39 The class of potential right holders thus includes only those entities that possess agency and legal competence, which effectively rules out the possibility of animals as right holders, insofar as they lack the sort or degree of agency necessary for the will-theory conception of rights. 40

However, the fact that animals are not potential right holders under the will theory does not necessarily mean that animals cannot have legal rights altogether. The will theory has attracted abundant criticism for its under-inclusiveness as regards both the class of possible right holders 41 and the types of rights it can plausibly account for, and thus seems to advance too narrow a conception of rights for it to provide a theoretical foundation for all rights. 42 In particular, it may be noted that the kinds of rights typically contemplated as animal rights are precisely of the sort that generally exceed the explanatory power of the will theory, namely inalienable, 43 passive, 44 public-law 45 rights that protect basic aspects of animals’ (partially historically and socially mediated) vulnerable corporeal existence. 46 Such rights, then, are best explained on an interest-theoretical basis.

(ii) Interest theory

Animal rights theories most commonly ground animal rights in animal interests, and thus naturally gravitate to the interest theory of rights. 47 According to the interest theory, the ultimate purpose of rights is the protection and advancement of some aspect(s) of an individual’s well-being and interests. 48 Legal rights are essentially ‘legally-protected interests’ that are of special importance and concern. 49 With its emphasis on well-being rather than on agency, the interest theory seems more open to the possibility of animal rights from the outset. Indeed, as regards the class of possible right holders, the interest theory does little conceptual filtering beyond requiring that right holders be capable of having interests. 50 Given that, depending on the underlying definition of ‘interest’, this may cover all animals, plants and, according to some, even inanimate objects, the fairly modest and potentially over-inclusive conceptual criterion of ‘having interests’ is typically complemented by the additional, more restrictive moral criterion of ‘having moral status’. 51 Pursuant to this limitation, not just any being capable of having interests can have rights, but only those whose well-being is not merely of instrumental, but of intrinsic or ‘ultimate value’. 52

Accordingly, under the interest theory, two conditions must be met for animals to qualify as potential right holders: (i) animals must have interests, (ii) the protection of which is required not merely for ulterior reasons, but for the animals’ own sake, because their well-being is intrinsically valuable. Now, whether animals are capable of having interests in the sense relevant to having rights and whether they have moral status in the sense of inherent or ultimate value is still subject to debate. For example, some have denied that animals possess interests based on an understanding of interests as wants and desires that require complex cognitive abilities such as having beliefs and language. 53 However, most interest theories opt for a broader understanding of interests in the sense of ‘being in someone’s interest’, meaning that an interest holder can be ‘made better or worse off’ and is able to benefit in some way from protective action. 54 Typically, though not invariably, the capacity for having interests in this broad sense is bound up with sentience—the capacity for conscious and subjective experiences of pain, suffering and pleasure. 55 Thus, most interest theorists quite readily accept (sentient) animals as potential right holders, that is, as the kind of beings that are capable of holding legal rights. 56

More importantly yet for legal purposes, the law already firmly rests on the recognition of (some) animals as beings who possess intrinsically valuable interests. Modern animal welfare legislation cannot be intelligibly explained other than as acknowledging that the animals it protects (i) have morally and legally relevant goods and interests, notably in their welfare, life and physical or mental integrity. 57 Moreover, it rests on an (implicit or explicit) recognition of those animals as (ii) having moral status in the sense of having intrinsic value. The underlying rationale of modern, non-anthropocentric, ethically motivated animal protection laws is the protection of animals qua animals, for their own sake, rather than for instrumental reasons. 58 Some laws go even further by directly referencing the ‘dignity’ or ‘intrinsic value’ of animals. 59

It follows that existing animal welfare laws already treat animals as intrinsically valuable holders of some legally relevant interests—and thus as precisely the sorts of beings who possess the qualities that are, under an interest theory of rights, necessary and sufficient for having rights. This, then, prompts the question whether those very laws do not only conceptually allow for potential animal rights, but might also give rise to actual legal rights for animals.

Notwithstanding that animals could have legal rights conceptually, the predominant doctrinal opinion is that, as a matter of positive law, animals do not have any, at least not in the sense of proper, legally recognised and claimable rights. 60 Yet, there is a certain inclination, especially in Anglo-American parlance, to speak—in a rather vague manner—of ‘animal rights’ as if they already exist under current animal welfare legislation. Such talk of existing animal rights is, however, rarely backed up with further substantiations of the underlying claim that animal welfare laws do in fact confer legal rights on animals. In the following, I will examine whether animals’ existing legal protections may be classified as legal rights and, if so, what kind of rights these constitute. The analysis will show (A) that implicit animal rights (hereinafter referred to as ‘animal welfare rights’) 61 can be extracted from animal welfare laws as correlatives of explicit animal welfare duties, but that this reading remains largely theoretical so far, given that such unwritten animal rights are hardly legally recognised in practice. Moreover, (B) the kind of rights derivable from animal welfare laws are currently at best imperfect and weak rights that do not provide animals with the sort of robust normative protection that is generally associated with legal rights, and typically also expected from legal animal rights qua institutionalised moral animal rights. Finally, (C) the new conceptual categories of ‘ simple animal rights’ and ‘ fundamental animal rights’ are introduced in order to distinguish, and account for the qualitative differences, between such current, imperfect, weak animal rights and potential, ideal, strong animal rights.

A. Extracting ‘Animal Welfare Rights’ from Animal Welfare Laws

(i) the simple argument from correlativity.

Existing animal welfare laws are not framed in the language of rights and do not codify any explicit animal rights. They do, however, impose on people legal duties designed to protect animals—duties that demand some behaviour that is beneficial to the welfare of animals. Some commentators contend that correlative (claim) rights are thereby conferred upon animals as the beneficiaries of such duties. 62 This view is consistent with, and, indeed, the logical conclusion of, an interest-theoretical analysis. 63 Recall that rights are essentially legally protected interests of intrinsically valuable individuals, and that a claim right is the ‘position of normative protectedness that consists in being owed a … legal duty’. 64 Under existing animal welfare laws, some goods of animals are legally protected interests in exactly this sense of ultimately valuable interests that are protected through the imposition of duties on others. However, the inference from existing animal welfare duties to the existence of correlative ‘animal welfare rights’ appears to rely on a somewhat simplistic notion of correlativity, along the lines of ‘where there is a duty there is a right’. 65 Two objections in particular may be raised against the view that beneficial duties imposed by animal welfare laws are sufficient for creating corresponding legal rights in animals.

First, not every kind of duty entails a correlative right. 66 While some duties are of an unspecific and general nature, only relational, directed duties which are owed to rather than merely regarding someone are the correlatives of (claim) rights. Closely related, not everyone who stands to benefit from the performance of another’s duty has a correlative right. According to a standard delimiting criterion, beneficial duties generate rights only in the intended beneficiaries of such duties, that is, those who are supposed to benefit from duties designed to protect their interests. 67 Yet, animal welfare duties, in a contemporary reading, are predominantly understood not as indirect duties regarding animals—duties imposed to protect, for example, an owner’s interest in her animal, public sensibilities or the moral character of humans—but as direct duties owed to the protected animals themselves. 68 Moreover, the constitutive purpose of modern animal welfare laws is to protect animals for their own sake. Animals are therefore clearly beneficiaries in a qualified sense, that is, they are not merely accidental or incidental, but the direct and intended primary beneficiaries of animal welfare duties. 69

Secondly, one may object that an analysis of animal rights as originating from intentionally beneficial duties rests on a conception of rights precisely of the sort which has the stigma of redundancy attached to it. Drawing on Hart, this would appear to cast rights as mere ‘alternative formulation of duties’ and thus ‘no more than a redundant translation of duties … into a terminology of rights’. 70 Admittedly, as MacCormick aptly puts it:

[To] rest an account of claim rights solely on the notion that they exist whenever a legal duty is imposed by a law intended to benefit assignable individuals … is to treat rights as being simply the ‘reflex’ of logically prior duties. 71

One way of responding to this redundancy problem is to reverse the logical order of rights and duties. On this account, rights are not simply created by (and thus logically posterior to) beneficial duties, but rather the converse: such duties are derived from and generated by (logically antecedent) rights. For example, according to Raz, ‘Rights are grounds of duties in others’ and thus justificationally prior to duties. 72 However, if rights are understood not just as existentially correlative, but as justificationally prior to duties, identifying intentionally beneficial animal welfare duties as the source of (logically posterior) animal rights will not suffice. In order to accommodate the view that rights are grounds of duties, the aforementioned argument from correlativity needs to be reconsidered and refined.

(ii) A qualified argument from correlativity

A refined, and reversed, argument from correlativity must show that animal rights are not merely reflexes created by animal welfare duties, but rather the grounds for such duties. In other words, positive animal welfare duties must be plausibly explained as some kind of codified reflection, or visible manifestation, of ‘invisible’ background animal rights that give rise to those duties.

This requires further clarification of the notion of a justificational priority of rights over duties. On the face of it, the idea that rights are somehow antecedent to duties appears to be at odds with the Hohfeldian correlativity axiom, which stipulates an existential nexus of mutual entailment between rights and duties—one cannot exist without the other. 73 Viewed in this light, it seems paradoxical to suggest that rights are causal for the very duties that are simultaneously constitutive of those rights—cause and effect seem to be mutually dependent. Gewirth offers a plausible explanation for this seemingly circular understanding of the relation between rights and duties. He illustrates that the ‘priority of claim rights over duties in the order of justifying purpose or final causality is not antithetical to their being correlative to each other’ by means of an analogy:

Parents are prior to their children in the order of efficient causality, yet the (past or present) existence of parents can be inferred from the existence of children, as well as conversely. Hence, the causal priority of parents to children is compatible with the two groups’ being causally as well as conceptually correlative. The case is similar with rights and duties, except that the ordering relation between them is one of final rather than efficient causality, of justifying purpose rather than bringing-into-existence. 74

Upon closer examination, this point may be specified even further. To stay with the analogy of (biological) 75 parents and their children: it is actually the content of ‘parents’—a male and a female (who at some point procreate together)—that exists prior to and independently of possibly ensuing ‘children’, whereas this content turns into ‘parents’ only in conjunction with ‘children’. That is, the concepts of ‘parents’ and ‘children’ are mutually entailing, whilst, strictly speaking, it is not ‘parents’, but rather that which will later be called ‘parents’ only once the ‘child’ comes into existence—the pre-existing content—which is antecedent to and causal for ‘children’.

Applied to the issue of rights and duties, this means that it is actually the content of a ‘right’—an interest—that exists prior to and independently of, and is (justificationally) causal for the creation of, a ‘duty’, which, in turn, is constitutive of a ‘right’. The distinction between ‘right’ and its content—an interest—allows the pinpointing of the latter as the reason for, and the former as the concomitant correlative of, a duty imposed to protect the pre-existing interest. It may thus be restated, more precisely, that it is not rights, but the protected interests which are grounds of duties. Incidentally, this specification is consistent with Raz’s definition of rights, according to which ‘having a right’ means that an aspect of the right holder’s well-being (her interest) ‘is a sufficient reason for holding some other person(s) to be under a duty’. 76 Now, the enactment of modern animal welfare laws is in and of itself evidence of the fact that some aspects of animals’ well-being (their interests) are—both temporally and justificationally—causal and a sufficient reason for imposing duties on others. Put differently: animal interests are grounds of animal welfare duties , and this, in turn, is conceptually constitutive of animal rights .

In conclusion, existing animal welfare laws could indeed be analysed as comprising unwritten ‘animal welfare rights’ as implicit correlatives of the explicit animal welfare duties imposed on others. The essential feature of legal rules conferring rights is that they specifically aim at protecting individual interests or goods—whether they do so expressis verbis or not is irrelevant. 77 Even so, in order for a right to be an actual (rather than a potential or merely postulated) legal right, it should at least be legally recognised (if not claimable and enforceable), 78 which is determined by the applicable legal rules. In the absence of unequivocal wording, whether a legal norm confers unwritten rights on animals becomes a matter of legal interpretation. While theorists can show that a rights-based approach lies within the bounds of a justifiable interpretation of the law, an actual, valid legal right hardly comes to exist by the mere fact that some theorists claim it exists. For that to happen, it seems instrumental that some public authoritative body, notably a court, recognises it as such. That is, while animals’ existing legal protections may already provide for all the ingredients constitutive of rights, it takes a court to actualise this potential , by authoritatively interpreting those legal rules as constituting rights of animals. However, because courts, with a few exceptions, have not done so thus far, it seems fair to say that unwritten animal rights are not (yet) legally recognised in practice and remain a mostly theoretical possibility for now. 79

B. The Weakness of Current ‘Animal Welfare Rights’

Besides the formal issue of legal recognition, there are substantive reasons for questioning whether the kind of rights extractable from animal welfare laws are really rights at all. This is because current ‘animal welfare rights’ are unusually weak rights that do not afford the sort of strong normative protection that is ordinarily associated with legal rights. 80 Classifying animals’ existing legal protections as ‘rights’ may thus conflict with the deeply held view that, because they protect interests of special importance, legal rights carry special normative force . 81 This quality is expressed in metaphors of rights as ‘trumps’, 82 ‘protective fences’, 83 protective shields or ‘No Trespassing’ signs, 84 or ‘suits of armor’. 85 Rights bestow upon individuals and their important interests a particularly robust kind of legal protection against conflicting individual or collective interests, by singling out ‘those interests that are not to be sacrificed to the utilitarian calculus ’ and ‘whose promotion or protection is to be given qualitative precedence over the social calculus of interests generally’. 86 Current ‘animal welfare rights’, by contrast, provide an atypically weak form of legal protection, notably for two reasons: because they protect interests of secondary importance or because they are easily overridden.

In order to illustrate this, consider the kind of rights that can be extracted from current animal welfare laws. Given that these are the correlatives of existing animal welfare duties, the substance of these rights must mirror the content laid down in the respective legal norms. This extraction method produces, first, a rather odd subgroup of ‘animal welfare rights’ that have a narrow substantive scope protecting highly specific, secondary interests, such as a (relative) right to be slaughtered with prior stunning, 87 an (absolute) right that experiments involving ‘serious injuries that may cause severe pain shall not be carried out without anaesthesia’ 88 or a right of chicks to be killed by fast-acting methods, such as homogenisation or gassing, and to not be stacked on top of each other. 89 The weak and subsidiary character of such rights becomes clearer when placed within the permissive institutional context in which they operate, and when taking into account the more basic interests that are left unprotected. 90 While these rights may protect certain secondary, derivative interests (such as the interest in being killed in a painless manner ), they are simultaneously premised on the permissibility of harming the more primary interests at stake (such as the interest in not being killed at all). Juxtaposed with the preponderance of suffering and killing that is legally allowed in the first place, phrasing the residual legal protections that animals do receive as ‘rights’ may strike us as misleading. 91

But then there is a second subgroup of ‘animal welfare rights’, extractable from general animal welfare provisions, that have a broader scope, protecting more basic, primary interests, such as a right to well-being, life, 92 dignity, 93 to not suffer unnecessarily, 94 or against torture and cruel treatment. 95 Although the object of such rights is of a more fundamental nature, the substantive guarantee of these facially fundamental rights is, to a great extent, eroded by a conspicuously low threshold for permissible infringements. 96 That is, these rights suffer from a lack of normative force, which manifests in their characteristically high infringeability (ie their low resistance to being overridden). Certainly, most rights (whether human or animal) are relative prima facie rights that allow for being balanced against conflicting interests and whose infringement constitutes a violation only when it is not justified, notably in terms of necessity and proportionality. 97 Taking rights seriously does, however, require certain safeguards ensuring that rights are only overridden by sufficiently important considerations whose weight is proportionate to the interests at stake. As pointed out by Waldron, the idea of rights is seized on as a way of resisting, or at least restricting, the sorts of trade-offs that would be acceptable in an unqualified utilitarian calculus, where ‘important individual interests may end up being traded off against considerations which are intrinsically less important’. 98 Yet, this is precisely what happens to animals’ prima facie protected interests, any of which—irrespective of how important or fundamental they are—may enter the utilitarian calculus, where they typically end up being outweighed by human interests that are comparatively less important or even trivial, notably dietary and fashion preferences, economic profitability, recreation or virtually any other conceivable human interest. 99

Any ‘animal welfare rights’ that animals may presently be said to have are thus either of the substantively oddly specific, yet rather secondary, kind or, in the case of more fundamental prima facie rights, such that are highly infringeable and ‘evaporate in the face of consequential considerations’. 100 The remaining question is whether these features render animals’ existing legal protections non-rights or just particularly unfit or weak rights , but rights nonetheless. The answer will depend on whether the quality of special strength, weight or force is considered a conceptually constitutive or merely typical but not essential feature of rights. On the first view, a certain normative force would function as a threshold criterion for determining what counts as a right and for disqualifying those legal protections that may structurally resemble rights but do not meet a minimum weight. 101 On the second view, the normative force of rights would serve as a variable that defines the particular weight of different types of rights on a spectrum from weak to strong. 102 To illustrate the intricacies of drawing a clear line between paradigmatically strong rights, weak rights or non-rights based on this criterion, let us return to the analogy with (biological) ‘parents’. In a minimal sense, the concept of ‘parents’ may be essentially defined as ‘biological creators of a child’. Typically, however, a special role as nurturer and caregiver is associated with the concept of ‘parent’. Now, is someone who merely meets the minimal conceptual criterion (by being the biological creator), but not the basic functions attached to the concept (by not giving care), still a ‘parent’? And, if so, to what extent? Are they a full and proper ‘parent’, or merely an imperfect, dysfunctional form of ‘parent’, a bad ‘parent’, but a ‘parent’ nonetheless? Maybe current animal rights are ‘rights’ in a similar sense as an absent, negligent, indifferent biological mother or father who does not assume the role and responsibilities that go along with parenthood is still a ‘parent’. That is, animals’ current legal protections may meet the minimal conceptual criteria for rights, but they do not perform the characteristic normative function of rights. They are, therefore, at best atypically weak and imperfect rights.

C. The Distinction between Simple and Fundamental Animal Rights

In the light of the aforesaid, if one adopts the view that animals’ existing legal protections constitute legal rights—that is, if one concludes that existing animal welfare laws confer legal rights on animals despite a lack of explicit legal enactment or of any coherent judicial recognition of unwritten animal rights, and that the kind of rights extractable from animal welfare law retain their rights character regardless of how weak they are—then an important qualification needs to be made regarding the nature and limits of such ‘animal welfare rights’. In particular, it must be emphasised that this type of legal animal rights falls short of (i) our ordinary understanding of legal rights as particularly robust protections of important interests and (ii) institutionalising the sort of inviolable, basic moral animal rights (along the lines of human rights) that animal rights theorists typically envisage. 103 It thus seems warranted to separate the kind of imperfect and weak legal rights that animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law from the kind of ideal, 104 proper, strong fundamental rights that animals potentially ought to have as a matter of future law.

In order to denote and account for the qualitative difference between these two types of legal animal rights, and drawing on similar distinctions as regards the rights of individuals under public and international law, 105 I propose to use the conceptual categories of fundamental animal rights and other, simple animal rights. As to the demarcating criteria, we can distinguish between simple and fundamental animal rights based on a combination of two factors: (i) substance (fundamentality or non-fundamentality of the protected interests) and (ii) normative force (degree of infringeability). Accordingly, simple animal rights can be defined as weak legal rights whose substantive content is of a non-fundamental, ancillary character and/or that lack normative force due to their high infringeability. In contradistinction, fundamental animal rights are strong legal rights along the lines of human rights that are characterised by the cumulative features of substantive fundamentality and normative robustness due to their reduced infringeability.

The ‘animal welfare rights’ derivable from current animal welfare laws are simple animal rights. However, it is worth noting that while the first subtype of substantively non-fundamental ‘animal welfare rights’ belongs to this category irrespective of their infringeability, 106 the second subtype of substantively fundamental ‘animal welfare rights’ presently falls in this category purely in respect of their characteristically high infringeability. Yet, the latter is a dynamic and changeable feature, insofar as these rights could be dealt with, in case of conflict, in a manner whereby they would prove to be more robust. In other words, while the simple animal rights of the second subtype currently lack the normative force of legal rights, they do have the potential to become fundamental animal rights. Why animals need such fundamental rights will be explored in the final section.

Beyond the imperfect, weak, simple rights that animals may be said to have based on existing animal welfare laws, a final normative question remains with a view to the future law: whether animals ought to have strong legal rights proper. I will focus on fundamental animal rights—such as the right to life, bodily integrity, liberty and freedom from torture—as these correspond best with the kind of ‘ought to be legal rights’ typically alluded to in animal rights discourse. Given the general appeal of rights language, it is not surprising that among animal advocates there is an overall presumption in favour of basic human rights-like animal rights. 107 However, it is often simply assumed that, rather than elucidated why, legal rights would benefit animals and how this would strengthen their protection. In order to undergird the normative claim that animals should have strong legal rights, the following subsections will look at functional reasons why animals need such rights. 108 I will do so through a non-exhaustive exploration of the potential legal advantages and political utility of fundamental animal rights over animals’ current legal protections (be they animal welfare laws or ‘animal welfare rights’).

A. Procedural Aspect: Standing and Enforceability

Against the backdrop of today’s well-established ‘enforcement gap’ and ‘standing dilemma’, 109 one of the most practical benefits typically associated with, or expected from, legal animal rights is the facilitation of standing for animals in their own right and, closely related, the availability of more efficient mechanisms for the judicial enforcement of animals’ legal protections. 110 This is because legal rights usually include the procedural element of having standing to sue, the right to seek redress and powers of enforcement—which would enable animals (represented by legal guardians) to institute legal proceedings in their own right and to assert injuries of their own. 111 This would also ‘decentralise’ enforcement, that is, it would not be concentrated in the hands (and at the sole discretion) of public authorities, but supplemented by private standing of animals to demand enforcement. Ultimately, such an expanded enforceability could also facilitate incremental legal change by feeding animal rights questions into courts as fora for public deliberation.

However, while standing and enforceability constitute crucial procedural components of any effective legal protection of animals, for present purposes, it should be noted that fundamental animal rights (or any legal animal rights) are—albeit maybe conducive—neither necessary nor sufficient to this end. On the one hand, not all legal rights (eg some socio-economic human rights) are necessarily enforceable. Merely conferring legal rights on animals will therefore, in itself, not guarantee sufficient legal protection from a procedural point of view. Rather, fundamental animal rights must encompass certain procedural rights, such as the right to access to justice, in order to make them effectively enforceable. On the other hand, animals or designated animal advocates could simply be granted standing auxiliary to today’s animal welfare laws, which would certainly contribute towards narrowing the enforcement gap. 112 Yet, standing as such merely offers the purely procedural benefit of being able to legally assert and effectively enforce any given legal protections that animals may have, but has no bearing on the substantive content of those enforceable protections. Given that the issue is not just one of improving the enforcement of animals’ existing legal protections, but also of substantially improving them, standing alone cannot substitute for strong substantive animal rights. Therefore, animals will ultimately need both strong substantive and enforceable rights, which may be best achieved through an interplay of fundamental rights and accompanying procedural guarantees.

B. Substantive Aspect: Stronger Legal Protection for Important Interests

The aforesaid suggests that the critical function of fundamental animal rights is not procedural in nature; rather, it is to substantively improve and fortify the protection of important animal interests. In particular, fundamental animal rights would strengthen the legal protection of animals on three levels: by establishing an abstract equality of arms, by broadening the scope of protection to include more fundamental substantive guarantees and by raising the burden of justification for infringements.

First of all, fundamental animal rights would create the structural preconditions for a level playing field where human and animal interests are both reinforced by equivalent rights, and can thus collide on equal terms. Generally speaking, not all legally recognised interests count equally when balanced against each other, and rights-empowered interests typically take precedence over or are accorded more weight than unqualified competing interests. 113 At present, the structural makeup of the balancing process governing human–animal conflicts is predisposed towards a prioritisation of human over animal interests. Whereas human interests are buttressed by strong, often fundamental rights (such as economic, religious or property rights), the interests at stake on the animal side, if legally protected at all, enter the utilitarian calculus as unqualified interests that are merely shielded by simple animal welfare laws, or simple rights that evaporate quickly in situations of conflict and do not compare to the sorts of strong rights that reinforce contrary human interests. 114 In order to achieve some form of abstract equality of arms, animals’ interests need to be shielded by strong legal rights that are a match to humans’ rights. Fundamental animal rights would correct this structural imbalance and set the stage for an equal consideration of interests that is not a priori biased in favour of humans’ rights.

Furthermore, as defined above, fundamental animal rights are characterised by both their substantive fundamentality and normative force, and would thus strengthen animals’ legal protection in two crucial respects. On a substantive level , fundamental animal rights are grounded in especially important, fundamental interests. Compared to substantively non-fundamental simple animal rights, which provide for narrow substantive guarantees that protect secondary interests, fundamental animal rights would expand the scope of protection to cover a wider array of basic and primary interests. As a result, harming fundamentally important interests of animals—while readily permissible today insofar as such interests are often not legally protected in the first place 115 —would trigger a justification requirement that initially allows those animal interests to enter into a balancing process. For even with fundamental animal rights in play, conflicts between human and animal interests will inevitably continue to exist—albeit at the elevated and abstractly equal level of conflicts of rights—and therefore require some sort of balancing mechanism. 116

On this justificatory level , fundamental animal rights would then demand a special kind and higher burden of justification for infringements. 117 As demonstrated above, substantively fundamental yet highly infringeable simple animal rights are marked by a conspicuously low threshold for justifiable infringements, and are regularly outweighed by inferior or even trivial human interests. By contrast, the normative force of fundamental animal rights rests on their ability to raise the ‘level of the minimally sufficient justification’. 118 Modelling these more stringent justification requirements on established principles of fundamental (human) rights adjudication, this would, first, limit the sorts of considerations that constitute a ‘legitimate aim’ which can be balanced against fundamental animal rights. Furthermore, the balancing process must encompass a strict proportionality analysis, comprised of the elements of suitability, necessity and proportionality stricto sensu , which would preclude the bulk of the sorts of low-level justifications that are currently sufficient. 119 This heightened threshold for justifiable infringements, in turn, translates into a decreased infringeability of fundamental animal rights and an increased immunisation of animals’ prima facie protected interests against being overridden by conflicting considerations and interests of lesser importance.

Overall, considering this three-layered strengthening of the legal protection of animals’ important interests, fundamental animal rights are likely to set robust limits to the violability and disposability of animals as means to human ends, and to insulate animals from many of the unnecessary and disproportionate inflictions of harm that are presently allowed by law.

C. Fallback Function: The Role of Rights in Non-ideal Societies

Because contemporary human–animal interactions are, for the most part, detrimental to animals, the latter appear to be in particular need of robust legal protections against humans and society. 120 Legal rights, as strong (but not impenetrable) shields, provide an instrument well suited for this task, as they operate in a way that singles out and protects important individual goods against others and the political community as a whole. For this reason, rights are generally considered an important counter-majoritarian institution, but have also been criticised for their overly individualistic, antagonistic and anti-communitarian framing. 121 Certainly, it may be debated whether there is a place for the institution of rights in an ideal society—after all, rights are not decrees of nature, but human inventions that are historically and socially contingent. 122 However, rights are often born from imperfect social conditions, as a ‘response to a failure of social responsibility’ 123 and as corrections of experiences of injustice, or, as Dershowitz puts it: ‘ rights come from wrongs ’. 124 Historical experience suggests that, at least in non-ideal societies, there is a practical need for rights as a safety net—a ‘position of fall-back and security’ 125 —that guarantees individuals a minimum degree of protection, in case or because other, less coercive social or moral mechanisms fail to do so.

Yet, as Edmundson rightly points out, this view of rights as backup guarantees does not quite capture the particular need for rights in the case of animals. 126 It is premised on the existence of a functioning overall social structure that can in some cases, and maybe in the ideal case, substitute for rights. However, unlike many humans, most animals are not embedded in a web of caring, affectionate, benevolent relations with humans to begin with, but rather are caught up in a system of exploitative, instrumental and harmful relations. For the vast majority of animals, it is not enough to say that rights would serve them as fallbacks, because there is nowhere to fall from—by default, animals are already at (or near) the bottom. Accordingly, the concrete need for rights may be more acute in the case of animals, as their function is not merely to complement, but rather to compensate for social and moral responsibility, which is lacking in the first place. 127 To give a (somewhat exaggerated) example: from the perspective of a critical legal scholar, meta-theorising from his office in the ivory tower, it may seem easier, and even desirable, to intellectually dispense with the abstract notion of rights, whereas for an elephant who is actually hunted down for his ivory tusks, concrete rights may make a very real difference, literally between life and death. Therefore, under the prevailing social conditions, animals need a set of basic rights as a primary ‘pull-up’ rather than as a subsidiary backup—that is, as compensatory baseline guarantees rather than as complementary background guarantees.

D. Transformative Function: Rights as ‘Bridges’ between Non-ideal Realities and Normative Ideals

Notwithstanding that animals need fundamental rights, we should not fail to recognise that even the minimum standards such rights are designed to establish and safeguard seem highly ambitious and hardly politically feasible at present. Even a rudimentary protection of fundamental animal rights would require far-ranging changes in our treatment of animals, and may ultimately rule out ‘virtually all existing practices of the animal-use industries’. 128 Considering how deeply the instrumental and inherently harmful use of animals is woven into the economic and cultural fabric of contemporary societies, and how pervasive animal cruelty is on both an individual and a collective level, the implications of fundamental animal rights indeed seem far removed from present social practices. 129 This chasm between normative aspirations and the deeply imperfect empirical realities they collide with is not, however, a problem unique to fundamental animal rights; rather, it is generally in the nature of fundamental rights—human or animal—to postulate normative goals that remain, to some extent, aspirational and unattainable. 130 Aspirational rights express commitments to ideals that, even if they may not be fully realisable at the time of their formal recognition, act as a continuous reminder and impulse that stimulates social and legal change towards a more expansive implementation. 131 In a similar vein, Bilchitz understands fundamental rights as moral ideals that create the pressure for legal institutionalisation and as ‘bridging concepts’ that facilitate the transition from past and present imperfect social realities towards more just societies. 132

This, then, provides a useful lens for thinking about the aspirational nature and transformative function of fundamental animal rights. Surely, the mere formal recognition of fundamental animal rights will not, by any realistic measure, bring about an instant practical achievement of the ultimate goal of ‘abolishing exploitation and liberating animals from enslavement’. 133 They do, however, create the legal infrastructure for moving from a non-ideal reality towards more ideal social conditions in which animal rights can be respected. For example, a strong animal right to life would (at least in industrialised societies) preclude most forms of killing animals for food, and would thus certainly conflict with the entrenched practice of eating meat. Yet, while the current social normality of eating animals may make an immediate prohibition of meat production and consumption unrealistic, it is also precisely the reason why animals need a right to life (ie a right not to be eaten), as fundamental rights help to denormalise (formerly) accepted social practices and to establish, internalise and habituate normative boundaries. 134 Moreover, due to their dynamic nature, fundamental rights can generate successive waves of more stringent and expansive duties over time. 135 Drawing on Bilchitz, the established concept of ‘progressive realisation’ (originally developed in the context of socio-economic human rights) may offer a helpful legal framework for the gradual practical implementation of animal rights. Accordingly, each fundamental animal right could be seen as comprising a minimum core that has to be ensured immediately, coupled with a general prohibition of retrogressive measures , and an obligation to progressively move towards a fuller realisation . 136 Therefore, even if fundamental animal rights may currently not be fully realisable, the very act of introducing them into law and committing to them as normative ideals places animals on the ‘legal map’ 137 and will provide a powerful generative basis—a starting point rather than an endpoint 138 —from which a dynamic process towards their more expansive realisation can unfold.

The question of animal rights has been of long-standing moral concern. More recently, the matter of institutionalising moral animal rights has come to the fore, and attaining legal rights for animals has become an important practical goal of animal advocates. This article started out from the prefatory observation that the process of juridification may already be in its early stages, as judicially recognised animal rights are beginning to emerge from both animal welfare law and human rights law. With legal animal rights on the horizon, the analysis set out to systematically address the arising conceptual, doctrinal and normative issues, in order to provide a theoretical underpinning for this legal development. The article showed that the idea of legal animal rights has a sound basis in both legal theory as well as in existing law. That is, legal animal rights are both conceptually possible and already derivable from current animal welfare laws. However, the analysis has also revealed that the ‘animal welfare rights’ which animals may be said to have as a matter of positive law fall short of providing the sort of strong normative protection that is typically associated with legal rights and that is furthermore expected from legal animal rights qua institutionalised moral animal rights. This discrepancy gave rise to a new conceptual distinction between two types of legal animal rights: simple and fundamental animal rights.

While the umbrella term ‘animal rights’ is often used loosely to refer to a wide range of legal protections that the law may grant to animals, distinguishing between simple and fundamental animal rights helps to unveil important differences between what we may currently call ‘legal animal rights’ based on existing animal welfare laws, which are weak legal rights at best, and the kind of strong, fundamental legal rights that animals should have as a matter of future law. This distinction is further conducive to curbing the trivialisation of the language of animal rights, as it allows us to preserve the normative force of fundamental animal rights by separating out weaker rights and classifying them as other, simple animal rights. Lastly, it is interesting to note that, with courts deriving legal animal rights from both animal welfare law and from constitutional, fundamental or human rights law, first prototypes of simple and fundamental animal rights are already discernible in emerging case law. Whereas Christopher Stone once noted that ‘each successive extension of rights to some new entity has been … a bit unthinkable’ throughout legal history, 139 the findings of this article suggest that we may presently be witnessing a new generation of legal rights in the making—legal animal rights, simple and fundamental.